When she was an 11-year-old schoolgirl, the writer Gitta Sereny passed through Nuremburg while a Nazi rally was in full swing. She recalled being awed by ‘the joyful faces all around, the rhythm of the sounds, the solemnity of the silences, the colours of the flags, the magic of the lights’. She understood nothing of the political message. Nor, of course, could she have known where it would all lead. It was pure showbusiness.

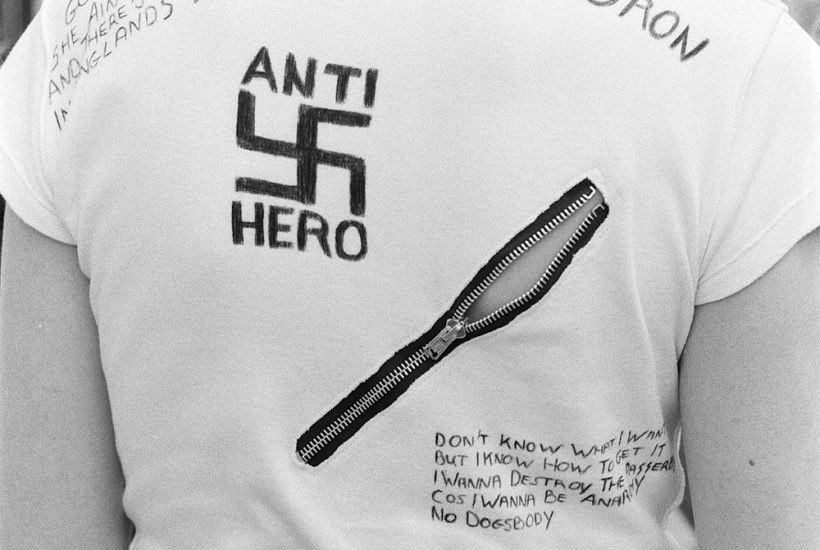

Reading her words in Daniel Rachel’s survey of certain musicians’ thorny fascination with the iconography of the Third Reich, two thoughts occur. One: it is no wonder that as early as the 1950s, rock’n’roll shows reminded some observers of Nuremburg. Two: most of the artists who toyed with iron crosses and swastikas, or lifted images from Triumph of the Will, thought no more deeply about it than that 11-year-old. Can they be so easily excused?

The author of three excellent oral histories, Rachel has produced not so much a narrative as a charge sheet. Having combed the music press archives for evidence of Nazi chic, he presents his findings with prosecutorial rigour, starkly juxtaposing them with capsule accounts of what the Nazis actually did. Damningly, the only people who agreed to be interviewed were those, like the journalist Vivien Goldman and the Clash’s manager Bernie Rhodes, who were critical at the time. The transgressors would rather pretend it never happened.

The list is much longer than you might think, reaching critical mass in the turbulent murk of the 1970s. Lemmy from Mötörhead famously collected Nazi memorabilia, but so too did members of the Animals, the Stooges, the Ramones, the Eagles and the Rolling Stones. Stevie Priest, bassist with glam-rockers the Sweet, sported an SS tunic and swastika armband on the Christmas 1974 edition of Top of the Pops. Ace Frehley, Kiss’s German-American guitarist, allegedly told the band’s two Jewish members: ‘The K-I stands for you two kikes and the S-S stands for my heritage.’ When challenged, the artists’ excuses were invariably feeble. ‘All the people who tell me not to wear swastikas, well they’re fascists,’ Wattie from the Exploited complained with boneheaded adolescent logic. Lemmy maintained that his collection was ‘a safety valve to stop that form of government ever existing again’, as if it were his selfless gift to democracy.

That these instances were crass and regrettable goes without saying. The puzzle is why, with a few hair-raising exceptions, they didn’t tip into anti-Semitism, racism or support for the contemporary far right. Many of these people had Jewish managers and bandmates, or were Jewish themselves, like Malcolm McLaren, the impresario who was most responsible for punk’s swastika fetish. Quite a few played benefit gigs for Rock Against Racism, music’s riposte to the National Front. The singer of the Angelic Upstarts even managed to wear both a swastika armband and a ‘Fascism Kills’ T-shirt in the same year. So what was going on?

Anti-Semitism was the central fact of Nazism, but, as Rachel points out, during the 1970s the swastika was more likely to evoke war movies than the Holocaust. David Bowie, half-mad from fame, cocaine and malnutrition, obsessed with political crisis and the mystique of power, made some of the most alarming proclamations (‘I believe Britain could benefit from a fascist leader’) but also the most unqualified apologies. His Führer babble was a thought experiment that got out of hand.

Most of Bowie’s peers barely thought at all. The use of Nazi tropes usually signified nothing more than what the critic Lester Bangs called ‘cheap nihilism’ – trolling the Greatest Generation by breaking the most obvious taboo. ‘It was always very much an anti-mums-and-dads thing,’ admits Siouxsie Sioux. There was also the glamour of evil, like heavy metal bands with Satan. Punks weren’t dressing like Mussolini or Franco.

It was, then, almost always a question of schoolboy amorality rather than political extremism. Fascinating sections on the influence of Leni Riefenstahl and the 1974 movie The Night Porter explain how unnervingly easy it was to detach the insignia from the doctrine and the aesthetic from the history. Many a rock star defended their Nazi cosplay by protesting that the uniforms looked ‘cool’. They were playing around with semiotic dynamite on the assumption that it wouldn’t explode.

Despite his author’s note (‘Any moral judgment is ultimately left to the discretion of the reader’), Rachel is understandably tough on these glib provocations. His serious, relentless book makes for especially uncomfortable reading at a time when smirking Nazi fandom is ripping through US politics like a virus and the taboos that the punks so carelessly poked seem both more necessary and more fragile than ever. Rachel’s account reaches its grotesque nadir with Kanye West selling swastika T-shirts and releasing a song called ‘Heil Hitler’. Not much irony or ambiguity to be found there. We may look down on the moral murk of the past but it took until last year for a major star to come out and tweet without equivocation: ‘I’M A NAZI.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.