However many times one absorbs the brevity of the interlude between the first catastrophic worldwide conflict of the 20th century and the next, it was the not-knowingness of that timetable that allowed society to cope. In the 20 years between world wars that shattered several generations, Britain’s full emotional recovery was never really accomplished. But with his eye for the political and the cultural, for the game-changing and the deliciously absurd, for comedy and for tragedy, Alwyn Turner demonstrates the irrepressible optimism of humanity, whatever the circumstances: ‘Highbrows and lowbrows [lived] cheek by jowl, rubbing along with politicians, priests and pressmen.’ Relentlessly twisting the kaleidoscope, Turner finds a stunned nation navigating what became an increasingly turbulent pause.

With the armistice in November 1918 and the prime minister David Lloyd George adapting H.G. Wells’s phrase that Britain had just emerged from ‘the war that will end war’, buoyancy initially felt tenuous. No bodies were returned from the battlefields, the potential scale of such an undertaking preventing it, so no funerals took place, no graves were dug and no conventional rituals guiding the process of mourning were followed. Without any evidence of death, grieving happened in a vacuum.

Even as the negotiations to bring the conflict to a halt were being conducted across Europe in the summer of 1918, more destruction was approaching. Spanish flu, a plague on a scale not seen since the Black Death, and eventually accounting for five times as many deaths as the war itself, was met with such horror that it was barely spoken about. Although the annual commemorations of the armistice were celebrated in a spirit of national unity, with a series of innovations, including the observation of a two-minute silence, the wearing of a poppy, the burial of a symbolic unknown warrior and a cenotaph at the centre of Whitehall representing the ‘Glorious Dead’, people were keen to move on from the sorrow towards long-term peace. In fact what Turner calls a ‘cultural silence’ became a placebo with which to deal with collective trauma.

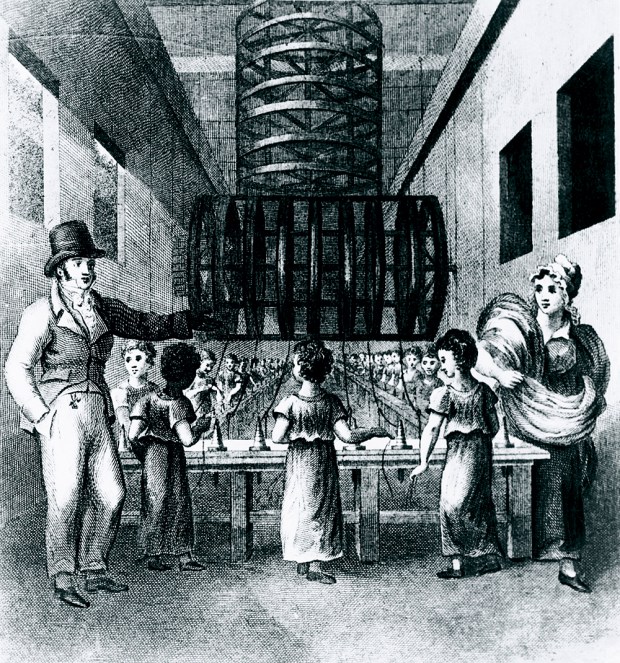

But the 1920s world soon became unrecognisable. Suffrage had transformed society, so that by 1928 most women were incorporated into an electoral voting system four times its prewar size. The world seemed to contract as technological advances made remote places suddenly accessible by car and aeroplane. The ubiquity of the radio, the biggest communication development since the printing press, allowed millions to hear the voice of their monarch for the first time on Christmas Day 1932.

Unlike America, with the Ku Klux Klan, or France, with its paramilitary organisation La Cagoule, or Spain, engulfed by civil war, Britain was devoid of political extremism. Yet the economic paralysis resulting from the Depression, the ebb and flow of political power and the crisis involving Wallis Simpson all found their place. There was a dizzying change of prime ministers and a change of crowned heads, too. Throughout the two decades, the Conservative, Liberal and Labour parties all competed for leadership, while taboos concerning divorce derailed the marriage plans of a king who had no option other than to abdicate.

Spanish flu, a plague on a scale not seen since the Black Death, was met with such horror it was barely spoken of

Turner’s emphasis, however, is on the full cultural, sporting and recreational scene, with ‘a bias towards the popular’. His stories range through music hall, dance, art, Noël Coward, cinema, poetry, Mills & Boon romance, architecture, new confectionary (Crunchies, Mars Bars, Kit-Kats), the BBC and the building of football stadia and Butlin’s holiday camps. Though involving considerable social and technological progress, the interwar years were also ones of caution and vigilance. Movements for nude sunbathing and cross-dressing were roundly condemned.

By the early 1930s, the fear of conflict loomed again, although Oswald Mosley’s fascist movement never truly caught alight. But in an account bristling with tension, we see Neville Chamberlain’s 1938 Munich Agreement, and his assurance that ‘appeasement’ of Hitler had done the trick, followed by plunging disillusionment as the promises come to nothing.

I wish I’d had a history teacher like Turner, with his idiosyncratic gift for wit and tenderness, describing how things were done in the past by people who feel as knowable as if they were alive today. This is history at its most fun, immersive, human and revelatory.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.