It is only sixteen months since Australians discovered, by accident, that the Albanese government had granted visas to Gazans who expressed sympathy for Hamas, the proscribed terrorist organisation that controls the Gaza Strip and has turned it into a hellhole for the 2.3 million people who live there. Some applications were approved in as little as an hour, without face-to-face interviews. Sympathy for the devil was not, as Asio director-general Mike Burgess put it, a ‘deal-breaker’. Applications for refugee status have already been lodged.

It was also only after sustained opposition pressure that the Minister for Home Affairs and Immigration, Tony Burke, admitted that around 3,000 visas had been issued to Gazans, more than by most comparable Western countries. How many have expressed views that are incompatible with Australian laws and values is unknown.

By contrast, Gaza’s closest neighbours, Egypt and Jordan, have formally refused to accept any Gazans for resettlement, citing the risk of destabilisation by Hamas, a chapter of the Muslim Brotherhood, a group that Egypt has declared a terrorist organisation, and Jordan has stripped of legal status. These governments do not indulge the deadly Western conceit that Islamist movements can be safely compartmentalised from politics, security, and social order.

The most recent unwelcome revelation came last October, when the government conceded it had held secret discussions about the return of Isis supporters, reportedly two women and their four children, from camps in Syria, where Islamic State ideology is still rife. The government insists it did not facilitate their return, but the larger question remains unanswered: why have dangerous people been released into the community despite the national security risks?

Isis is a proscribed terrorist organisation. Supporting it by travelling to its appalling caliphate, assisting it, including assisting its fighters with domestic duties, or encouraging others to support it by praising it, attracts the most severe criminal penalties. Yet the public still has no answers to basic security questions about these returnees. Did they express sympathy for Isis? Was that a deal-breaker? Who knows?

What we do know is how seriously Isis, like Hamas, takes the indoctrination of children. No Australian who saw it, will ever forget the image tweeted by Isis fighter Khaled Sharrouf in August 2014 of his smiling seven-year-old son holding the severed head of a Syrian soldier.

Sharrouf, like his associate Mohamed Elomar, was born in Sydney to Lebanese Muslim parents. Like Naveed and Sajid Akram, their cases illustrate a pattern identified by Western intelligence agencies: the risk associated with Muslim migration is not confined to the first generation. Jihadists are frequently second-generation migrants, raised between two moral universes, experiencing identity fracture, grievance, and alienation. Islamism functions as a counter-cultural rejection of Western values and mainstream Islam alike. This risk is magnified by migration into pluralist societies that are committed to individual liberty and free expression from conflict zones shaped by sectarian violence, authoritarianism, and jihadist narratives. This is not prejudice; it is prudence.

Countries with the fewest instances of Islamist terrorism, such as Poland, Hungary, Japan, and the Czech Republic, share common features: strict immigration control, low intake from jihad-producing regions, rapid deportation where legally possible, no ‘asylum first, security later’ approach, and no multicultural indulgence of parallel legal or religious systems. Cultural integration is expected, not optional. Extremist preaching is criminalised. Terrorist sympathy triggers police investigations, not excuses.

Countries with recurring Islamist terrorism, such as the UK, France, Belgium, and Germany, share the opposite traits: large, self-segregated Muslim populations, a multicultural ideology hostile to assimilation, reluctance to act on intelligence early, and a refusal to name Islamist ideology as causal. No prizes for guessing where Australia fits.

What the government refuses to acknowledge is that the state not only has the right but the duty to preserve its civilisational foundations. A liberal society cannot survive if it tolerates illiberalism. Not all cultures are compatible, and importing incompatible norms at scale creates real danger. Migration must be treated as a privilege, not an entitlement. Those who come here must accept Australian values: one law for all, equality of men and women, freedom of speech, secular authority, and the legitimacy of the Australian state.

Multiculturalism, one of the most poisonous legacies of the 1970s, was a profound mistake. Assimilation worked. Migrants from many backgrounds were expected to learn English, adopt Australian civic norms, including dress codes, and integrate into a shared national identity. That model produced a high-trust society and avoided large-scale communal conflict.

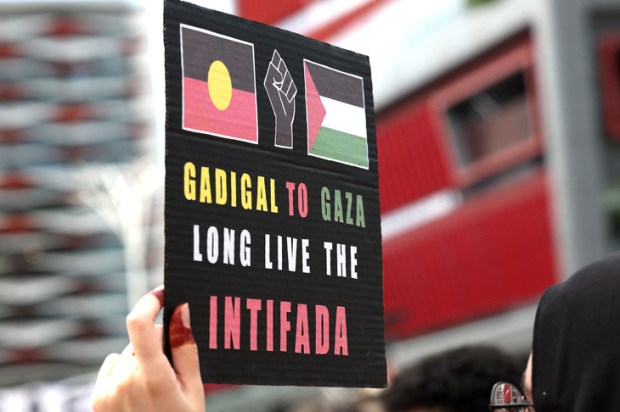

Instead, we now find ourselves in a morass of moral relativism. Given that the threat comes from within as well as without, Islamism must be policed. There must be transparency on foreign funding of religious institutions, prosecution of those who glorify jihadist violence, removal of non-citizen extremists, and zero tolerance for radicalisation in prisons. Jew hatred cloaked in hadiths should be criminalised. Protests should not be banned, but they should not be permitted to paralyse critical infrastructure or city centres; redirect them to parks or playing fields.

The defining characteristics of the Albanese government are its ideological distance from mainstream Australia and its electoral sophistication. It badly lost the Voice referendum but won a decisive election last year. Yet within six months, it is in trouble again. A YouGov poll showed 62 per cent of voters believed the government had handled Islamic extremism badly or very badly, statistics reminiscent of the defeat of the Voice. That electoral warning, rather than recognition of its errors or national-security reality, is what has forced Albanese to belatedly float the possibility of a royal commission.

This brings us to arithmetic. Terrorism is a numbers game. The overwhelming majority of proscribed terrorist organisations in Australia are Islamist, and the most lethal terrorist attacks against Australians have been carried out by jihadists. Counter-terrorism is not an abstract exercise; it is triage but with limited resources. That is why migration matters. Every additional person assessed as a risk competes for the attention of limited manpower. Security agencies acknowledge that this is why Naveed and Sajid Akram were not under active surveillance. Entry decisions increase the denominator. Surveillance does not scale.

The government knows this, yet it has behaved as if the risk were negligible and capacity elastic. It prioritised its electoral calculus over the strain on overstretched security services. This was governance by numbers, but with a fatal flaw at its heart. Albanese gambled that he could put electoral advantage ahead of social cohesion and national security: ballots before bullets. He lost the bet. Others lost their lives.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.