I write spy thrillers that attempt to deal authentically with the world around us. The Syrian civil war. Spy games with Vladimir Putin. Russian meddling in the US. The shadow war between Israel and Iran. Tension inside the US-UK intelligence partnership. These are the settings for my first five novels, and in all of them fast moving and unexpected events in the real world have disrupted my plotlines, rendering portions of the books ‘OBE’, as we used to say back at Langley: overcome by events. The real world, more and more, is scooping the spy novelist.

Exploding pagers? That would be too much. It would strain credulity

Spy novels, of course, have always been in conversation with reality. Before the first and second world wars, the genre’s greatest authors, such as Erskine Childers, focused on the rising German threats. After 1945, most of the genre’s leading writers – from the slow-burn end of the spectrum (think John le Carré and Charles McCarry) to the more pyrotechnic (think Ian Fleming and Tom Clancy) – concentrated their energies on the threat from Moscow.

Since then, spy fiction has shone a light on conflicts from the War on Drugs to Vietnam to Afghanistan, Iraq and the War on Terror. The thin membrane between fiction and reality has always been one of the genre’s strengths. Readers come to spy fiction, in part, to understand what is going on in far-flung corners of the globe, and why.

But something has changed. Global geopolitics – the nursery from which all spy novels are hatched – has become more conflict-ridden. This conflict is happening on a wider scale. And the rate of change is faster. This means that the humble spy novelist faces a challenge: how to craft the world of a novel that will resonate with readers in two years’ time, when the novel is published. Because one or so years – if not more – will be required for research and writing, and another so it might be manufactured, distributed and marketed properly. In today’s world, this is the equivalent of aiming a rocket at where the target moon or planet will be in a few years’ time, but without the benefit of knowing its orbital path or speed.

Take, for example, that Israel-Iran setting I mentioned. I began writing the novel that would become my latest, The Persian, in the autumn of 2023. I had a vague notion that the plot would focus on the conflict between Israel’s Mossad and Iran’s intelligence services; my characters would participate in this high-stakes game of sabotage, kidnapping and assassination.

A few months after I began writing, in the spring of 2024, Israel bombed Iran’s embassy in Damascus, Syria, and the Iranians retaliated by launching around 300 drones and missiles back at Israel. The shadow war, it seemed, was bursting into the open. My plot centred on a tit-for-tat spate of killings between the intelligence services of both countries, and here we were, witnessing one in real time. I began rewriting vast portions of the draft.

Then, as I was nearing completion, Mossad conducted the now infamous pager attacks in Lebanon. The Israelis pulled off an intelligence coup by feeding explosive-laden pagers into Hezbollah’s supply chain in a successful bid to bruise the group’s command and control and wreck its morale.

This burst of raw, brutal reality seemed far more potent and also – somehow – more ludicrous than anything I could cook up for the plot of my novel. If I had proposed this idea before the actual events, my editor would have told me to go back and try again. Exploding pagers? Pagers? That would be simply too much. It would strain credulity.

And yet here we were, in a world where it had happened. I wondered if my own plot was sufficiently cutting-edge, or if it would appear almost quaint to readers who now understood what Mossad was capable of. To account for reality, I tried to juice things up in my own novel.

But reality kept on coming. Last summer, as the book was going to print in the US, Donald Trump struck Iran’s nuclear programme and there was a 12-day war between Israel and Iran. And now, weeks before publication in the UK, the Iranian regime has massacred tens of thousands in a bid to suppress the worst unrest the Islamic Republic has faced since its inception in 1979.

The Middle East from all the way back in the ancient days of 2023, a mere two years ago, is no more. The rocket I aimed into the outer space of the Israel-Iran shadow war has landed somewhere, certainly, but in this geopolitical environment it’s getting damn near impossible to be certain it will hit the mark. When Fleming penned Casino Royale, or when le Carré wrote The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, I doubt they ever had to consider the wholesale collapse of Soviet communism as a possibility during their publishing timelines. (Though, yes, if you were writing a book about Iran in 1979, or the Soviet Union in 1989, I offer my sympathies.)

I woke up in the bizarre and uncomfortable position of hoping that Putin survived the mutiny

And lest you think the geopolitical disruptions to The Persian were isolated incidents, let me offer two more examples from my own experience.

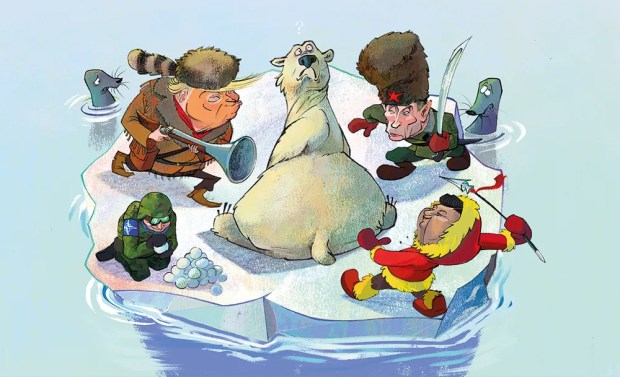

First, while drafting my second novel, Moscow X, Putin invaded Ukraine toward the end of my first draft, and faced down the mutineer Wagner chief Yevgeny Prigozhin a month or so after I’d finished the final edit. Putin himself was a character in the novel, and so I woke up on the morning of the Prigozhin mutiny in the bizarre and uncomfortable position of hoping Putin survived, merely from the standpoint of plot continuity. I am also being scooped right now. My fifth novel – I’ve just sent a draft to my publishers – is about the relationship between the US and UK, in particular the tight connections between its spy services.

When I started writing early last year, I began with this premise: what if the trust between CIA and MI6 so weakened that the two services began, in select areas, to spy on one another? I’d picked the US-UK setting in part to avoid the geopolitical storms in much of the rest of the world. I figured that, given the strong bonds between the two services, I’d have to concoct some highly creative and perhaps downright implausible plotlines to sink transatlantic relations to new lows… oh, wait.

Tariffs and trade wars. Disputes over intel sharing with Ukraine and the US approach to striking drug boats in the Caribbean. An FBI director who wants to rework the schedule for the annual Five Eyes conference to incorporate Premier League matches, helicopter tours and jet ski rides. And then there is the potential war over Greenland. Yes, Greenland.

Spy novelists may not know quite where to aim, but what’s clear is there will be plenty of material to gather along the way.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.