Last year might have proved a good time to own shares in the chip-maker Nvidia, along with the booming American tech giants. Or a piece of the defence manufacturers as the world re-arms. Or to hold a position in some of the rapidly growing economies of South America or Asia, or even one of the hyped-up crypto currencies. There were plenty of places investors expected to make money over the past year.

As it turned out, however, there was one asset that outpaced them all, even though it generates no income: gold, and to an even greater extent, its junior sibling silver. With government debt soaring out of control, the precious metals are more valuable than ever – and so long as that is true, they will keep on climbing.

There is no question it was the stand-out asset of last year. The gold price rose by 60 per cent, from $2,600 an ounce when the year started to more than $4,500 by its end. Silver has been on an even more spectacular run, more than doubling in price, from $30 an ounce in January last year to $79 an ounce shortly after Christmas.

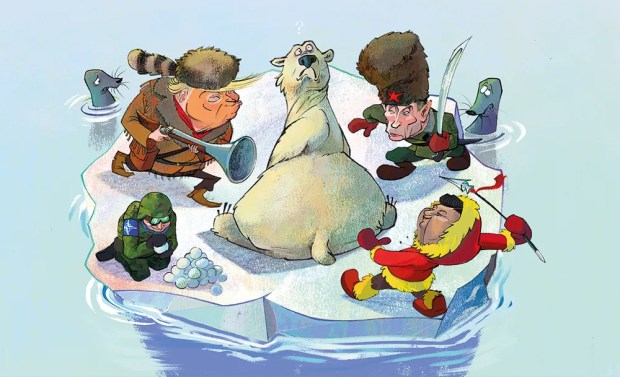

As the new year started, that bull run showed no signs of slowing down, with gold and silver both hitting fresh highs as Donald Trump unleashed a fresh round of tariffs. 2025 was the best year for the precious metal since 1979, the year of the Iranian revolution and the second oil crisis, and it easily out-performed most other major assets. It beat the benchmark US index, the S&P 500, which rose by a mere 16 per cent over the year, the FTSE100, up by 21 per cent, and global equities excluding the US, up by 29 per cent. Its digital rival, bitcoin, which to its enthusiasts is a modern version of gold that is easier to trade on your phone, ended the year 1 per cent down. On any measure you care to look at, the world’s oldest form of money beat any of its more modern competitors.

Gold has always fascinated both thriller writers and conspiracy theorists, and if you search around on the web you can find plenty of sinister explanations for the surging price: the ‘global elite’ might be prepared to reimpose the gold standard; the Chinese government is buying it ahead of its invasion of Taiwan; or American officials are trying to replace all the gold in Fort Knox, which apparently went missing years ago. There is an outlandish theory to suit every taste. The real explanation is very simple. It is the only way to hedge against soaring government debt.

Over the course of the past year, it has become painfully clear that the world is drowning in debt. In the United States, the budget deficit remains more than 5 per cent of GDP, and Trump shows no signs of bringing it under control. Taxes are still being cut, and the revenue from tariffs will be distributed in handouts as well. Total US debt now stands at $38 trillion, $15 trillion more than in 2020. The cost of servicing all the debt has broken through the $1 trillion-a-year barrier for the first time.

America is far from alone. Japan is still borrowing close to 4 per cent of its annual output, and its total debt to GDP ratio is above 230 per cent. France, which has overtaken Italy as the third-biggest borrower in the world, is stuck in a parliamentary deadlock, with its political class unlikely to agree on any plans to reduce an annual deficit of more than 5 per cent of GDP. Britain’s Chancellor, Rachel Reeves, has ramped up borrowing by an extra £70 billion, even though the economy has stalled, and, given how much of the money is spent on welfare, there is little prospect of it boosting growth.

For years, Germany was the one major economy that refused to join the party, with a constitutional brake on the amount the state could borrow, but it has now thrown off those shackles, with a deficit that will rise from 3 per cent last year to close on 5 per cent by 2028, as it spends billions on defence and combatting climate change. The European Union, perhaps because the credit of its members has been maxed out, has started issuing debt of its own. It borrowed €800 billion for the pandemic recovery fund, followed by another €150 billion for defence, and then another €90 billion to fund Ukraine, given that no one in Europe actually wants to put forward any of their own money to stand up to Russian aggression.

Major economies can’t make radical spending cuts, so central banks will end up devaluing paper money

The major global economies have plenty of differences. But they are united on one point: they keep on borrowing more and more money. No one quite knows when it will happen, but at some point there will be a reckoning. Governments won’t be able to make the radical cuts to spending that would be required to balance the books; their voters won’t tolerate it. Nor can they raise taxes sufficiently to cover all the bills. Once they can’t borrow any more, there will be only one option left. Central banks will have to print more money. Gold will hold its value while paper money is devalued, and silver as its junior partner will keep on rising alongside it.

Nothing else has the same ability to protect investors from the debasement of the currency. Cash will be worth less and less as more of it is printed. The yields on government bonds won’t keep pace with inflation. Equities might perform better than most other assets, especially the big multi-nationals with solid profits and generous dividends, but they will struggle to keep pace with rising prices, and they are already over-valued. Bitcoin has failed to prove itself as a reliable store of value.

Add it all up, and one point is clear. In a world of soaring government debt, gold is the only real hedge. So long as that is true, it will keep on rising. The bull market in precious metals still has a long way to run.<//>

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.