It is still unclear what will happen next in Iran. I fervently hope the current protests will cause the tyrants of Tehran to fall. It would be ideal if they were replaced by an order that allowed the population of 90 million to choose who governs them and build a country that reflects joy, hope and modernity rather than Ali Khamenei’s brutal Islamist fever dream.

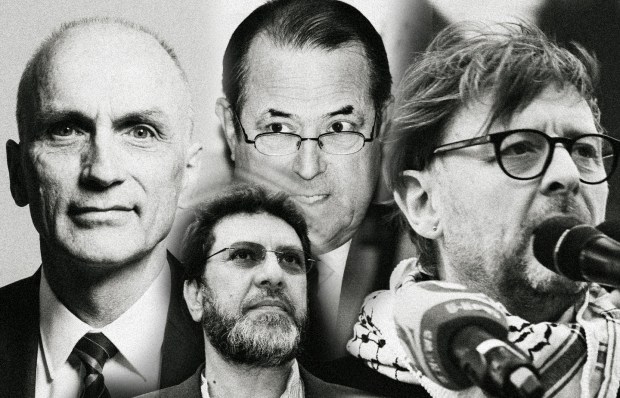

I also know how unlikely that is. Revolutions tend to produce disorder and repression, not order and freedom. After the failure of the Constitutional Revolution in 1911, there was a decade of chaos, fragmentation and insurgency in Iran until Reza Khan seized power and founded the Pahlavi dynasty. In 1979, his son was driven into exile by a revolution welcomed by progressives – including the unspeakable Michel Foucault, the radical feminist Kate Millett and the international jurist Richard Falk (who was happy to criticise Israel at the drop of a hat). That turned into an obscurantist nightmare and a decade of war.

And since the death in 1989 of Ayatollah Khomeini, the signature achievement of the current Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Khamenei, has been to turn Khomeini’s personalised theocratic tyranny into a financially centralised, highly organised and brutally repressive praetorian state protected by hundreds of thousands of ideologically indoctrinated Basijis (the thuggish street militia) and the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). There may be a question mark over the regular army, the Artesh. But if the Basij, the IRGC and the religious elite remain cohesive, the regime will survive for now – no matter what the cost in human life.

There are people – all Iranian – whose views on these matters I greatly respect: Karim Sadjadpour, Ali Ansari, Behnam Ben Taleblu, Saeid Golkar and Holly Dagres, for example. There are some – step forward Owen Jones – who have become instant experts and want to ensure mostly that neither the US nor Israel benefits from the Islamic Republic’s collapse. There are others in the region who see Iran through the prism of realpolitik and worry about the impact a sudden collapse could have on their countries: the Turkish foreign minister is one, as are several prominent Saudi and Gulf analysts. Given the chaos that followed the Arab Spring, that is an understandable position.

It may be that they also fear the emergence of a free and dynamic Iran in competition with their own countries. If such an Iran, with its extraordinary geostrategic assets, were to rejoin the concert of nations, it would represent a sea change – economic, political and social – not just in the Middle East but globally.

As for our own government, it remains unclear exactly what they think. Foreign Secretary Yvette Cooper proudly said on social media on Tuesday that she had scolded Abbas Araghchi, the Iranian foreign minister, and told him to ‘end the violence’. I hope Araghchi has recovered from the wigging. She has also promised ‘legislation’ on some vague new sanctions. Given that the government seems incapable of producing timely and sound legislation on other matters, I am not holding my breath.

If a free Iran were to rejoin the concert of nations, it would represent a global sea change

I was a co-author of a report for Policy Exchange in 2023 suggesting a new Iran strategy for Britain. Among other things, it recommended using financial intelligence to identify and interdict illegal funding flows, refocusing our more general intelligence effort to respond to the regime’s brutality, boosting the BBC’s Persian Service, encouraging a renewed focus on badly eroded Farsi language skills and area expertise within government, and working with regional partners to counter Iranian subversion in the region. In particular, we recommended finding a way – as the Independent Reviewer of Terrorism Legislation had suggested – to take action against those parts of the IRGC active in Britain or harming our interests elsewhere and shut down other malign Iranian-backed institutions operating here. Nothing happened. The usual excuse was that it would lead to a diplomatic rupture and we needed representation in Tehran in order to explain to the regime what we thought.

I understand why the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office would like to keep open our two magnificent and historic compounds in Tehran. But – as I know from the long and dismal hours I used to spend with them – the absence of Iranian diplomats in London would be no loss at all. And the idea that a diplomatic presence in Tehran lets us speak directly to the regime – and so shape their views – is for the birds.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Tehran is designed not to provide but to obstruct access to key decision-makers. Sometimes the illusion is created that access is possible: during the negotiations that led to the signing of the nuclear agreement – the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) – in 2015, Iran’s then foreign minister Javad Zarif played his American and European opposite numbers like a violin. But he was a taker, not a maker, of decisions: the organ grinder’s assistant, while the organ grinder and his real advisers remained inaccessible.

Javad Zarif smiles on his return to Tehran after the JCPOA was signed, 15 July 2015 Scott Peterson/Getty Images

In any case, if the regime wants to know what we think, they can scan social media and read the British press. Whether they would believe what they read is a different matter: the mindset of many of the Shia fanatics who run Iran is likely to be only a slightly more sophisticated version of that demonstrated in Iraq by the Iranian-backed militiamen who kidnapped Russian-Israeli researcher Elisabeth Tsurkov in 2023, which she recently described in a piece in the Atlantic entitled ‘Kidnapped by idiots’.

We are seeing yet again the true nature of the regime and our response is to condemn – then do nothing

The FCDO might also plead that we need to be represented in Tehran to live up to our obligations as a member of the European troika, with Germany and France, which continues to act as if the JCPOA still meant something. But why? Having triggered snap-back sanctions in the autumn, what else is there to say or do? And if there is anything, the ball is firmly in Iran’s court, not ours.

There are other indications of endemic institutional feebleness in this country: the reopening in 2023 of the Islamic Centre of England in Maida Vale, long accused of links with Tehran, or the continued functioning of the Islamic Human Rights Commission, which William Shawcross in his review of Prevent identified as aligned with the Iranian regime. Even when a stockpile of ammonium nitrate was discovered in 2015 in a flat in north London allegedly for use by Lebanese Hezbollah, Iran’s overseas agent of choice, it was kept very quiet. The press subsequently speculated that this was linked to the need to keep the Iranian nuclear deal afloat. It all resembles the way successive governments have sought to treat a wide range of malign Islamist bodies and organisations in this country and abroad with kid gloves ‘to keep lines open’. But the only lines I have ever observed being kept open are the ones that feed back into this country and undermine its security and cohesion.

We are seeing yet again the true nature of the Iranian regime in the mass murder being committed every day on the streets of Tehran and other cities across the country. They have been doing this for decades, whenever they feel under threat. Our response is to condemn – but then do nothing. It’s almost as if our political leaders agree with the Iranian regime that we can never atone enough for our vastly exaggerated role in the collapse of the Mosaddegh government in 1953 (spoiler alert: I know that some do).

Perhaps this time, we might think about doing something instead. And the FCDO could do a lot worse than dust off our 2023 report and start to implement at least some of its recommendations. The alternative is more paralysis in the UK and another false dawn for Iranians. They deserve better.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.