Following America’s extraordinary raid on Venezuela last week, Donald Trump has pointed to Greenland, which belongs to the Kingdom of Denmark, as the territory he plans to turn his attention to next, staking a claim he has made repeatedly since his return to the White House. Trump said this week that America needs Greenland ‘for national security. Right now’. He told reporters he is ‘very serious’ in his intent.

The US President might be claiming Greenland in the name of peace and stability, but there is every chance his neo-imperial attempts to see off the threat from China and Russia will backfire. Will his actions herald the return to a land-grabbing, power–flaunting global order like that of the 19th century? Crucially for Europe, could Vladimir Putin see America’s actions in Venezuela and ambitions for Greenland as a justification to reach further west in his bid to restore the fabled Russkiy Mir of Russia’s tsars?

‘We cannot sit back and assume that a possible Russian attack won’t happen until 2029 at the earliest’

This question is certainly worrying Europe’s leaders. Last month, Nato chief Mark Rutte travelled to Berlin to warn that Russia could be ready to use ‘military force’ against the alliance by 2030. ‘Conflict is at our door. Russia has brought war back to Europe, and we must be prepared for the scale of war our grandparents or great-grandparents endured.’

Germany is one country responding to Rutte’s call to arms. In the coming weeks, letters addressed to German 18-year-olds will start dropping on doormats, inviting them to fill out an online questionnaire aimed at establishing their ability and interest in joining the army.

Thanks to Germany’s voluntary military service law, passed a few weeks before Christmas, the failure by any young man to fill out the survey will be punishable by a fine. (For the moment, the quiz remains optional for women.) Any young person who expresses willingness to join the Bundeswehr will be invited to an in-person assessment and medical. According to the German ministry of defence, this recruitment drive will affect approximately 650,000 people each year.

Most immediately, this survey will allow Berlin to conduct a kind of stocktake of fighting-age men who could be called on in a national emergency. Germany’s defence and security officials have been among the loudest in Europe in warning about the risk Putin poses to the continent. Martin Jäger, the Federal Intelligence Service chief, warned in October: ‘We cannot sit back and assume that a possible Russian attack won’t happen until 2029 at the earliest.’

Germany isn’t alone in reintroducing a version of conscription for fear of Moscow. In November, the French President Emmanuel Macron announced a return to national service. The first cohort of 3,000 18- to 25-year-olds will embark on ten months of service this summer. Under the scheme, young French men will be assigned to military units across the armed forces. Macron has stated he hopes to increase the number of national service volunteers to 50,000 a year by 2035.

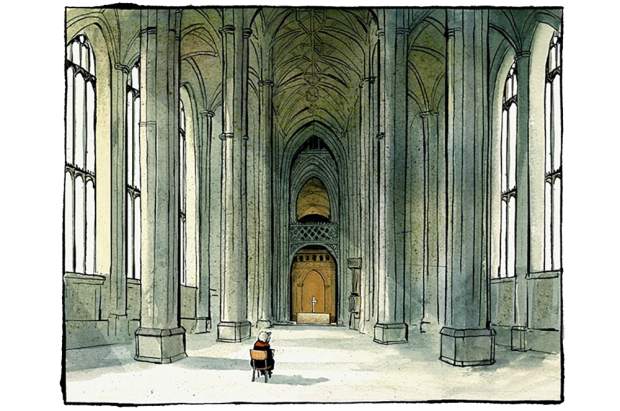

Emmanuel Macron reviews troops in Varces, French Alps Getty Images

The announcement has, on the whole, been greeted positively. One survey suggested that as many as 73 per cent of French people support the introduction of a voluntary military service programme. This is despite the leader of the French army, General Fabien Mandon, drawing ire earlier in the month for warning that the country may have to ‘accept the possibility of losing one’s children’ in a future conflict with Russia.

In Belgium, the introduction of voluntary military service across the three branches of its armed forces is also proving more popular than expected. According to the Belgian ministry of defence, more than 7,000 17-year-olds have registered their interest in information sessions on the year-long reservist scheme ahead of applications for the first tranche of 500 places opening this week. The Belgian army plans to accommodate volunteers in eight new barracks when training starts in September. Those young people who choose to leave at the end of their year as a reservist will be required to stay on the military’s books for ten years.

Meanwhile, the Dutch government has spent the past few months toughening up what was previously a lighter-touch approach to military service. Despite suspending conscription in 1997, the Netherlands retained its ‘conscription register’, writing annually to each fresh cohort of 17-year-olds – both boys and girls – to notify them that they had been placed on it. The government introduced a voluntary military service scheme in 2023, but it intensified its recruitment efforts last autumn after poor uptake – just 140 in its first year.

As of September, a second letter has been sent to Dutch youth, gauging how willing they are to join up for voluntary military service. According to the government, 200,000 people received the letter by the end of the year. Again, the hope is that this more direct style of recruitment will help meet the army’s target of more than doubling its size by 2030 – from 70,000 to 200,000, including reservists.

Several countries geographically closer to Russia have gone further, reintroducing military conscription. Latvia did so in response to Putin’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, making it compulsory for men aged 18 to 24, and optional for women. Conscripts are selected via a lottery to serve 11 months.

Poland has taken steps to prepare its population for the possibility of future conflict. With just over 216,000 troops, it already has the EU’s largest army and there are plans to expand its forces to 300,000 by 2035. In November the government launched a pilot scheme for a one-day citizens’ defence training course. The course offers Poles with no military background training in basic safety, survival, first aid and cybersecurity. More than 16,000 people took part in the pilot; Warsaw aims to train 400,000 civilians by the end of this year.

All these European countries have cited the growing threat from Putin as being behind the need to bolster their defences. But with Russia having struggled to subjugate Ukraine after nearly four years of war, some remain sceptical that Moscow would be strong enough, let alone daring enough, to attack a Nato member before the end of the decade. Is there another reason Europe is trying to grow its armies?

In a letter to the Dutch parliament’s House of Representatives in March last year, the country’s defence secretary Gijs Tuinman suggested this, writing: ‘The need for rapid access to this force has been crystal clear since the Russian invasion of Ukraine, but it is becoming significantly more urgent now that geopolitical realities are leading Europe to bear increasing responsibility for security on the continent.’

Europe’s leaders recognise the age of Pax Americana – living safely under America’s great wing – has ended

By ‘geopolitical realities’, Tuinman was referring to Trump. Since the start of his second term, the US President has been putting pressure on Nato member states to raise their defence spending. In June, they confirmed their aim to spend 5 per cent of GDP on defence by 2035. Nevertheless, security sources note that America has spent the past 12 months gradually withdrawing troops from Europe. This was essentially confirmed by the publication of a national security strategy in the autumn which revealed America’s aim to ‘readjust’ its ‘global military presence’ in the western hemisphere. The events in Venezuela last week – and the administration’s verbal threats to the rest of Latin America – align with this new policy.

Europe’s call to arms signals two things. There is the desire to show Trump that his demands are being taking seriously and that the continent is taking more responsibility for its own security; but perhaps more importantly, that Europe’s leaders recognise that the age of Pax Americana – living safely under America’s great wing – has ended.

What, then, of Britain? On 27 December, John Healey unveiled detailed plans for a ‘military gap year’ for under-25s to launch in March. The Defence Secretary has said it is part of the effort to ‘drive a whole-of-society approach to our nation’s defence’. It will, however, only aim to recruit 150 people this year, increasing to just over 1,000 across the army, navy and RAF by an unspecified date

The government will argue that this new scheme puts Britain in lockstep with its European neighbours. After all, as an island to the west of mainland Europe, the country’s defence priorities have always been different from those on the continent, who have a greater need for land forces.

And yet, by any measure, the aim to recruit under 0.02 per cent of 18- to 24-year-olds each year is paltry. This is characteristic of Labour’s unambitious approach to defence. The only reference to growing Britain’s armed forces in June’s Strategic Defence Review (currently there are just over 73,000 regular troops) was a line that there ‘remains a strong case for a small increase in regular numbers when funding allows’. There was no mention of any steps towards meeting Britain’s defence spending targets in Rachel Reeves’s November Budget. Healey’s Defence Investment Plan – setting out how the Ministry of Defence plans to spend its budget – was meant to be published before Christmas but has been indefinitely delayed. How or when the government intends to meet its Nato commitment to spending 5 per cent of GDP on defence remains a mystery.

On 23 December, first sea lord General Sir Gwyn Jenkins became the latest British defence and security chief to warn of Britain’s vulnerability to attacks from Russia. ‘We effectively… do have a border with Russia,’ he said. ‘It’s the open seas to our north, and any complacency that somehow we have eastern Europe between us and that threat is a misplaced complacency.’

Europe’s new recruits may never need to see a day of active combat against Russia. Turning back west, few have contemplated what a US annexation of Greenland – one Nato member state executing a hostile takeover of part of another – would mean for the future of the alliance. But what if that were put to the test? Isn’t it better to be prepared? By falling behind, Britain is leaving itself exposed. The cost risks being greater than Starmer, Reeves or Healey may be prepared to contemplate.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.