Traders and merchants in Tehran closed their shops in protest and demonstrated against the deteriorating economy and the plunging Iranian currency that hit new lows on Sunday, December 28. Trading and business have now become nearly impossible as prices are rising not on a weekly or even daily basis, but rather on an hourly basis.

In the past, there have been several widespread uprisings in Iran that were put down brutally by the authorities. The last one in 2022, the Mahsa revolution, named after the young girl, whose dubious death at the hands of the security forces triggered off the national protest, shook the Islamic Republic to its very foundations. Unrest in 2017-18 and in 2019-20 also left indelible marks on the body politic of the Islamic Republic and exposed the political fragility of the system.

Some years before that in 2009, dispute over results of presidential elections leading to President Ahmadi Nejad’s second term, brought millions to the streets in an air of expectation for change that had gripped the entire country. Previously in July 1999, people’s hope in the ‘reformist’ President Khatami were dashed when he labelled them ‘seditious elements’ to be followed by a ruthless crackdown on the protestors. On almost every occasion the clerical establishment appeared on the brink of losing power but in the end brute force won the day.

Unforgiving political measures at home that curtail basic human rights, an economy suffocated by mismanagement, endemic corruption and international sanctions, and global isolation brought about by a revolutionary ideology that seeks change through violence, all call for a radical shift in Iranian political orientation. The so-called ‘reform movement’, never a serious alternative to the clerical establishment but rather a rival partner, hungry for power, has long been unmasked for its frailty and pretentious claims.

People are now looking outside of the country for political inspiration and leadership. The younger generations, who comprise the majority, long for the pre-revolution days when a sense of calm prevailed in the country, economy was flourishing, international respect was secured, and social freedoms were guaranteed. Even the most violent of political activists then, who actively participated in attempting to assassinate the Shah and his family, received a royal pardon. It is a far cry from the revolutionary era, when slight deviation from the dress code can lead to one’s untimely death.

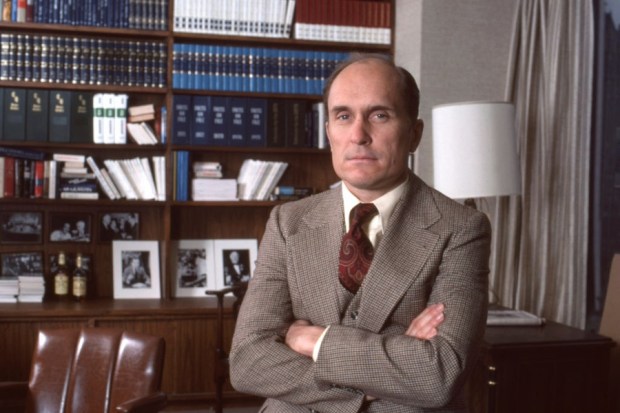

Crown Prince Reza of Iran, currently in exile in the US, has had increasing appeal to Iranians both in and out of the country. The considerable achievements of his father and grandfather during their 53-year reign in Iran have left a shining name in the collective memory of the people. The abysmal record of all other alternatives to the Islamic Republic has discredited the opposition bar the Prince. Chants of ‘long live the king’ are now commonplace in Iranian demonstrations.

A transition from an ideological system of governance to an organised, conventional and rational administration would be a fundamental shift in Iranian politics. It would give priority to national interests whilst desisting from interference in the affairs of other states. The preservation of the territorial integrity of Iran would not constitute a threat to others but rather promote regional cooperation and respect for the sovereignty of all states. It would foster social and political freedoms but fight terrorism at home and abroad. Iran would join the international community in combating money laundering by joining the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) and would resume her rightful place amongst the family of nations.

It is far from certain that the latest outburst of protest in Iran will this time tip the balance in favour of the people.

What is evidently clear, however, is that the people of Iran have long demonstrated their burning desire for deep-seated change that, though delayed by force, will eventually be theirs.