Nuremberg

Directed by James Vanderbilt

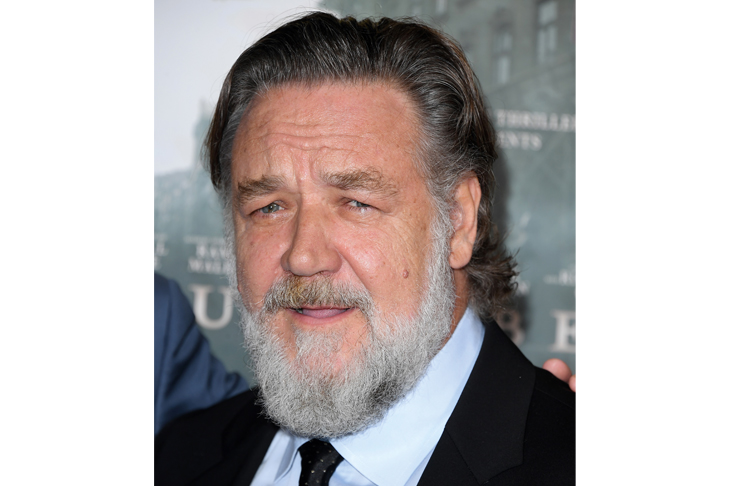

Starring Russell Crowe, Michael Shannon, Rami Malek, Leo Woodall

Before last Monday, the most recent film I had seen starring Russell Crowe was Master and Commander, released in 2003. Both Crowe and the film were very good. The sound effects were compellingly realistic: the creaking timbers of the ship, the lapping waves, and the groaning of the ropes and sheets were all there on the soundtrack.

On Monday night, I watched Nuremberg, a film about the first of the trials for war crimes, which took place in the restored Palace of Justice in Nuremberg from November 1945 to October 1946. It was the most important of a hundred or so trials conducted in Germany after the second world war. The story has been told many times. The two most senior Nazi leaders who were still alive after the war, Göring and Hess, were among the twenty-two defendants. Russell Crowe not only plays Göring but sounds and manages to look very like him. As good as the 1961 film Judgment at Nuremberg was, featuring Spencer Tracy, Marlene Dietrich, and a stellar cast of supporting actors, Nuremberg is at least a match for it. It is a timely film because one or two generations have little or no knowledge of the second world war and its aftermath, and because of the frightening revival of antisemitism. The focus of the film is Russell Crowe’s Göring and his role in the commission of genocide and other war crimes. The film is based on Jack El-Hai’s book The Nazi and the Psychiatrist. In real life, an army psychiatrist was ordered to interview Göring, which he did on many occasions with a view to gaining an understanding of Nazism.

Some dramatic licence is understandable and allowable. Crowe’s outstanding impersonation captures many aspects of Göring’s personality: his intelligence, his enormous vanity, his quick-wittedness, his total insensitivity and lack of remorse, as well as occasional flashes of charm. He even imitates perfectly Göring’s swagger as he enters the courtroom, indifferent to the fate of those who died in the gas chambers. The only thing standing between Crowe and an Academy Award is the evilness of the character that he portrays.

It did not seem unreasonable that Göring’s innocent daughter, a child not yet in her teens, was treated with humanity and tenderness, but the same cannot be confidently said of the similar treatment of Göring’s second wife, Emmy. She vied with Eva Braun to be represented as ‘the first lady of the Third Reich’ and ostentatiously enjoyed the trappings of wealth and power her husband acquired. Indeed, she was later tried and convicted for her role in public affairs and served a one-year term of imprisonment.

As the film progressed towards the climactic trial scene, I wondered how the screenwriter and the director would handle the incompetence of Justice Jackson, the American prosecutor, who was tied in knots by Göring rather than tying Göring in knots. For those familiar with the history it is well known that the cross-examination had to be taken over by Englishman David Maxwell Fyfe, an accomplished senior barrister appointed as assistant to Sir Hartley Shawcross, (colloquially known around Westminster as Shortly Flawcross) as leading counsel for Britain at the trial, who was absent, attending to domestic political matters in London at the time.

Jackson was a Justice of the United States Supreme Court who aspired to but did not gain the Chief Justiceship. He had been in private practice as an attorney for a period, but he was involved in public affairs before and throughout the war. It is worth noting that Warren Burger, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, made as speech in 1973 in which he said it was a mistake that his country did not follow the British system of a bar separate from other branches of the profession. It seems anomalous, indeed, not quite right to some, including this reviewer, that a judge might take off his judicial robes and don those of a prosecutor, albeit in a different jurisdiction. Sir Alan Mansfield, however, then a judge of the Supreme Court of Queensland and subsequently its Chief Justice before he became Governor, was one of the prosecutors in the Tokyo war crimes trials. Sir Alan had been an experienced and skilled barrister before his appointment as a judge. Lord William Patrick, an English judge who sat on the Tokyo trials, said on record how effective Mansfield was.

I doubt whether the screenwriter followed the transcript of the Nuremberg trials in writing the climactic court scene but, regardless, the scene is brilliantly conceived and executed, particularly by Crowe.

Emphasising that these are mere quibbles, two criticisms might be made of the film. It is entirely reasonable for sombre events to be filmed in sombre tones, but it did seem, at times, that the cameraman was trying to reproduce a chiaroscuro Caravaggio under a couple of hundred years of varnish rather than an optically clear image. In one scene, a character says, not just in a metaphorical sense, that the courtroom will be so brightly lit that the guards will have to wear sunglasses. Instead, at times, the audience would have been better aided by strong spectacles.

In the days of his vainglory, Göring not a stately pleasure-dome decreed, but a huge faux hunting lodge in a forest in East Germany, which he called Carinhall after his deceased Swedish first wife, adorned with more than a thousand paintings and objets extorted from Jewish owners. A scene in which Göring could be seen strutting through the grand hall of that lodge with his second wife on his arm would have served well to make the contrast between his shameless opulence and the horrors of the concentration camps. Such a scene could surely have been created with the aid of old photographs and computer-generated imagery. The lodge had been emptied and systematically demolished by Luftwaffe explosive experts in the last days of the war to prevent it or any of its contents from falling into Russian hands. For myself, I wish Crowe would spend more time making films than he does barracking for the Rabbitohs. They are formidable enough without Crowe’s support.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.