The Choral

Directed by Nicholas Hytner

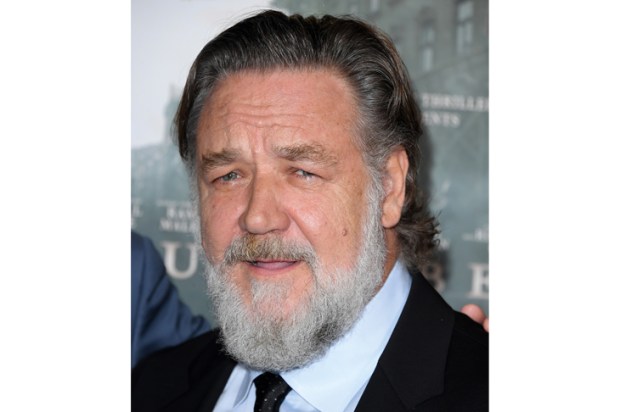

Starring Taylor Uttley, Ralph Fiennes, Mark Addy, Carolyn Pickles.

If it were in a contest, as it probably will be for a cinematic award, the film The Choral would start at very short odds. The screenplay is by Alan Bennett and is not an adaptation of any of his plays or stories. Ralph Fiennes plays the leading role of a recently appointed choral master of a community choir in the fictional town of Ramsden in Yorkshire in 1916. The director Nicholas Hytner previously directed earlier adaptations of Bennett’s works, The Lady in the Van and The History Boys. The story is plausible and moving, the scenery of the English countryside in summer is idyllic, the clothing of the period at the height of the Great War in 1916 is authentic, the production values leave nothing to be desired, various diversity boxes are ticked and at the heart of the film is a serious ethical question of the extent, if any, to which the work of an earlier artist may be reimagined by a later artist.

As a general proposition, it is true that all art is derivative, although some might seriously ask where on earth ‘Blue Poles’ came from. In The Choral, the committee of a community choir decides that its major performance for the year will be the oratorio of The Dream of Gerontius by Edward Elgar, principally because Elgar is British and not a German composer. Elgar is still alive, and his work is in copyright for his life and thereafter for a long period. Ralph Fiennes, as the musical director of the choir, writes to Elgar seeking a licence to perform the work, confident that, even though the choir is amateur, it will be granted because most great artists are vain and like to have their work performed. There are two other obstacles to be overcome, however. The enlistment and conscription of young men from the town have resulted in a shortage of male voices in the choir. The other is that there is really no one in the choir with a voice sufficient to carry the solos of Gerontius and his Guardian Angel. The strongly protestant committee of the choir has reluctantly come to terms with the Catholic theme of purgatory and the Catholicism of John Henry Newman, upon whose poem Elgar based the oratorio. Subplots include the fact that one of the choir’s young women is taken with another boy while her boyfriend is missing in action on the Western Front. Another is the yearning of the choral master for the young German man who is serving as a seaman in the German navy, in which he has enlisted. The pianist who accompanies the choir during its rehearsals is awaiting call-up and intends to maintain his conscientious objection to military service. The chair of the choir, a mill-owner, loves singing and is asked to stand aside from the role of Gerontius in favour of the young man who had been missing in action and returns to the town having lost an arm in action.

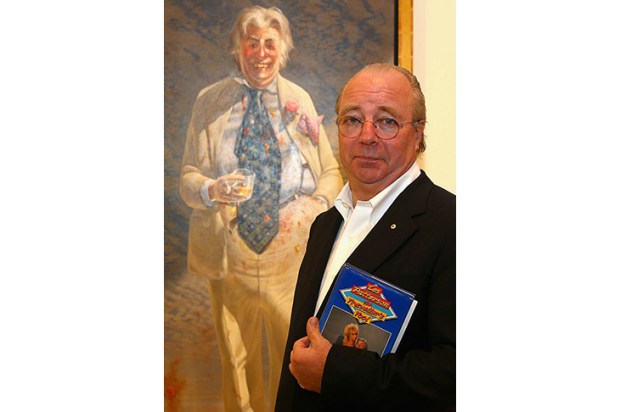

At this point, it should be said that Roger Allam’s performance as the chairman of the Committee is exceptionally good, and challenges that of Fiennes, who does not disappoint the high expectations his followers have of him.

As the choral master, Fiennes rules with a baton of iron. For those who may be unfamiliar with the earnestness and enthusiasm of amateur choristers, it may seem, at times, that Fiennes overplays the part. To attend a rehearsal, for example, of the Queensland Choir, an institution more than 150 years old, preparatory to its biennial presentation with some 130 or more voices at the Brisbane City Hall, is to gain an insight into the discipline exercised by the professional musician in charge of a community choir.

From the earliest motion pictures, railway platforms and steam-powered passenger trains have provided settings for many films. There are three particularly good ones in The Choral. One captures quite subtly the jingoism of the time with a scene on Ramsden’s platform, where a Salvation Army band plays and sings Churchill’s favourite hymn, Onward, Christian Soldiers, as the fresh-faced, now uniformed young men of the town board the train for the slaughter fields of the Somme. In another scene, the young soldier who has lost an arm receives no welcome, rousing or otherwise, when he leaves the train to return to the town. In a later scene, a detachment of young conscripts leaves for the Front while the police take away the pianist who has failed to persuade the conscription tribunal that he is a genuine conscientious objector. There are no Hollywood superheroes in this film.

The makers of The Choral have obviously taken great care to ensure that the settings are realistic and persuasive. I wondered whether the director might have visited the Imperial War Museum in London to view Lavery’s paintings of the interiors of some of the country’s great houses, which were converted into hospitals or convalescent homes to treat sick and wounded soldiers. There is one such scene in the film. Another could have been taken directly from Sargent’s poignant painting ‘Gassed’, which is also in the museum.

Unlike in Waiting for Godot, Sir Edward Elgar arrives for the final rehearsal of the reimagined Gerontius. The part is played by Simon Russell Beale with the same bluster and verve as James Robertson Justice, who played the role of the surgeon Sir Lancelot Spratt in the early non-bawdy original Doctor in the House films. To disclose how the ethical dilemma plays out would be a spoiler. There are good arguments on both sides of the issue, neatly framed in the film.

Whether this fine British film will receive an award remains to be seen. I would give it a mark of something between a distinction and a high distinction. It is well worth a detour and the price of an admission ticket.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Ian Callinan is the Patron of the Queensland Choir.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.