France seems to be witnessing more gratuitous attacks and stabbings. On Boxing Day afternoon, in the middle of central Paris, a man went on a knife rampage through the metro. He struck out at random, stabbing women on station platforms at République, Arts et Métiers and Opéra. There was screaming. There was blood. One of the victims was pregnant. There was no argument, no robbery, and no apparent motive. The attacks were entirely indiscriminate.

Random violence has become part of the background noise of public life

After each assault, the attacker didn’t run, he boarded the next train. Passengers recoiled. Doors closed. The train moved on. Station by station, through some of the busiest metro stations in the city, he continued.

This unfolded between four and five in the afternoon, when the underground was full of shoppers, commuters and tourists moving through Paris over the Christmas period. Yet no one stopped him. No one appears to have chased him. Police got to each scene too late.

When the rampage was over, the attacker left the network and travelled home, seemingly undisturbed. Hours later, police arrested him outside his house in Sarcelles, a densely populated northern suburb of Paris. Fortunately, no one died, although three women were injured.

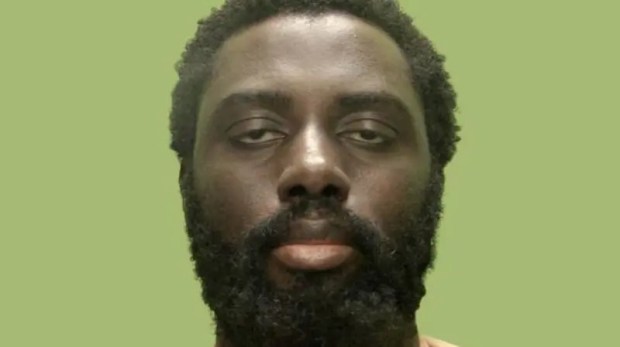

The suspect is a Malian man, already known to police. He had been imprisoned in January 2024 for aggravated theft and sexual assault, before being released in July this year. Five months later, he was free to roam central Paris on Boxing Day afternoon with a knife.

His release followed a period in administrative detention. He was held for the maximum 90-days designed to organise deportation. But Mali refused to provide the necessary consular documents to confirm his identity. He was under a form of house arrest, but otherwise left free, despite his criminal record. This deadlock is far from unique. Governments in countries such as Mali and Algeria frequently obstruct the return of their nationals, even those convicted of serious crimes, by delaying or withholding approvals. Relations with Mali have been particularly strained. Algeria, too, has repeatedly clashed with France over returns. Successive French governments have argued for tougher leverage, including restricting visas for officials, cutting development aid, or imposing EU-wide sanctions in order to force greater cooperation. Ministers have repeatedly insisted that countries which refuse to take back their own citizens must face real consequences. Yet the tools remain blunt, the diplomacy hesitant, and the outcome unchanged. Dangerous convicted foreign offenders who should have been removed are instead released back onto French streets.

The Interior Ministry has since revealed that the attacker, born in Mali, was naturalised French in 2018. This was only discovered after a passport was found at his home following the attacks. He never declared his French citizenship in any prior proceedings. This raises serious questions about administrative oversight and file interconnection, allowing a serious offender to be mistakenly treated as deportable while remaining at large.

After the attack the authorities moved almost immediately to frame the incident. Terrorism was ruled out within hours. The Paris prosecutor opened an investigation for attempted murder and made clear the attacks were not being treated as terrorist in nature. The suspect has since been moved to a psychiatric hospital.

We’ve heard this all before. In France, certainly, but also in Britain. Random attacks in public places are explained as tragic eruptions of mental illness. The attacker’s background is minimised. Immigration status is treated as incidental. Prior convictions are mentioned late, if at all. The violence is presented as inexplicable, and therefore unavoidable.

Attacks like this now follow a familiar script. They dominate the news cycle briefly, sometimes for a day, and then fade. Often, they barely register as major headlines at all. Random violence has become part of the background noise of public life.

The fact that this attacker had already committed serious crimes, had been in custody and released, barely featured in much of the mainstream coverage. It was acknowledged by only a handful of the press.

This pattern certainly isn’t new. It recurs with grim regularity. Convicted illegal migrants are released, removal orders go unenforced, and serious further crime follows. In September 2024, 19-year-old student Philippine Le Noir de Carlan was raped and murdered in the Bois de Boulogne. The prime suspect, a Moroccan national in France illegally, had previously been convicted of rape in 2021 and was under an order to leave France that was never enforced. The case triggered political outrage. Ministers at the time spoke of systemic failure and promised that such a crime would never be allowed to happen again. Procedures would change. Expulsions would be enforced, or those concerned would be held for longer. And yet, more than a year later, an illegal migrant previously convicted of serious crimes was once again free to roam central Paris, this time with a knife, on Boxing Day afternoon.

In Britain the narrative around violent attacks often follows the same pattern of focus on individual pathology rather than background. In Britain, knife crime is frequently explained in terms of social or mental-health causes, while questions about immigration status rarely dominate mainstream coverage.

The right will denounce the latest metro attack, as it has denounced so many before. It will point out that a country which cannot enforce its own expulsion decisions, cannot remove convicted offenders with no right to remain, and then expresses surprise when violence follows, is failing at its most basic task. It will no doubt be accused of exaggeration and stoking fear as a result. And yet the pattern remains. The same profiles recur. The same explanations are offered. The same decisions are defended. The same outcomes are absorbed.

Knife attacks that once would have shocked now flicker briefly before being forgotten. Sexual crimes are rising. Random violence is increasingly treated as normal. We cannot continue to ignore the fact that a growing number of these crimes are being committed by migrants who have already passed through the criminal justice system and been released back onto the streets. This is not a comment on immigration in the abstract – it is a statement about enforcement, about expulsion orders not carried out, about custody without consequence.

What’s tragic is no longer that these attacks happen, but how quickly they’re treated as ordinary and how quickly the profiles of the attackers are brushed aside.