I am feeling increasingly unwelcome in the country of my birth, as I am subjected to ubiquitous welcomes to and acknowledgements of country.

These declarations bring to mind the time our family undertook a journey in 1989 to the heart of Australia – Uluru – to climb what was then called Ayers Rock. We were among the many Australians at the time who saw this as a rite of passage.

In preparation for the climb, our 10-year-old daughter had used her pocket money to buy a t-shirt saying: ‘I climbed Ayers Rock’. Part way up the steep climb, she lost her nerve and wanted to return to the camp. Her older sister came to the rescue offering to help her, adding: ‘You can’t wear that t-shirt if you don’t complete the climb.’ Thus inspired, our young daughter reached the top with our whole family, where we were captivated by the breath-taking views.

However, since October 2019, would-be climbers of this iconic rock are unwelcome. The local Anangu people consider this site sacred and view climbing it as disrespectful. Scaling the rock is now illegal, and the first man convicted of breaching this law was fined $2,500.

Uluru is only one of many iconic destinations where non-Indigenous Australians are now unwelcome. Others include St Mary’s Peak and Lake Eyre in South Australia, parts of the Grampians in Victoria, Mount Warning in New South Wales, and Mount Gillen in Northern Territory. Many Australians are now feeling unwanted in their own country.

Several Australian leaders have called for scaling back Welcome to Country ceremonies, saying that the practice has become ‘overdone’ and ‘divisive’. Senator Jacinta Nampijinpa Price has said:

There is no problem with acknowledging our history, but rolling out these performances before every sporting event or public gathering is definitely divisive… It’s not welcoming, it’s telling non-Indigenous Australians ‘this isn’t your country’ and that’s wrong. We are all Australians, and we share this great land.

Provoking division

Many ordinary Australians strongly endorse Senator Price’s view, A recent public opinion poll by Dynata for the Institute of Public Affairs found that 56 per cent of Australians feel welcome to country ceremonies have become divisive, while only 17 per cent disagree.

A major problem with the constant repetition of welcomes and acknowledgements of country is that they provoke division between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians. Over time, dividing people in this way can foment resentment, mutual hostility and feuds that last for generations.

The best hope for avoiding such toxic tribalism is to treat all people equally, irrespective of ancestry. Equal treatment was implied in the instructions of King George III for establishing the Australian colonies some two centuries ago, and was explicit in Governor Hindmarsh’s proclamation of the Province of South Australia on December 28, 1836:

It is … my duty … to take every lawful means for extending the same protection to the native population as to the rest of His Majesty’s subjects … who are to be considered to be as much under the safeguard of the law as the Colonists themselves, and equally entitled to the privileges of British subjects.

Although this intention was more honoured in the breach than the observance, equal treatment was honoured when the first South Australian Parliament was established in 1856. All men over 21 were given the right to vote – both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal.

Today, all Australians – both Indigenous and non-Indigenous – could better encourage unity by celebrating the things we have in common.

Dubious origin

Another problem with welcome to country ceremonies is their dubious origin.

The first such recognisable ceremony was created for the 1976 Perth International Arts Festival. Polynesian dancers invited to perform at the festival said they would not present without a proper Indigenous reception, and so Welcome to Country was born.

It was said the creators adapted ancient Aboriginal customs in tribal lands to produce the Welcome to Country ceremony we know today. I asked friends who worked for a decade on Aboriginal tribal lands what they had seen or heard about such customs. They said they were not aware of any such ceremonies in the Aboriginal community among whom they lived.

The Welcome to Country ceremonies we frequently experience apparently bear scant resemblance to real Aboriginal customs. Some have even decided to stop performing them, such as the Juru people of the Burdekin Shire in North Queensland. They voted in 2024 to stop welcome ceremonies from taking place on their ancestral land. Indigenous leader Warren Mundine endorsed this decision. ‘Everywhere you go, you have a welcome … people are getting sick of it,’ he said.

Imposing religion

The coinventor of the original Welcome to Country ceremony explained that his Noongar words were a prayer to ‘spirits’. When translated into English, the words mean:

May the good spirit watch over you. You’re looking at the land of my people, we call Whadjuk. Later on when you go home to your country, may the good spirit take you safely home. May the spirits of my people and the spirits of your people watch over us now.

Listeners are being invited to participate in an expression of Aboriginal spirituality, a belief system centred on the Waugal creator spirit. The Waugal (with many different spellings) is a snake or rainbow serpent recognised in Noongar mythology as the giver of life, maintaining all fresh water sources. As it slithered over the land, the Noongar stories say, its track shaped the sand dunes, its body scoured out the course of the rivers, where it occasionally stopped for a rest, and created bays and lakes.

Insight into Aboriginal connection to country is provided in an episode of the ABC TV program Backroads, along the Bibbulmun Track in Western Australia. On this show, a local man performed a ritual honouring ‘the god that’s in this water’ – the rainbow serpent. By throwing some soil into the local river, he said he alerted the rainbow serpent to their presence and invited his ancestors to join them.

The Acknowledgement of Country is similar. In acknowledging Indigenous people as traditional custodians of country, we are affirming the rainbow serpent god of Indigenous religion. In paying respects to ‘elders past’, we are affirming Indigenous ‘ancestral spirits’, whose influence is respected and feared.

When federal government departments require staff to publish or declare Acknowledgements of Country on official occasions or in official documents, they are effectively imposing a religious observance. This is arguably a breach of the Australian Constitution s116.

Conclusion

The endless repetition of Acknowledgements of Country has become counterproductive. Instead of fostering harmony between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians, they foster separation and foment division. Australians are tired of their constant repetition and increasingly resent imposition of this religious practice. It is time to stop.

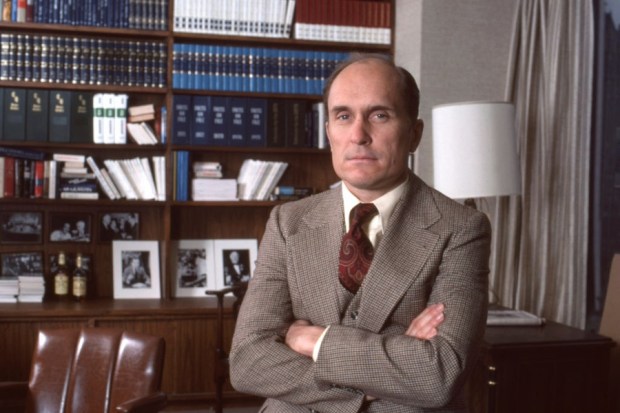

Dr David Phillips is a former research scientist and founder of FamilyVoice Australia