At the exit of the National Museum in Kinshasa, capital of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), is a whiteboard for visitors to leave their comments. On that whiteboard, full of underlinings and exclamation marks, are messages like this: “Thank you for your life.” “Thank you for our national unity.” “You left behind a glorious historical legacy. We plan to follow in your footsteps.”

A giant photograph of the man the messages refer to hangs in the museum’s main hall as part of its new exhibition, a man in dark glasses and leopard-skin toque, smiling down at his people. More than 28 years after fleeing into exile, Mobutu Sese Seko, once known as “The Leopard” and “The Great Helmsman,” is back in the limelight in the DRC.

This display of photographs of Le Maréchal in his prime, selected by his son Nzanga, would once have been inconceivable. Mobutu’s 32-year rule came to an ignominious end when Rwandan-backed rebels marched into the capital and he was execrated by the time he was toppled. Congo’s population blamed him for the country’s crippling poverty, the ubiquitous corruption and the collapse of basic services in one of Africa’s most resource-rich states.

As a plane carrying the cancer-stricken president and his family took off from the runway serving his Citizen Kane-style estate in equatorial Gbadolite, Mobutu’s loyal presidential guard actually opened fire on the aircraft in a final contemptuous salute to their departing boss.

But all that now seems forgotten – or at least partially forgiven. The exhibition, which opened on October 14 – Mobutu’s birthday – was originally intended to last just two weeks. But public reception has been so warm it’s now extended into December. My own suspicion is that it may become permanent. Many see the exhibition as preparation for the much-flagged return of Mobutu’s body from the Christian cemetery in Morocco’s capital, Rabat. When I met President Félix Tshisekedi, he confirmed that he favored the idea. “I’ve already given my approval. It’s now up to the family to decide what they want to do. One thing is clear: this would be an official event,” he told me in his presidential office, perched on a hill looking out across the city.

In 2022, he welcomed back the gold-crowned tooth of Mobutu’s late friend, the assassinated prime minister Patrice Lumumba – which was all that was left of him.

It’s an extraordinary position for Tshisekedi to take, given what his father, (nicknamed “the Sphinx”), suffered at Mobutu’s hands. A former minister and prime minister, Étienne Tshisekedi became Mobutu’s most implacable critic, and was at one stage banished internally. His children, including the current president, grew up in exile in Brussels. Some lingering rancor would be understandable. So why the volte-face? It doesn’t take a genius to work it out. You just have to look at what’s happening in the east.

By the 1990s, Mobutu had come to symbolize, both in Africa’s eyes and in those of the West, a generation of ideologically bankrupt “dinosaur” leaders who had outlived their Cold War usefulness and whose taste in pink Champagne, Parisian fashion brands and sprawling European real estate was utterly out of touch with their disenfranchised populations.

But at the start of 2025 a rebel group called the M23, once again armed by neighboring Rwanda, seized the capitals of North and South Kivu provinces, killing African peacekeepers, sending Congo’s army into flight and breaking up displaced people’s camps.

US-mediated talks got under way in June, and a deal between Tshisekedi and Rwandan President Paul Kagame was signed in December in Washington, DC: one of the many peace deals Donald Trump believes should have earned him the Nobel Prize. But the M23 pushed into the key city of Uvira just days after signing. This is the fifth Rwandan-backed rebel insurgency in the DRC and many analysts believe this time Kagame is bent on permanently redrawing the region’s borders. Despite Kagame’s stubborn denials that he has troops inside the DRC, experts believe Rwanda is committed to the restoration of a swath of territory which each year provides it with millions of dollars in smuggled strategic minerals.

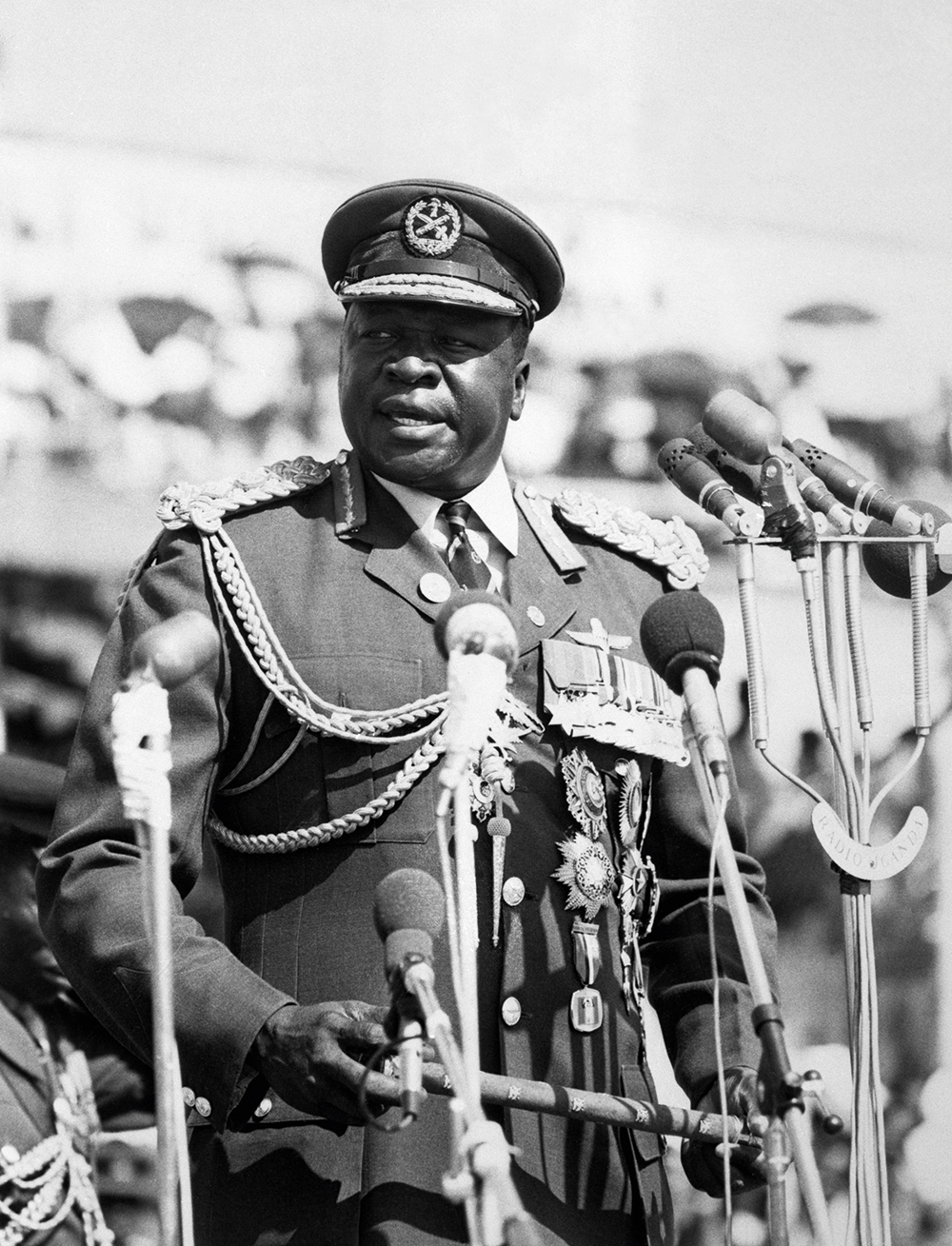

Former Ugandan president Idi Amin speaks at a military parade in January 1975 [Bettmann / Getty Images]

Former Ugandan president Idi Amin speaks at a military parade in January 1975 [Bettmann / Getty Images]

On the ground in the Kivus, the M23 has been appointing judges and chefs coutumiers (customary chiefs), sacking civil servants suspected of loyalty to the central government, recruiting soldiers and issuing title deeds: not exactly indications of a rebel movement readying to shut up shop.

The crisis has created a deep, gnawing sense of beleaguerment in Kinshasa. Congo’s territorial integrity is at stake, the term “Balkanization” is on everyone’s lips and all are keenly aware that for his many failings, Mobutu fought a series of wars in the 1960s and 1970s that prevented their vast country – often described as “the size of western Europe” – from disintegrating.

Under his rule, Zaire – as Mobutu rebaptized the country in 1971 – was a global player, famous for its cutting-edge fashion sense and infectious Lingala music. The exhibition at the museum in Kinshasa illustrates this point. We see Mobutu shaking hands with US presidents and strolling alongside Chairman Mao, debating with Henry Kissinger and riding to Buckingham Palace in a carriage with Queen Elizabeth. In part, the amnesia over Mobutu’s atrocities is the result of generational churn. Three-quarters of the DRC’s 109 million population are under 30: many were either babies or toddlers when Mobutu fled. They feel free to pick the legacy they prefer: dwelling less on the moules marinières famously flown to Gbadolite on a Mobutu whim, say, and more on the achievement that was the Inga Dams, one of Africa’s biggest hydroelectric projects of the 1970s.

Were I to argue with the DRC’s youngsters, I’d point out that Mobutu thoroughly destabilized his country by enabling Lumumba’s elimination in 1961, staging two coups and spending years sabotaging democratic accountability and dragging his feet over the introduction of multipartyism. Also that he was complicit in the current military shambles. Former aides I interviewed recounted how, in his later years, a coup-wary Mobutu used ethnic recruitment and divide-and-rule to prevent consensus among key generals, destroying the nation’s defense system in the process. It’s clear today that the country has never recovered from this experience.

“Opinion is definitely mixed,” muses Pascal Bamanayi Kambala, a journalist with Congo’s B-one TV network, as he examines one of Mobutu’s velvet-upholstered thrones. “There are people who see him as a classic dictator and then there are Congolese who think he delivered national unity and prevented Balkanization. At the moment, the former tend to keep a discreet silence.”

The new Mobutu hero-worship extends – as is only fitting in Congo – to fashion, with some young Congolese men actually sporting the stiff-collared abacost jacket which Mobutu decreed should replace the “colonial” suit. A Congolese band called MPR (Musique Populaire de la Révolution, a cheeky reference to Mobutu’s former MPR ruling party) likes to kick off its music videos with a very convincing Mobutu lookalike addressing the nation.

The DRC is by no means the only African nation in the grips of rose-tinted nostalgia for a leader once reviled. On a visit to Uganda earlier this year, I was surprised to see, alongside election campaign posters for opposition candidate Bobi Wine, stickers of an older, burlier man plastered on lampposts and taxi-buses: Idi Amin.

A veteran Ugandan journalist I met insisted that Amin had been traduced. He said the leader who once dubbed himself “Lord of all the Beasts of the Earth and Fishes of the Seas” had served as a convenient scapegoat for racist British former colonial officers, and had in fact killed nothing like as many of his subjects as is widely believed.

That’s a view shared by Mahmood Mamdani, the father of New York’s new Mayor, who despite himself being expelled from Uganda by Amin in 1972, pays surprising tribute to him in Slow Poison, a recently published memoir.

The rehabilitation of Amin is even more curious in many ways than the revival of Mobutu. But public exasperation with Yoweri Museveni, who has been President since his rebel movement seized power in 1986 and is running for election yet again in January, has never been higher. With it is dismay at the prospect that Museveni, one of Africa’s canniest presidents, may plan to eventually hand the reins to his erratic son General Muhoozi Kainerugaba, chief of Uganda’s defense forces.

As with the DRC and Uganda, so with much of the rest of Africa. Across the continent regimes are being challenged as never before by Gen Z protests, staged by increasingly well-educated, aspirational young Africans who look around them and see substandard infrastructure, collapsing services, sharply rising prices and a shocking absence of opportunities and jobs. Their smartphones show them it doesn’t have to be this way.

In Kenya, protests by that demographic have rocked the administration of President William Ruto for the past year and a half; in Tanzania in October, young protesters were gunned down in their hundreds by security forces to push through a frankly unbelievable election result. Protests by counterparts triggered a military coup in Madagascar in October and have rocked administrations in Ghana and Mozambique this year.

Beyond the railings fencing off the neat lawns of Kinshasa’s National Museum lies the testing reality of daily life for the average Congolese citizen. Hundreds of city commuters wait by the roadside for taxi-buses in short supply, while Indian-made motorbike-taxis carrying entire families weave around potholes filled with filthy black water. The drainage ditches installed by Belgian colonial masters are choked with decaying clothes, plastic debris and thousands of discarded water bottles, picked over by storks.

Society’s inequalities remain as glaringly obvious as ever. Gleaming SUVs, their path cleared by shouting Congolese soldiers and bodyguards with walkie-talkies clutched to their ears, drive past at high speed, lights flashing. The ruling elite’s hangouts may have changed – it’s the Fleuve Congo Hotel these days rather than the Intercontinental and Paul Brasserie instead of the latter’s café – but they are still unaffordable to the average Congolese.

When Laurent Kabila’s rebel group marched down Kinshasa’s tree-lined avenues in 1997, watched by journalists like me, Gen Z’s parents expected radical change for the better. But while the DRC’s population has quintupled, the country remains one of the poorest in the world, with per capita annual income estimated at a pitiful $627.50, according to the World Bank. More than 78 percent of the population does not have access to electricity and the DRC has one of the highest rates of stunting in sub-Saharan Africa.

The newfound love for Mobutu is a de facto judgment on the current administration. “People say that in 28 years, it’s not as though anyone has done better than Mobutu,” said another journalist. “Look at Kinshasa today and what do you see? Dirt and chaos.” He decided, on reflection, not to give his name.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 22, 2025 World edition.