I heard a mental health professional suggesting that incarcerating young people would not be good for them, even if they had committed violent crimes. Apparently, their reasoning revolved around the brains of the young person not being developed enough to understand the context in which they find themselves. I groaned…

My journey into this part of life started at 20 years of age. I was asked if I wanted to go and help with a chaplaincy program at our local juvenile detention centre. It was so instructional for me, and I trust that it offered some insight and hope for the inmates (not much younger than me). I do remember meeting a couple of the ex-prisoners sometime later. They wished to express their gratitude for what they learnt by offering me ‘a real good Monaro, real cheap, up from Victoria’. That might be considered some partial success (and no, I did not take up the offer – and yes, we did have a ‘remedial’ session there on the footpath).

But during my time inside with these young men, I was quickly disabused that they were not making personal moral choices as part of the events that led to them being behind ‘the wall’ (which did have their close focus for much of their time inside). The reasoning might have been different for the individual inmates, although certain themes did emerge for some of them.

Yet within each of their contexts, the great majority of those inside knew they were (a) breaking the law at the time of their actions; and (b) that they were taking definite risks. That is, on average, they understood the reasons why they were put into a junior prison with reference to their actions.

This line of ‘choices – evaluating risk – making a decision (based on whatever reason) – acting illegally – being caught – imprisoned’ was thus clear to the great majority of these adult minors. They might have disagreed with their imprisonment, but they understood why it happened.

However, such an exercise of free-will decision-making does not sit well with many of the current therapeutic elites.

They therefore dismiss the role of implementing consequences that involve physical restraint because they believe these youngsters are simply acting according to their ‘Nature and Nurture’. That is, these purveyors of ‘they can’t help it’ thinking believe that the youngsters’ physical capacities they have inherited (including any predispositions they can guess at) in combination with their social upbringing and current context, fully define who they are. So, how could they possibly be responsible for committing crimes, even if those crimes are repeated? Surely, this line of thinking goes, they are ‘simply’ the product of their genes and the social forces impinging upon them! Putting them ‘inside’ would only add another negative social context to their learning patterns.

What surprises me is that this goes against one of the most basic principles of psychology – that physical consequences are often helpful when reasoning fails.

That, of course, would be debated, depending which school of thought you operate from for your therapeutic decision-making. The behaviourists would probably agree with incarceration and would most likely take a better behavioural history sooner. Rational-emotive therapists would try to help identify irrational thinking – and implement safety boundaries when reason fails (and the boundaries would be therapeutic, not physical). Psychodynamic therapists (Freudians and like company) would most likely want to take a long time (unless they are ‘short structure’ believers) to dig into the mysterious world of ego, id, and superego – although they might be able to identify defence mechanisms first. Hypnotherapists may or may not be interested. And the post-modernists using critical identity theory would want to help these young folk understand where they rate on the ‘oppressor/oppressed’ ladder and have them respond accordingly. The largest group is probably the cognitive-behavioural therapy group, but they too are often caught, as they focus on feelings (poorly defined), thoughts (poorly defined) and actions, within the Nature + Nurture myth.

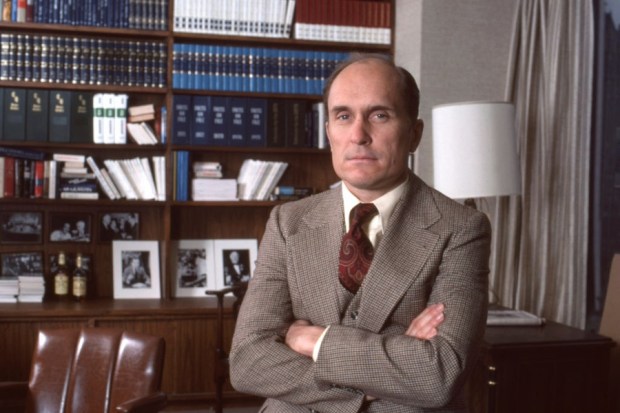

This conflict is not new. Thomas Szasz warned of it over 50 years ago. His basic thesis was that if psychiatrists confused moral questions with physical causes, they would become an awkward, uncomfortable and ineffective mash of medical specialist and pretend priest.

Dr Ron King, a past president of the Australian Psychology Society, warned of the problem in the 1980s. He was essentially ignored. Although, based on his thinking (and some others at the time), I did read another important volume in the history of this blight – Paul Kline’s 1988 Psychology Exposed: Or the Emperor’s New Clothes. Here was one Kline’s insights which took me on a line of investigation that has lasted decades:

I have shown how the scientific method is not, as defined by one the world’s leading practitioners, apparently well suited to the subject matter of psychology which is conceptually different from that of the natural sciences. Of course man [generic] can be described in terms of biochemistry, or anatomy, but this is clearly not psychology … [this scientific method emphasis] encourages work that is essentially trivial but correct and technically faultless.

So yes, when a therapeutic researcher or practitioner says, ‘So and so’s brain has not finished development…’ There will be a technical kernel of truth in that. But in the total picture of life and growing up, it is trivial. It is inconsequential.

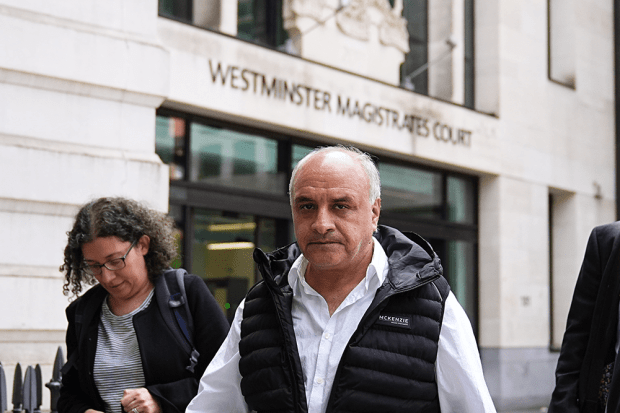

Theodore Dalrymple (a pseudonym) monitored the impact of this mistake in the British psychiatric system from within their prison and court systems. He has documented many cases (in his The Knife Went In and Admirable Evasions) where criminals were treated differently because they pleaded along the lines of ‘my harsh childhood and current situation’ made me do it – for example, a woman who took months to systematically poison her child to death was found guilty of manslaughter rather than murder.

Dalrymple uses these examples to explain why recent decades of psychological thought have been ‘overwhelmingly negative’. He believes the collective thinking presumes a confidence that is not real with reference to who we are as human beings. The consequence is that too many modern therapists make themselves increasingly inconsequential to the realities facing humanity, because their thinking ‘encourages the evasion of responsibility’. Without acknowledging human self-consciousness that enables moral choices, Dalrymple believes that contemporary therapy, ‘Makes shallow the human character because it discourages genuine self-examination and self-knowledge. It is ultimately sentimental and promotes the grossest self-pity, for it makes everyone (apart from scapegoats) victims of their own behaviour…’

Even more recently, Abigail Shrier (Bad Therapy) elucidates one of the outcomes of parents evading training their children in personal morality over the last decade: ‘Instead of using moral language to describe misbehaviour, educated parents had begun employing therapeutic language … agency slunk out the back door.’

This is why I groan when I hear therapeutic part-truths being promoted as bases for decision-making. The sadness, and perhaps perversion of it all, is that in trying to sound important, the opinions being promoted are ultimately based on self-defeating assumptions. As Kline said all those decades ago:

‘Until the voice is heard throughout the land proclaiming that the glorious colours of experimental psychology are but the emperor’s new clothes, there will be no progress and psychology will remain a quasi-scientific form of hermeneutics of interest only to its practitioners.’

What worries me is when, unlike Kline’s predictions, powerful people become part of the line cheering on the psychological emperor – then you know the ‘science’ is in their pocket.