Across history, the middle classes have dreamed of saving their societies. They see themselves as the sober conscience of the nation, humane, rational, on the right side of history. Yet their crusades often end not in redemption but in futility or betrayal, leaving others to pay the price.

From the German clerks and shopkeepers who embraced Hitler as a bulwark against chaos, to Iranian students who helped topple the Shah only to face Khomeini’s repression, the pattern is familiar.

Ordinary people provide the muscle; the middle class supplies the slogans. When the dream turns sour, they disown it and move on.

The same reflex survives in comfortable democracies.

In the late 20th Century, it found its home in the bureaucracy, the media, and the professions, among those who live by words and values more than by risk or labour. Their causes vary, but the posture remains: the enlightened rescuing the ignorant.

Climate, gender, race, refugees, each new campaign arrives clothed in virtue and paid for by someone else.

Australia offers its own examples. In energy policy, governments have spent tens of billions to produce an effect on global temperature measured in thousandths of a degree.

The rewards? Solar rebates, EV discounts, green-job contracts, flow to the well-heeled suburbs.

The costs? Higher power bills, shuttered workshops, job losses, fall on the working poor who cannot absorb them.

This week’s modelling shows average power bills rising again next quarter, yet ministers continue speaking of ‘transition justice’ while families ration heating.

We saw it with the Voice. Australians voted ‘No’, clearly and constitutionally, yet political elites immediately sought to revive it by the back door, through state treaties, departmental programs, and symbolic declarations. The people spoke; the government kept talking. It was less a reckoning than a reminder that in Australia, consent is optional for those who govern. The recent ‘nation-building treaty dialogues’ announced in WA and SA simply confirm it.

We saw it again in the official response to the grooming-gang scandals in Britain and Australia, where authorities silenced victims rather than risk puncturing the fantasy of multicultural harmony.

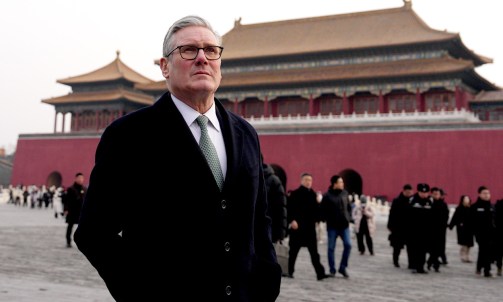

And now, in 2025, Cabinets in Britain, Canada, and Australia recognise a Palestinian state without referendum or mandate, as though foreign policy were the private conscience of the governing class rather than the will of the people they serve. In Parliament, MPs spoke of the recognition as a ‘moral duty’ yet never explained why the public had no say.

The middle class performs these gestures for reasons both flattering and cowardly.

Moral vanity plays its part; appearing compassionate matters more than achieving results. Insulation helps; a secure job and a distant postcode cushion them from consequences. And cowardice completes the trinity; to admit error is to forfeit status, so mistakes are hidden behind jargon, committees, and reports.

The result is not oppression in the old sense but a subtler disenfranchisement.

Whole swathes of the electorate feel decisions are made somewhere else, by people who will never meet the outcomes of their own ideals. The tradesman paying inflated power bills does not share the moral glow of the policy analyst who designed them. The nurse whose hours are cut to fund a new sustainability unit cannot applaud the righteousness that demanded it. And the families now queuing for rental inspections do not experience migration policy as a virtue, but as a cost.

Australia is often told that race is its great divide. In truth, it is class, not the Marxist kind, but the divide between those who imagine policy and those who endure it.

Who pays the power bill and feels it. Who loses work when a factory closes. Who walks home through the suburbs the idealists only drive past.

This pattern will not vanish through outrage or revolution. It can only be tempered by consent, by giving the public a direct say before grand projects are unleashed in their name. Direct democracy is not mob rule; it is a safety valve. When parliaments become insulated from consequence, referenda and citizen initiatives restore humility to power. They slow the rush of moral enthusiasm and force politicians to persuade rather than proclaim.

Switzerland, California, and several European nations have long allowed citizens to veto or propose laws directly. The result is not chaos but caution. Governments think harder before spending billions or curbing liberties. Australia’s own referenda tradition, though rare, shows that when asked plainly, people can judge complex issues with common sense unmatched by committees.

If every major ideological commitment, from energy transitions to treaty recognitions, required a vote of the people, politics would regain a forgotten virtue: accountability. No Cabinet could assume permanent consent. No moral cause could become law without proving its worth beyond the class that conceived it.

The truth is simple. Australia does not suffer from a lack of ideals. It suffers from a lack of permission. The governing class speaks of progress, but it rarely asks whether the public wants it. That silence is treated as assent. It is not.

Direct democracy would change the incentives. It would force politicians to argue their case in daylight rather than smuggle it through committees. It would make elites justify not only their intentions but their outcomes. Above all, it would protect the people who live with the consequences from those who merely applaud them.

The dream of saving the world will never fade. The urge to command it should. Conscience without consent is not virtue. It is vanity armed with power.

Salvation will not come from grand visions or moral performances. It begins with something older and humbler. It begins with asking the people first.