The fact that the eminent Irish actor Stephen Rea is doing Beckett’s Krapp’s Last Tape at the Adelaide Festival from 27 February to 8 March is a reminder of the Irish playwright’s centrality to modern drama. It’s true that his dream team duo to play Vladimir and Estragon in Waiting for Godot was Marlon Brando and Buster Keaton. And it’s also true that an equally distinguished British pair – Alec Guinness and Ralph Richardson – were considering doing Godot until John Gielgud to his consequent shame dismissed the play as a ‘dreadful load of old rubbish’. Still, it was done by Barry Humphries (with Peter O’Shaughnessy) in 1957 and Geoffrey Rush and Mel Gibson did it at Nida in 1979.

If you wanted a more classical production, less of a clownfest, there was the beautifully modulated Godot of Ian McKellen and Roger Rees.

And if Waiting for Godot tends to take the prize for the twentieth century’s greatest play – nevermind the witty trickster who will declare, ‘Wrong! The Cherry Orchard,’ – it’s worth remembering that everything Beckett did shows his genius. Happy Days gave us Dame Peggy Ashcroft up to her neck in sand (to wonderful effect) and quite late in the piece you could see at Fitzroy’s Universal Theatre the great Billie Whitelaw do Rockaby and Footfalls: you didn’t have to be a fan of this nearly terminal quasi-abstract theatre to know that you were in the hands of a master of cadence and dramatic spectacle. Never mind that the French gave him the Croix de Guerre for his work for the French Resistance and much of his most-famous play consisted – hauntingly and suggestively – of waiting for mysterious strangers.

Besides, there is that other Beckett masterpiece that has a centrality to the twentieth century that rivals Godot. Think of Patrick Magee – the sepulchral saturnine voice that asks, ‘More wine?’ in the torture scene from Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange – who was also Peter Brook’s de Sade in Marat/Sade. He was the original Ham in the first English language production of Endgame who asked Beckett in rehearsal, ‘What’s Ham like, Sam?’ And the ever cunning, ever down-to-earth voice replied with characteristic tact, ‘Just like you, Pat. Just like you.’

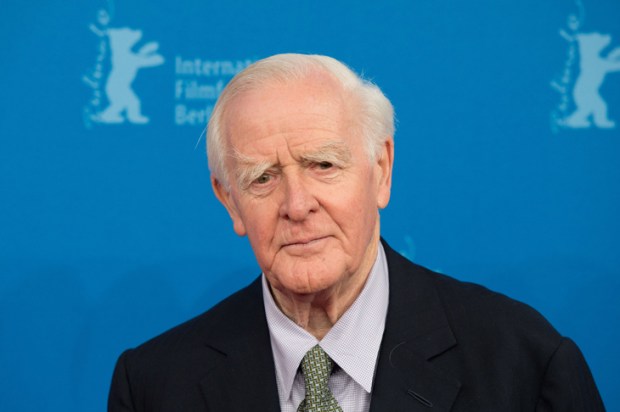

Stephen Rea as a young man played Clov in Endgame and he in fact took over from Jack MacGowran, that extraordinary comic actor who asked Beckett to give him a particular painting by the great Irish painter Jack Yeats. Beckett did and then MacGowran sold it. Beckett – characteristically – then bought it back.

But to play Clov after Jack MacGowran was to fill immense shoes and it would be natural for Stephen Rea (who is now 78) to think he was young for the part. But he is one of the great Irish actors. You can get hold of a recording of him reading ‘The Dead’ which a lot of people think is the greatest of the stories in Joyce’s Dubliners which it concludes.

In the 1970s he played Konstantin in Chekhov’s The Seagull to the Arkadina of Australia’s Zoe Caldwell with a supporting cast that included Michael Gambon and the very great Irish actor, Cyril Cusack. The BBC put it in their boxed set of Chekhov and you’ll no doubt find it on YouTube. Stephen Rea can be found in every kind of film and variety of television. He plays Richelieu in some Dumas epic with Catherine Deneuve, The Musketeer, and he’s a high and mighty dark lord in Maggie Gyllenhaal’s The Honourable Woman.

His most famous film is Neil Jordan’s The Crying Game where the background of the Irish troubles is the setting for a heartbreaking drama of sexual ambivalence and confusion. Rea acts like one of the archangels of his tribe. And this will almost certainly be true of Krapp’s Last Tape too. It’s a remarkable play which some baby boomers would have seen Elijah Moshinsky’s production of at Monash in 1968 with Max Gillies. It’s the story of a man listening to and responding to the recording of what he once seemed to have made of his life.

All of this appertains to what we make of the history of art, dramatic and visual. There’s a show of Noel Counihan’s printmaking at the Geelong Gallery until 10 March and that should make his straight-forward – often plangently expressed – leftism and sense of the oppression of working people utterly clear and might illuminate the special status which that great historian of ideas and painting Bernard Smith gave to Counihan.

Then there’s the new Andrew Bovell play Song of First Desire which is being directed at Belvoir by Neil Armfield with Kerry Fox and Sarah Peirse in leading roles. The title derives from a poem by that great poet and dramatic genius Lorca. The Spanish title is Canción Del Primer Deseo. It sounds fascinating to have the shadow of the author of Blood Wedding in the context of Bovell who wrote Lantana and The Secret River. The play encompasses Franco’s reign of oppression after he won the Spanish Civil War together with the ‘pact of forgetting’ in which – in the wake of Franco’s death – the bitter internecine antagonism of the two sides was, by mutual agreement, allowed to lapse. Bovell’s play was originally staged by the Madrid-based company Numero Uno Collective and cast members of the Belvoir production include Jorge Muriel and Borja Maestre.

Bovell is one of our most versatile and cosmopolitan playwrights. Things I Know to be True is being adapted for a film with Nicole Kidman. And his Spanish play sounds like just the kind of endeavour Armfield might illuminate. There was a period when he was fascinated by the great plays of the Spanish dramatic renaissance. A work like Lope de Vega’s Fuente Ovejuna is contemporary with Shakespeare while Calderón’s Life is a Dream (translated by Fitzgerald of Omar Khayyam fame) is contemporary with Racine. Part of the fascination of presenting the Spanish dramatic classics is to hear them in more or less modern English when the original has such grandeur.

It’s strange in a world which contains such wonders that Robyn Nevin, a woman who is capable of transforming any classical or modern work, should be directing Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None. She did the greatest production of Ray Lawler’s The Summer of the Seventeenth Doll anyone who saw it would ever expect to see. She’s a woman who believes in a national theatre and no doubt she will be crisp and expert faced with Agatha.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.