Of Boys and Men is a comprehensive, if not complete, portrayal of the plight of boys and men in the US today. In education, American boys are less ready to start school than girls; and apart from a slight advantage in mathematics, males fall further behind across the grades, and fewer graduate from high school. More men drop out from higher education and women attain 57 per cent of bachelor’s degrees and 60 per cent of master’s and associate’s degrees. The true situation in employment is obscured by references to the gender pay gap (which tends to disappear when work preferences, and mothers opting out of the workforce, are taken into account), and by the fact that an elite group of high-earning men and women has arisen in the market place as the real wages of most men have been dropping. With automation and trade deals, the availability of traditional male jobs has continued to decline. But as well, there have been progressive reductions in male participation in teaching, social work, and health, where there were fewer men to lose from the outset. Many males are now working fewer hours, and for a lower wage rate; and those that find it hardest to get a job are 25-34 year-olds. A third area of potential peril for men that is identified by the author is family life, where the growing economic independence of women has meant an increasing sense of dislocation from the traditional provider role for some strata of men. According to Richard Reeves, ‘While the role of mothers has been modernised almost beyond recognition, fatherhood remains stuck in the past.’

A puzzling aspect of the situation for males in the US is that only a few of the limited number of special provisions that are made available to them actually benefit them. For instance, in education, vocationally oriented programs and institutions are one of the rare standout successes. Reeves surmises that ‘motivation and aspiration … are a big part of the story here’, and in contrast to women, modern-day men seem to be showing less independence, planning, and persistence. But there is also a larger, structural context to the impasse which the author describes as ‘the centrifugal dynamic of culture-war politics’. The political Left is said to be to blame for its adherence to a characterisation of ‘toxic masculinity’, its attribution of societal trends to personal failings in males, its denial of the biological basis for sex differences, and a refusal to accept that gender inequalities can also apply to boys and men. As a counterpoint, the political Right is accused of promoting populist, traditional stereotypes of masculinity and femininity; and justifying biological explanations of gender differences and inequalities that are ‘just too thin to bear the weight they put on them’. Hence, there exists a maelstrom of claims and repudiation, that has individual and social costs, and which disallows positive and constructive solutions.

The description of the two opposing political positions demonstrates that biology is a central issue in any discussion of the problems of boys and men, and that ‘understanding the role of biology is necessary for keeping it in its place’. And then, possibly at the risk of being branded as reductive or engaging in ‘sex essentialism’, evidence is presented that women are generally more agreeable and conscientious, and more people-oriented and nurturing; and that men are often more aggressive, risk-taking, status-conscious, and driven by sex. The caveats are that the statistical distributions overlap, and they are likely to be only really telling at the tails of the curves; that sex differences are ‘magnified or muted by culture’; that such differences have ‘a rather modest impact on day-today lives in the 21st Century’; and that average differences do not justify gender inequality. The best-qualified person should always be appointed to a job; but group differences should be acknowledged nonetheless, and they are the reason that gender parity in all fields of endeavour is likely to prove elusive. As it happens, the more pressing biological issue between the sexes could be the fact that boys’ brains develop more slowly than girls’ brains, and this probably has significance throughout childhood, the teenage years, and into emerging adulthood. At secondary school, general neural immaturity may make learning harder for males. Moreover, the relative two-year delay in adolescence in the maturation of the frontal cortex will likely influence the abilities of male youth to exercise restraint and to make good choices.

It is interesting that Jonathan Haidt, who is the author of The Anxious Generation, which is the landmark book on the effects of the digital world on Gen Z, also references his argument to brain development, and this may represent a trend in discussions about gender effects. More particularly, Haidt’s book is instanced here because it discusses Of Boys and Men, and it suggests that Reeves could have extended his examination of psychological influences on males to include the impact of smartphones and online gaming, which has transpired alongside the evolution of safetyism in parenting. Haidt asserts that many boys have been ‘swallowed whole’ by multiple internet-connected devices, and the hours that they devote to them each day represent both ‘an escape from an increasingly hostile world’ and striving for gender-related personal agency. Safetyism is parental coddling and over-protection, which contrasts with the care-giving of previous times, and which allowed children to walk to school alone, play outside at night in summer, and engage in other autonomous activities. It is perhaps significant that in Japan they now have a term (hikikomori) for sons who are secluded in their bedrooms with screens, and who are incapable of launching into education, employment, or training.

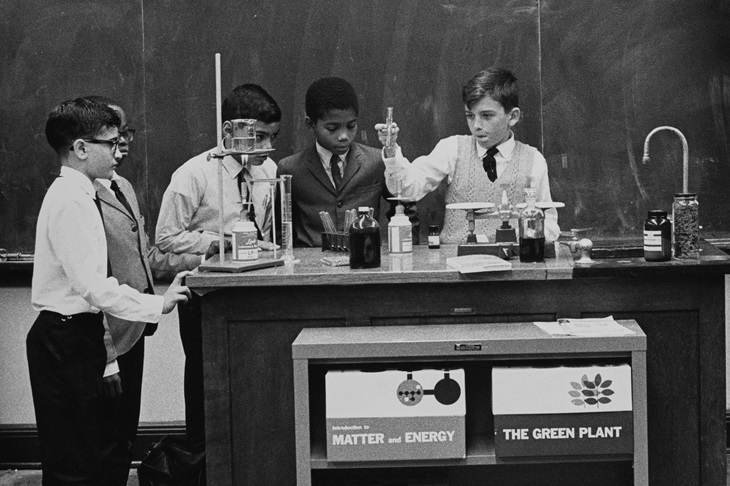

What does the book suggest should be done in each of the areas of education, employment, and fatherhood? Firstly, in a community where ‘he’s a boy’ can be a shorthand explanation of the failings of male students, schooling needs to become ‘more male-friendly’. But, in addition to attitudinal change, the author argues for boys to regularly have an extra year before school to catch up on the developmental advantage that girls have. Two other educational recommendations are to have more male teachers and a substantial expansion of career and technical education. Right now, all young people should be advised that by 2030 there will be more than three times the new jobs in Health, Education, Administration, and Literacy (the acronym HEAL is suggested) than in STEM areas; and men could be assisted into these expanding occupations by rebranding them, and by building a pipeline to them through education accompanied by financial incentives. Reeves notes that there are presently labour shortages in both teaching and nursing, and ‘we are trying to solve them with only half the workforce’. However, the author’s most bold proposals could relate to the traditional role of men in the family which he sees as unfit for a new world of gender equality. Caring needs to be more completely shared, and it needs to be formally recognised that the father and mother each have unique contributions to care-giving. Shared-care should be supported by paid leave for fathers for six months, equal custody after a separation, and many more workplaces that are friendly to fathers and to families.

The contributions Of Boys and Men are that it considers the situation of males in society from three interrelated perspectives, it argues for equitable gender provisions to be extended to boys and men, and it has parallels and lessons for Australia and New Zealand. Reeves enters a debate where some may fear to venture, and he does so with balance, and with a commitment to the good outcomes that are possible for everybody when boys and men have better lives. Nevertheless, as has been shown, this book is not a complete account of the current situation for males. Other psychological topics that might have received more attention are the antecedents of the staggeringly disproportionate numbers of men in criminal justice systems, and the shocking prevalence of male ‘deaths of despair’ from alcohol-related illnesses, drug overdoses, and suicides. Further, this discussion could conceivably have expanded on his allusions to the 1937 publication of John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men, as it is a timeless study of male friendship, and of isolation and powerlessness, in challenging circumstances. Again, Haidt, in The Anxious Generation, discusses the issue of male disconnection and anomie, and he observes that boys have their best friendships in teams. Perhaps we should be concerned that the contemporary every-man has now lost almost all of his male-only spaces of lodges, service clubs, unions, bars, and veterans’ associations. The ultimate worry that Reeves voices in Of Boys and Men is that many more males ‘will look elsewhere’ and possibly seek connection and solace in manosphere chat rooms (such as Men Going Their Own Way) where radical separatism can flourish.

References

Haidt, J. (2024). The anxious generation: How the great rewiring of childhood is causing an epidemic of mental illness. Allen Lane.

Steinbeck, J. (2024). Of mice and men. Penguin. (Original work published 1937)

Peter Stanley is a retired psychologist and university lecturer