The recent sci-fi movie Paradise Hills delivered one gem for this viewer; the choristers’ white ruffs setting off each young woman’s face were a reminder of another age, when clothing was designed to flatter the wearer. Ruffs, such as those worn by Elizabeth 1, are a ‘crimped or pleated collar or frill, usually wide and full’, and they have the charming effect of framing the face, just as petals frame a daisy’s centre.

By contrast, clothing in our era is utilitarian and minimalistic, designed for comfort and ease but not to delight the eye. Take the crew neck, a 1930s creation drawn from sweaters worn by US rowers or oarsmen. In 1942, influential pattern designer and ‘Dress Doctor’ Harriet Pepin described the crew neck as ‘utilitarian, characterless, monotonous and badly proportioned’; any other neckline was to be preferred. It was the only neckline worn by a man in a 1937 fashion dictionary, historian Linda Przybyszewski reports in her 2014 bestseller The Lost Art of Dress, which is a cri de coeur for the bygone elegance of 1930s-1950s America. Despite doing favours for few bodies, crew necks are now ubiquitous. The sagging crew neck is especially unattractive on men over a certain age, lending a Jabba the Hutt silhouette to any overnutritioned body.

It is not only necklines. We have managed practicality but not beauty with our jeans, trackies, hoodies, leggings, and tee shirts. Nor do mirrors or irons seem to be widely available, judging by appearances. Clothes have never been so cheap, the average wardrobe so expansive, the average consumer offered so much choice, with the resultant overall effect so scruffy and disappointing. It is a commonplace to remark, after watching old newsreels and movies from the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s, how well dressed (not to mention thin) Westerners used to be. Ironed shirts, belts, hats, jackets, heels, full skirts! In previous eras, when clothes were scarcer and so much more expensive, we gave them more care and attention, and wore them with pride; now that they are cheap and abundant, we no longer prize them. Young Australians can have no idea how costly clothes used to be, and how few we all had, when each garment had to be handmade from scratch and we all had but one outfit for ‘Sunday Best’. In Japan, feudal communities never tossed away worn and ripped clothing, but repeatedly mended the precious, usually indigo, pieces, developing the tradition of sashiko, now a decorative embroidery in its own right. In lawyer Kevin Stroud’s History of English podcast, he refers to an actor in 1599 buying a velvet cloak that cost ‘the equivalent of a schoolmaster’s salary for an entire year’. Costumes from deceased aristocrats were bequeathed to theatres and could cost more than staging an entire production.

Now, we have China, where 24/7 factories pump out a torrent of thoughtlessly constructed and cheaply made garments with unfinished seams and loose threads, destined for a brief moment in the sun on someone’s back, before re-entering the torrent of rag, and ending up in op shops or landfill or poor countries. We want things that don’t require ironing or hand laundering, give us easy-care please. And stretchy, for our expanding waistlines. I have a relative who won’t buy anything that needs ironing, which rules out all woven, natural fabric.

This degradation stems back to the mid-20th century, when our buildings too became victims of the same ideological fashion for deconstructing the West’s traditions. In came functionality, minimalism and practicality, out went decoration, tradition and formality. Modernist architect Le Corbusier famously described buildings as ‘machines for living’ and the result was sweeps of collectivist high-rise concrete boxes rimming modern cities. We are in the sartorial equivalent to these concrete blocks, wearing functional and dull ‘uniforms for living’, to paraphrase le Corbusier, which are nothing like the decorated and highly worked tailored pieces of before. Entire categories of decoration and stitching have all but vanished: lace, braid and ribbon trims, the thousand and one joys of hand embroidery such as French roses and blanket stitch, piping and grosgrain edgings, darts, inserts, French seams, hats, detachable collars and cuffs, furbelows… so many highly developed and creative ways with fabric have been lost to the over-efficient cutters and stitchers of China.

Does it matter? Who cares what we wear in public? I am generalising grossly, and of course no one cares about my dress expectations. And it is an undoubted advance that all can now easily afford to be clad. But we are social creatures and clothing carries cultural connotations. If we don’t take care of how we present ourselves, what will we care about? Ugliness lowers everything in its orbit, just as beauty raises it. We don’t wear shabby sweats to a job interview (if we want the job) or to meet a partner’s parents. We don’t walk around half-naked, the pitiful antics of Kanye West’s new wife Bianca Censori notwithstanding. Tattoos, Goth make-up, hippie homespun, three-piece suits and ties, we recognise this language even if we don’t talk about it. Clothing inevitably makes a statement, which is why so many fashion designers wear Steve Jobs-style all black as they take a bow after the show – they want their clothes to do the talking, not their own tastes. We all swim in the same stream, so if we wear dull clothing with little attempt to make the best of ourselves, we dispirit those around us, giving them permission to laze about too. As Admiral McRaven who wrote Make your Bed realised, improvement starts with the little things.

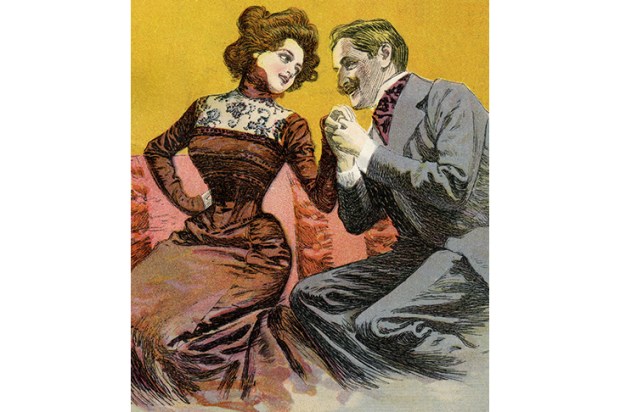

Pockets of excellence remain: individuals such as Iris Apfel can be inspirational, expert tailoring endures, money can still buy quality, niche websites fly the flag for the well-groomed, and young women particularly have an unquenchable passion for looking their best. X occasionally serves up a video taken from behind an expertly put-together young woman, wearing a waisted dress with full skirt, heels, hat and gloves, as she sashays through the streets of a European city. The seas of people part before her, men of all ages gape in admiration, and teenage girls in sweats stare in envy. We all recognise excellence when we see it. If only we could bring ourselves to display it more often.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.