If asked to think about food preservation for a moment you might picture an aproned woman boiling oranges for marmalade in a large copper maslin pan; or vegetable scraps being turned into stock; or those recipes from wartime rationing using root veg in place of sugar; or even, with an eye to the modern, you might imagine a trendy chef preparing offal in a gleaming chrome kitchen to ensure the nose-to-tail credentials of his restaurant.

Some of the attempts in the past to spin out the life of fresh produce sound positively disgusting

But there is more to the history of preservation than preserves, and the obvious enemy, when we talk about preservation, is waste – the two engaged in a constant battle. Exploring that battleground is Leftovers, the debut book from Eleanor Barnett, a food historian and academic.

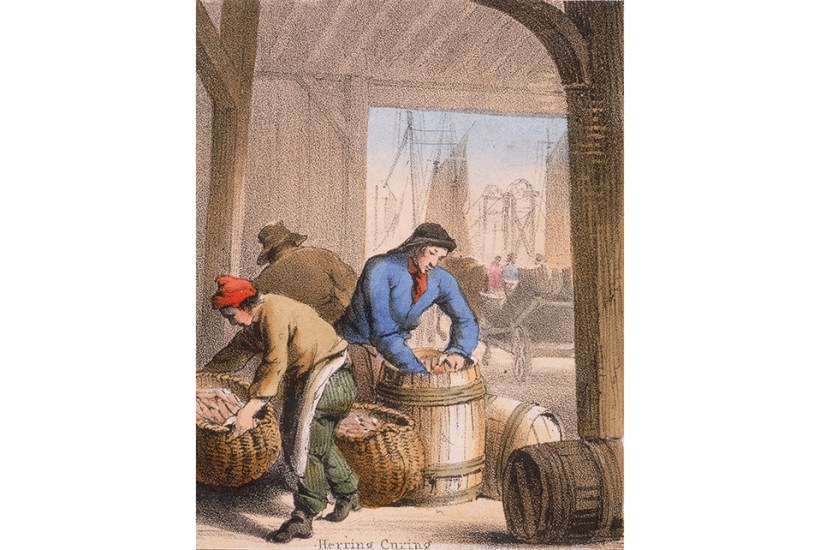

The premise is simple: ‘From the moment food is harvested or slaughtered, it risks becoming inedible as it begins to ferment, rot and decompose.’ Our ability to prolong the life of these perishable items has influenced the course of history. Leftovers tracks that history – with a particular focus on Britain – from the time we left behind a nomadic lifestyle to the American revolution (where Barnett frames the dumping of tea leaves as food waste) and the military invention of the tin can.

Of course, the history of food waste is also the history of poverty, and is therefore informed by our changing morals and priorities, and how we view that poverty. As Barnett puts it: ‘If, as the old adage goes, “you are what you eat”, we – our values and culture – are equally defined but what we don’t eat.’ Leftovers charts that division of poverty and wealth, and how it was affected by early fly-tipping, Victorian hygiene concerns, the Industrial Revolution, the rise of the domestic cookbook and advances in science, technology and public health.

Of course, home preservation and culinary ingenuity do feature, and Barnett is particularly good on the domestic lives of ordinary people in the past. She describes the moral panic that motivated local authorities to prevent pig ownership; the day-to-day trade of the rag-and-bone men; and how, with the guidance of Mrs Beeton, a home cook could zhuzh up tinned meat into a stylish soup. But she avoids the obvious and nostalgic. Indeed, some of the attempts to spin out the life of fresh produce sound positively disgusting. Hannah Glasse’s solution to potted birds which ‘smell so bad, that nobody could bear the smell for the rankness’ is just to wash off the rancid butter and start again.

Leftovers is certainly no rose-tinted account of how Britain made do and mended in the good old days but is now profligate, and ignorant of traditional preservation techniques. On the contrary, it doesn’t shy away from the more difficult moments in history: food poisoning, enormous waste as a direct result of unsuccessful preservation and even government-mandated starvation of whole communities.

It is ironic that the technology that has brought about the ability to preserve food better has in fact increased our propensity for waste. Long-life produce implicitly discourages domestic recycling and preservation; our reliance on best-before dates has led to undue cautiousness, which results in us throwing things away unnecessarily; and the global cold chain has meant that we have near-constant access to any product in any season from anywhere in the world. Only when true crises occur (such as Brexit and Covid), and supply chains are interrupted, do we realise how susceptible we all are to food insecurity.

It is here that Leftovers feels especially timely. Wasting food has always been a ‘morally-charged issue’, Barnett writes. Our reasons for attempting to reduce food waste may have changed from the religiously focused preservation of God’s creations to climate-crisis-informed environmental concerns. But of course there is nothing new under the sun. Barnett tells us: ‘Our exploration of food wastage in the early modern period has revealed a society deeply divided, and strictly structured by economic class.’ You could say the same about food inequality in modern Britain. The statistics Barnett presents of those living in food poverty are shocking. In July 2020, nearly one in four 16-to-24-year-olds in Britain were resorting to using food banks. The global environmental goals missed by governments make for bleak reading.

But Barnett leaves us with reasons to feel optimistic. While state intervention is required for systemic change, the role of the consumer is more powerful than ever, and she is able to point to encouraging examples of both food justice groups and customer pressure leading to businesses and industries actively changing how they handle their waste. For better or worse, Leftovers is more than a historical retrospective; it is a book for our time.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in