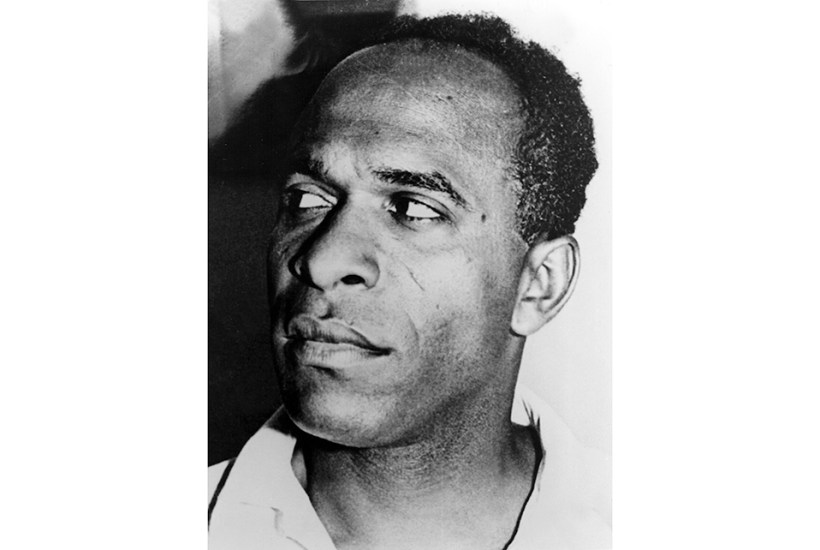

‘If I’d died in my thirties, what would be left behind?’ is the question that keeps coming to mind reading this timely new biography of Frantz Fanon, the psychiatrist and philosopher who became an icon to leftist revolutionaries across the globe. ‘Would I want history to judge me by what I wrote at 36?’ For that was the absurdly young age at which Fanon died of leukaemia in 1961, leaving two key works to his name: Black Skin, White Masks and The Wretched of the Earth.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in