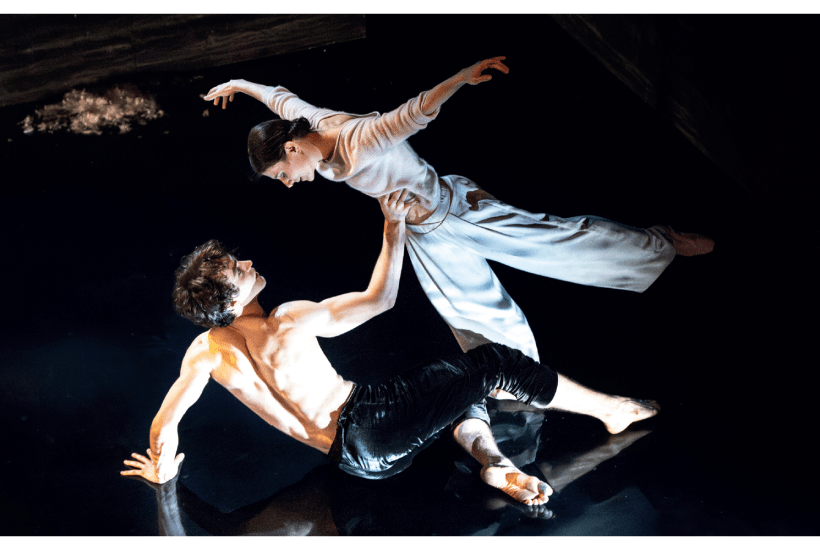

Literate, thoughtful and serious, Kim Brandstrup ranks as one of the most honest and honourable of contemporary choreographers. A proper grown-up, scorning bad-boy sensationalism or visual gimmickry, he compensates in solid consistent craft for whatever he may lack in striking originality, and the double bill he presented earlier this month as part of Deborah Warner’s season in the chapel-like Ustinov Studio behind Bath’s Theatre Royal is quietly and characteristically satisfying.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in