I can dimly remember the internet getting going, gradually staking its claims on our attention with hardly anyone except tech nerds – and famously David Bowie – realising what was going on. In our defence it was the 1990s and we had a lot else to think about: Britpop, The End of History, lads’ mags, guacamole, supermodels, Tony Blair, Monica Lewinsky, etc.

But here we all are now, in a world where I can do my banking from bed, America is fragmenting like papier-mâché in the rain, and primary school children can get porn on their smartphones. Can anyone recall the incremental steps that brought us here?

If not, it might be time to listen to Jamie Bartlett’s The Gatekeepers, which seeks to trace how a small digital elite and their platforms came to decide what billions of us see and hear every day. The trajectory he describes is one from idealism to cynicism, from sharing to monetising, and -– for the bulk of users at least – from the promise of electronic liberation to something more akin to a complicated captivity.

The general impression is one

of feisty debate rather

than ponderous consensus

The first episode opens with a snatch of Donald Trump’s singsong voice floating out like that of a carnival mesmerist on 6 January 2021, telling his disgruntled supporters: ‘We’re going to the Ca-pi-tol…’ What followed involved the Capitol coming under attack for the first time since the burning of Washington in 1814. When Twitter executives saw hashtags such as #executemikepence trending, calling for the killing of the vice president, they began to panic. Two days later, Trump’s account was suspended: the medium which had helped radicalise an online population by opening a platform that was available to everyone was actively censoring one of its most famous users.

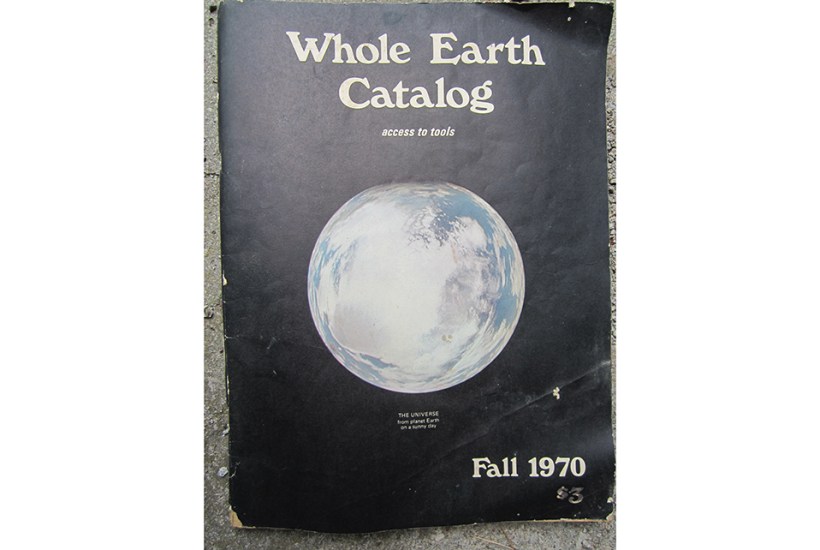

Bartlett asks one of the pioneers of the internet, Dr Larry Brilliant – yes, that is his real name – to explain ‘how we got from utopian vision to where we are now’. The earliest social network, of which he was a co-founder, grew out of the Whole Earth Catalog, a benign print bible for the Californian counterculture which focused on self-sufficiency tips and product reviews. The virtual community was called Well – the Whole Earth ’Lectronic Link – and Brilliant saw ‘magic happen’ on some of those early online conversations, where no one knew the gender, race or age of the person they were talking to, and up to 40 per cent of the revenue came from devotees of the Grateful Dead trying to source tickets to their shows. But the Well was a ‘small, self-selecting community’ that instinctively agreed on good behaviour. At a ‘ubiquitous’ scale, Brilliant says, everything changed, and ‘you see the best of humanity and the worst of humanity’.

One law was crucial to maintaining the internet’s freedom of expression, but at the cost of giving its worst elements room to expand. Section 230 of America’s 1996 Communications Decency Act fatefully declared that, unlike traditional publishers, digital companies could not be held liable for what users posted on their sites: the result has been a continuous explosion of content without responsibility. When one is in the thick of a phenomenon, as we are, it can be hard to discern its pathway, but I’m grateful to Bartlett for getting out his torch.

In the podcast Law and Disorder, three luminaries of the legal world – Helena Kennedy, Charlie Falconer and Nicholas Mostyn – review the news through a lawyer’s lens, thrashing issues out between them. I always enjoy hearing lawyers argue because the world is becoming ever more chaotically disputatious anyway – and at least they’re trained to do it properly.

The general impression is one of feisty debate rather than ponderous consensus. Indeed, Kennedy spends much of the first episode berating Falconer for changes he introduced to the role of Lord Chancellor when in government, effectively reducing it to a title attached to the Justice Secretary and making it possible for a non-lawyer to occupy the role for the first time. She has a point: in 2016 this resulted in the appointment to Lord Chancellor of Liz Truss, who didn’t seem to like lawyers very much at all. When the Daily Mail denounced three High Court judges as ‘Enemies of the People’ in 2016 for their ruling on Brexit procedure, Truss took a whole two days to stir herself to a tepid defence. It was a harbinger of things to come: as is noted in discussion, the chasm between politicians and lawyers is getting ever wider.

Yet while our legal system can be frustrating at times – not least because its necessary processes have long been starved of funding – it also represents the last recourse of an individual to protection against unfair or persecutory authorities. No one can accuse the trio here of avoiding contentious issues: the first few episodes range across the law in Gaza, the Rwanda Bill, and the Post Office scandal. Listeners will certainly leave the podcast better informed than when they started. They may also be more worried about Britain’s direction of travel./>

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in