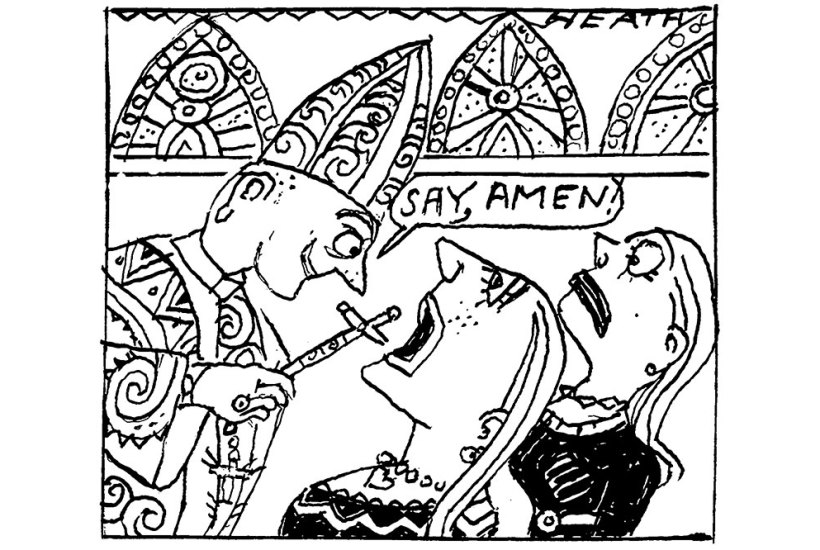

This Saturday, go to London’s oldest Catholic church, St Etheldreda’s in Ely Place, Holborn, and you will find a gathering of singers, along with actors, announcers and other public speakers, who have come to have their throats blessed. Two crossed candles are held up by the priest and either these or a piece of wick soaked in holy oil are touched to each kneeling suppliant, as a special prayer is said.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in