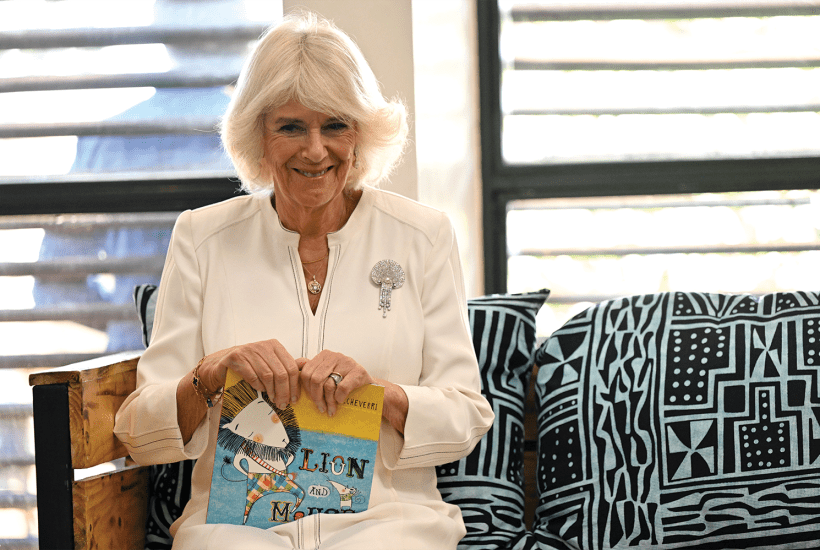

In the dog days of winter, when venturing out under darkened, sleety skies is to be avoided if at all possible, an online book club often seems the most appealing kind there is. Here in the UK, on territory in which the daytime TV hosts Richard and Judy once held undisputed reign, a bookish royal has entered the fray: Queen Camilla, whose ‘reading room’ and associated charity was launched on Instagram during the pandemic, and has now branched into podcasts.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Or

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in