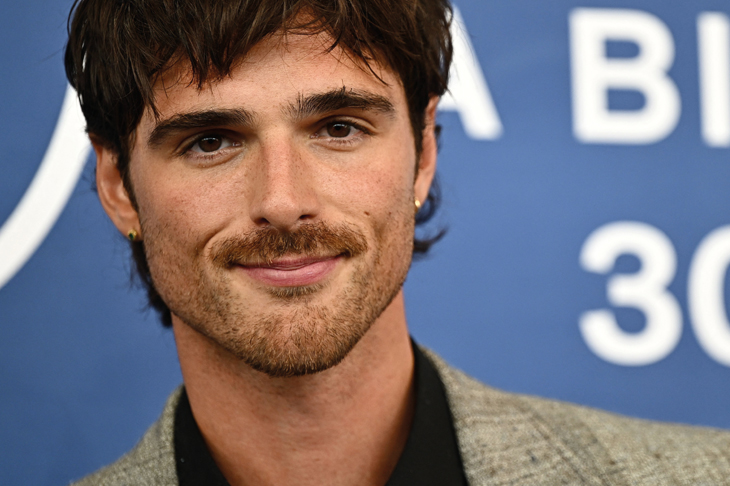

It’s the time of year when there’s a lot of talk about films and catching up with films. Along with this, there has been talk about a new young Australian star, Jacob Elordi, who plays Elvis Presley in Sofia Coppola’s Priscilla, and a young English toff in Saltburn. It’s hard to imagine that Coppola, who could make a film of genius like The Virgin Suicides from the Jeffrey Eugenides novel, wouldn’t put Elordi’s talent to significant use but we haven’t caught up with the film yet that started in cinemas on January 18.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Subscribe for just $2 a week

Try a month of The Spectator Australia absolutely free and without commitment. Not only that but – if you choose to continue – you’ll pay just $2 a week for your first year.

- Unlimited access to spectator.com.au and app

- The weekly edition on the Spectator Australia app

- Spectator podcasts and newsletters

- Full access to spectator.co.uk

Unlock this article

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in