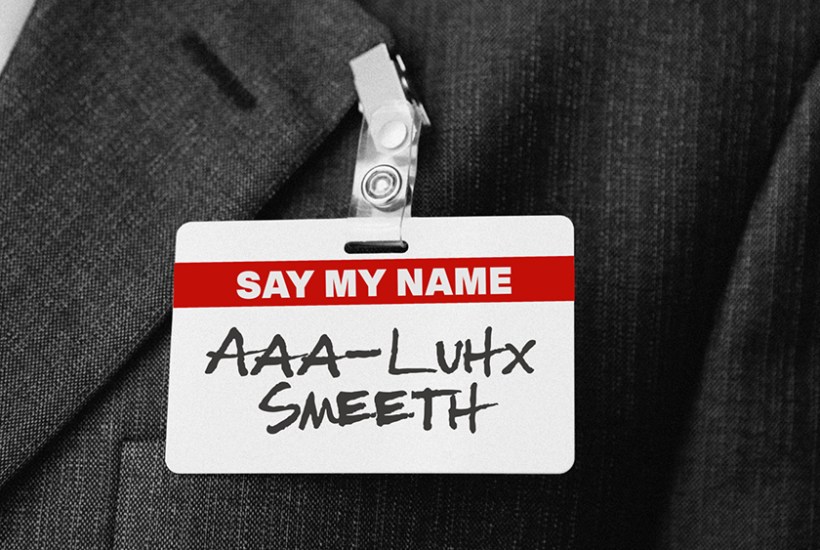

Just as Francis Maude was revealing his exciting plans for grand reform of the civil service, I received a message from a friend who once worked in Whitehall. In the subject field: ‘What fresh hell is this?’ Underneath, a screenshot of an email she’d just been sent by a civil servant. There was the name of the sender, Alex Smith, then underneath that another line: ‘SAY MY NAME: Aaa-Luhx Smeeth.’

My first thought was that Alex was taking the mick, making fun of people who couldn’t pronounce a simple name. Alex won’t be long in the job I thought. How wrong I was. It’s not just Alex. Great swaths of the civil service, I discover, have signed up to what’s known as the ‘Say My Name’ pledge – a commitment to include a phonetic guide to pronouncing your own name in every written communication.

I’m unsure quite how an audio name badge works. Do you press the other person’s? That seems intrusive

‘Our names are central to who we are as individuals, and getting people’s names right is crucial to helping people feel seen, included and valued,’ I read in Civil Service World, Whitehall’s in-house magazine. I also discovered that in 2021, when large parts of government were still refusing to leave home for fear of Covid, Defra nominated itself for an ‘enterprise award’ for ‘outstanding advancement’ for asking its staff to sign up to Say My Name. Pronouns are old hat. I’m in debt to Alex Smith for alerting me. Phonetic pronunciation is the new measure of real progress, which is why Lord Maude should keep a beady eye out for departments that deploy it, and mark them down as most especially in need of reform.

The Say My Name movement actually began in a reasonable fashion in America as part of the anti-racist business. African-American names are often mispronounced, so the theory goes, and so a phonetic guide spares people the need to constantly correct their colleagues. But it’s astonishing the speed with which ‘allies’ now co-opt – colonise, perhaps – the things devised for minority groups. Within a year, Say My Name had found its way into universities and institutions, both in America and the UK, where it swiftly became a code of conduct everyone must participate in – a test of loyalty.

‘I, X, do hereby affirm my commitment to the campaign and vow to state my phonetic spelling and to show respect to others’ names and to celebrate difference.’ This is a standard pledge form.

Bournemouth university students cleverly re-named it the ‘Say My Name Safety Pledge’ and wrapped up the issue of ethnic names with a trans person’s right to be called by their chosen trans name, which made pronunciation a matter not just of manners but of actual harm. ‘Being misgendered or dead-named in any setting can cause people to withdraw from situations and feel excluded from what is going on around them.’

Under the dotted signing line on the university name pledge form, the text reads: ‘I pledge’. Then in bold: ‘Do you?’ I admire the air of genuine threat, but they’ve missed a trick. If failing to take pronunciation seriously poses a real risk to the vulnerable, shouldn’t there be punishment for those who break the vow? Take note Bournemouth. There’s always room to grow.

Oh where’s the harm, you might ask. It’s just a little sinister fun. Let the children virtue–signal in their sign-offs. To an extent I agree. But civil servants aren’t students and they’re supposed to have better things to do than play politics in their bios. They should be clever enough to see – even to care – that a universal pledge to include phonetic spellings will have exactly the opposite effect to the one intended.

Take Alex Smith. He had no choice but to sign the pledge. The civil service had, after all, given themselves awards for adopting it and his boss was no doubt flushed with pride.

But what’s poor Alex to write? ‘Alex Smith’, followed by ‘SAY MY NAME: Alex Smith’? That would certainly mark him out as passive aggressive. He had no choice but to concoct something daft, which seems almost designed to deliberately fox any civil servant from outside the Anglosphere. If you think it feels uncomfortable to have someone mispronounce your name, imagine discovering that the colleague you’ve been calling Aaa-Luhx for a year is actually ‘Alex’.

The second casualty of Say My Name is time. I wish I could believe it was introduced on a whim, not an expensive, protracted process, but there’s little hope of that. Think weeks of meetings, steering groups, resolutions, amendments and so very many, many hours of taxpayer-funded time.

The Met Office, owned by the Department for Science, is full of enthusiasm about pronunciation, and in a list of its Diversity and Inclusion highlights for 2022-23 there is a detailed description of how they approached the process. First came an ‘Empathy Lab’, a three-day event for nearly 300 employees in partnership with something called ‘All Able’.

It’s a mistake to rush into something as significant as spelling, so no actual decision was made but a steering group was formed to ‘grow knowledge and skills of digital accessibility across the Met Office’. After an untold number of further meetings, the steering group has decided, cautiously, to introduce an ‘audio name badge’. I’m unsure quite how an audio name badge works. Do you press the other person’s? That seems intrusive. Do you proudly press your own at intervals in the office?

The most significant objection to an imported fad like Say My Name is that although it’s of no real use to civil servants, it’s extremely handy for any of their HR–minded overlords. It sorts the problematic dissenters from the agreeable compliant types in no time. It’s just a shame for the country that it’s the civil servants who have the guts not to sign up who are exactly the ones it needs most.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in