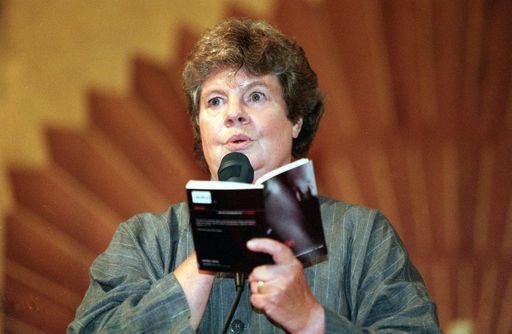

Dame Antonia Byatt, the novelist A.S. Byatt, has died after a long illness. With her goes part of the conscience of English fiction; its heart, its power to think, its capacity for feeling both wild and exact. She was one of the most generous people I ever knew.

One of the things you had to accept if you were a friend of Antonia’s was that she was interested in a lot of things that you knew nothing about. One of these, in my case, was sport. One day I dropped in on her in her house in Putney, and found her glued to the TV, bright, almost gleeful with attentiveness. I am so uninterested in any sport I can’t remember whether it was snooker or tennis, but I sat down and, when it seemed to be hitting a hiatus, mildly wondered what it was, exactly, about…

I experienced the privilege of her fond gaze and her warm, rigorous offers of ideas – more than I deserved

Antonia was amused. She could explain. It was an explanation of true splendour, an analytical intersection of aesthetics, science (ballistics, perhaps) and the revelation of an individual character through – what could it have been? – the movement of an arm and the choice of a style of stroke. It was glorious, seeing something of what Antonia saw. And then the second set began.

Antonia’s personality and mind were complex phenomena, with features rarely found together in a single person. She was immensely warm and kind, but somehow detached from the English tendency to bring everything back to a joke. She was very ready to forgive and overlook blunders, but judgement could come, too, complete and terrible. She valued the workings of the intellect, in extravagant play as well as in systemic analysis, and adored worldly, sensuous pleasures – colour and light, comfort, Veuve Clicquot, good chocolate, swimming.

Some of my most treasured memories of her aren’t of literary exchanges. There was the afternoon I took her to Liberty to introduce her to the genius of Issey Miyake’s pleated garments. Much of the English novel springs from writers brought up as non-conformists, and Antonia, who was brought up a Quaker, knew well how much sensuous rapture those austere minds could produce. One of her favourite sentences in fiction was that extraordinary line at the beginning of The Mill on the Floss: ‘I am in love with moistness.’

Her career took a time; her novels, rich, original, coherent but complex, needed serious engagement. She started publishing novels in the early 1960s, working as a university lecturer at the same time. She came from a very brilliant family, and for many years, the fact that Margaret Drabble was her more successful sister appeared impossible to escape. By the 1970s, her boldness ought to have been clear. The Virgin in the Garden, written in a period of appalling grief after the violent death of her 11-year old son Charles, is an extraordinary layering of history, myth, performance and violence. It didn’t make an immediate impact; but over the years, it sank in.

I met her at the absolute peak of her career, two or three years after she had published Possession, probably the most brilliant and thrilling of all her books. An extraordinary novel to take the world by storm – dazzlingly exact pastiches of Victorian poetry, a love letter to the pleasures of archival research, a constant flirtation with the most outré literary theory. But she had bent the world to her will. It was exactly the moment when most novelists happily retreat and enjoy the acclaim. Antonia went out, interested in what new writers were doing, carrying out public works – for years, she was a pillar of the British Council, the Royal Society of Literature and many other bodies, enduring inconvenience and boredom uncomplainingly, and lighting up at something new in the room, or on the page.

I felt the full force of this energy and interest from the moment she asked me to write a short story for an anthology. (It was about gays cruising on Hampstead Heath – she took it in her stride). She wanted to understand what you wanted to do, and she wanted to be interested. Interested by people different from herself.

Most of all I think she valued a moment when she couldn’t immediately account for a flash of readerly excitement. She liked being led to the new thing, by a writer just starting out, by a scientist or historian she’d just met, by (some of her favourite people) her translators. I loved her. Quite soon I realised one ought to limit one’s requests to her; she was so generous she would put her own comfort behind the hopes of other people. When I asked her how I could make the experience of my 50th birthday party tolerable to her, and, as an old friend, she said ‘No music – a comfortable chair in a quiet corner – a taxi – and some Veuve.’ I had anticipated all of it, but I did wonder just how much discomfort she had put herself through when people hadn’t asked.

I think all that a novelist can reasonably hope to achieve is to leave behind a solid body of work. Antonia did much more than that. She set a consistent example of intellectual inquiry, of artistic ambition, of range and depth, that inspired not just her readers, but, over decades, her colleagues and peers. I experienced the privilege of her fond gaze and her warm, rigorous offers of ideas – more than I deserved. For the rest of my life, I will carry the moment of her embrace, on her doorstep, and her beginning to talk immediately about the novel of mine she’d just finished.

She mildly observed to me once that she found it troubling that all that knowledge you accumulate – all that craft, all that information, all that experience – disappears immediately when you die. In her marvellous novels, her short stories, but also in the memories that a thousand people hold of some marvellous conversations, some spoken words of unending, resonant truth, A.S. Byatt lives on.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in