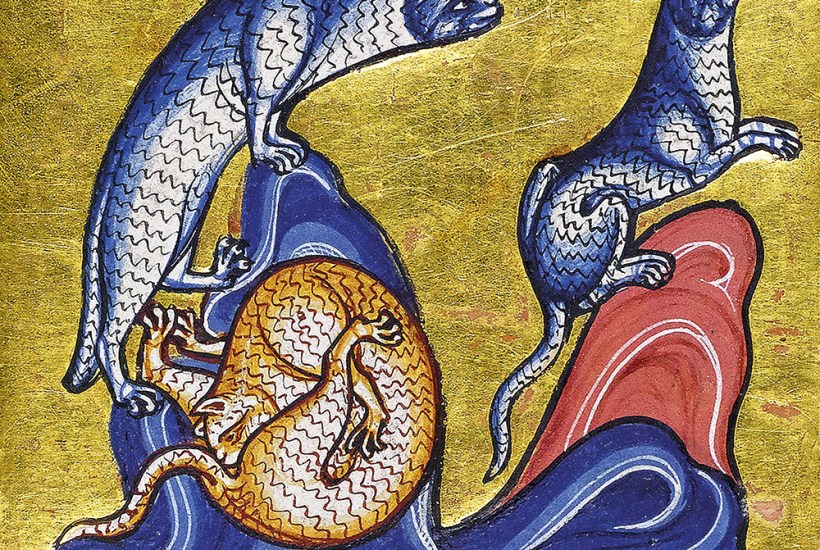

How to hunt an elephant. Find a tree and saw most of the way through it without felling it. Sooner or later an unwary elephant is bound to lean up against it. Down comes the tree and down comes the elephant, which, since it has no joints in its legs, will be unable to get up again. Dispatch your elephant with, um, dispatch, lest the herd arrives in answer to its plangent call. In that case, the youngest of them, being lower to the ground, will be able to lift their fallen comrade back on its feet.

In her second foray into the Old English lexicon and mindset (The Wordhord: Daily Life in Old English came out two years ago), Hana Videen sets out to explore a world where animals hold sway. (A ‘deor’ is the Old English word for any animal and, opening this volume, you are as likely to be confronted by a spider, a dragon, a dog-headed man or a tusked woman as by anything so commonplace as a ‘deer’.) These living, breathing sources of knowledge, enchantment and instruction provided the feedstock for countless bestiaries, which flooded the medieval book market for a good 300 years. No earlier Old English bestiary survives. Still, there’s lore enough in ‘tales, poems and medical texts, riddles and travel logs, sermons and saints’ lives’ to justify Videen’s putting a synthetic one together from the available material.

Though it helps to know a bit of German, Old English is a captivating tongue. What’s not to love about a language that collides nouns in kennings like gange-wæfre (walker-weaver) and wæfer-gange (weaver-walker) to name a spider? (At least we’ve retained the gærs-hoppa (grasshopper). Where it becomes arduous is in its religious texts, which cannot leave anything alone but must constantly be making things act as metaphors for other things. That stiff-legged elephant we started with is God’s law, you see, that ultimately fails to keep us from committing sin. The other adult elephants (Old Testament prophets) try to aid their brother, but it’s only with the help of the little elephant (Christ) that the fallen can rise again.

There is, Videen explains, nothing particularly dogmatic or esoteric happening here; only people’s ongoing effort to explain their world in the most vivid and entertaining terms available. (We do the same today, and quite as unthinkingly: our plugged-in views over smooth-running power brunches about start-up meltdowns would surely addle the most visionary medieval mind: do these people imagine they are machines?) Old English literature becomes much less arduous when we realise that its rhetorical fancies are fancies: they’re a poetic register, not a secret sign, and they aren’t designed to stand much scrutiny. In the Life of St Margaret, for example, poor Margaret is swallowed by a dragon, splits it in two by making the sign of the cross, and steps out into the world again unharmed – making her the patron saint of women in childbirth. If you overthink this, you’ll tie yourself up in knots wondering at a metaphor that kills the mother-to-be while making her the instrument of the devil. The point is: stop being so needlessly scholastic. Focus on the first things the image brings to mind: the blood and the pain and the miracle of birth. Treat the language like a language, not a codex from the beyond.

Much time has passed, of course, since ‘doves congregated in multi-coloured flocks’. Videen is an excellent guide to lost lore (black doves were associated with obscure sermons, and ‘blac’ anyway meant glossy) and sees us safely through some disconcerting shifts in meaning. Today we associate owls with wisdom, ‘yet medieval bestiaries compare the owl’s daytime blindness to the spiritual “blindness” of the Jews, who refuse to accept the “light” of Christianity’, Videen explains. When other, smaller birds flock around an owl in an Old English sermon, don’t assume they’re paying homage to the wise old bird.

Not every Old English text feels the need to find moral instruction in the birds and the beasts. There is also a sizeable quantity of what Videen charmingly terms ‘Alexander fan-fic’ – imaginary first-person accounts of Alexander the Great’s adventures in Ind or Ethiopia or Lentibelsinea (home of the self-immolating chicken, the fabled ‘henn’), or wherever the heck else he was supposed to have got to (sometimes on the back of a griffin). ‘Did people struggle to imagine creatures of Alexander’s campaigns like the teeth tyrant and moonhead?’ Videen wonders. ‘Were the solutions to riddles more obvious then than they are today?’

Though her endlessly fascinating book is chock-full of archival detective stories (and not a few shaggy dog stories too), Videen would rather we entertained the possibility that the early English mind was quite as imaginative as the modern one, just as intelligent, and had not yet lost the art of appreciating a tall tale or even, heavens defend us, a joke.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in