Centralised control results in a hierarchy of out-of-touch elites, neglects local agency, and creates unnecessary layers of red tape and bureaucracy. It stifles innovation, hinders customisation, and leads to inefficiency. This is in part why the Voice to Parliament was rejected, and why the National Curriculum should also be abandoned.

The Australian Curriculum, Assessment, and Reporting Authority (ACARA) serves as the authoritative source, responsible for setting curriculum standards, educational expectations, advice, delivery, assessment, and reporting on the National Curriculum. Established in 2008, ACARA is governed by a 13-member Board with appointments approved by the Federal Minister for Education. Its bureaucracy employs 105 staff, with the CEO earning $438,000 a year and the Chair remunerated at $78,000, resulting in a total annual cost to taxpayers of $29 million.

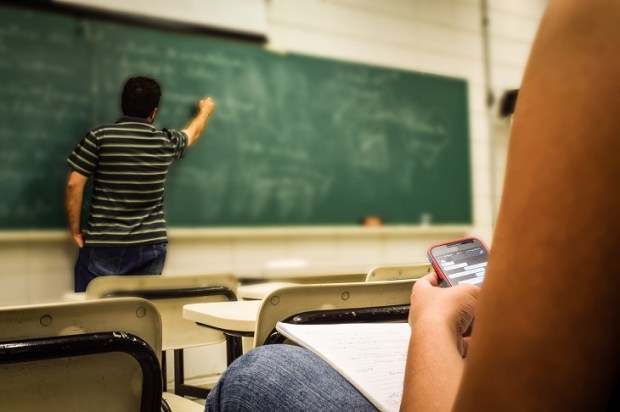

Note that ACARA does not operate any schools or employ any teachers – it is purely bureaucratic – functioning as a layer of office workers dictating directives to those in the classroom trenches.

One of the primary drawbacks of ACARA’s centralised nature is the lack of local agency. When policies and standards are determined at the national level, they often fail to account for the unique needs and circumstances of individual communities, regions, and states. This one-size-fits-all approach ignores the fact that what works in one part of the country may not work in another.

The statistics reveal that when ACARA was established in 2008, the benchmarked Year Nine student reading results indicated that 92.9 per cent of all students were ‘at or above the [then] minimum standard’. However, only 70.7 per cent of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students met that benchmark. In 2022, the figure for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders had dropped to 67.2 per cent. Further, the 2022 results highlight another significant gap, with 91.5 per cent of students in major cities ‘at or above standard’, while only 76 per cent of remote students and 47.5 per cent of very remote students met the minimum benchmark set at the time (benchmarks have since changed). The discrepancy between results in urban and remote areas is stark.

This ‘demotion of agency’ is evident in both the Voice to Parliament and the National Curriculum. Each of these fails, or refuses, to acknowledge the unique challenges and opportunities that different communities face. Most notably, they ignore the vast differences between life in regional and remote areas of the country and life in our major cities.

Neither the Voice to Parliament nor the National Curriculum acknowledge these differences between communities, allowing a centralised bureaucratic elite to mandate policies that may appear sound on paper but are often impractical, unwarranted, or ineffective in practice. Local communities are usually better placed to identify and understand their specific challenges and opportunities, something a centralised and cosseted bureaucracy fails to appreciate.

This lack of local agency results in frustration and disengagement, as communities are forced to follow bureaucratic mandates that don’t align with their particular priorities.

Even within the major cities, the National Curriculum neglects to acknowledge the agency of the local environment. It promotes a one-size-fits-all approach that doesn’t address the varying needs or opportunities of local communities, ignoring the diversity of backgrounds, the culture, the environment, and the perspectives that exist within each one of them.

With decisions flowing from the national level, they must pass through multiple layers of approval and implementation, resulting in a slow and convoluted process. This leads to inefficiency, a lack of accountability, delays in responding to emerging challenges, and limited adaptability. This burdensome administration and reporting process does nothing to address the downward spiral of our children’s academic performance.

ACARA’s 2022 internal survey of staff perceptions of organisational performance revealed that 82 per cent of respondents were satisfied with ACARA’s progress. As part of this, ACARA stated that its Reconciliation Action Plan (RAP) provides employees with the opportunity to support actions aimed at driving ACARA’s contribution to reconciliation and includes various tangible and practical actions to develop and strengthen relationships with First Nations Peoples.

Soon after ACARA trumpeted the high satisfaction level of its staff, the 2023 NAPLAN results, which ACARA implements, revealed that a third of all Australian students, and 52.5 per cent of very remote students, had failed to meet the year nine minimum reading benchmarks.

ACARA has created an ideologically driven curriculum that ignores the true purpose, and the often very particular nature, of education – to the detriment of our students.

This rarefied bureaucracy is out of touch and risk-averse, choosing instead to create and then tick boxes – boxes more often than not with a political rather than educational purpose.

Colleen Harkin is the National Manager of the Institute of Public Affairs’ Class Action research program

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in