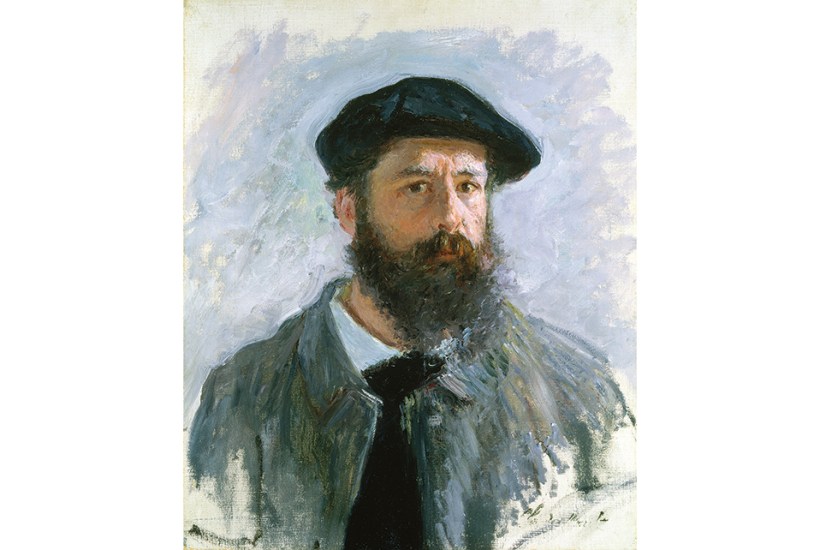

There have been some really good biographies of artists over recent years and what distinguishes the best of them is their sense of context and a lucid prose free from the jargon of the art historian. In the end, of course, any work of art has to be able to stand by itself, but for Jackie Wullschläger her appreciation of Monet’s paintings has been immeasurably deepened by her sense of the man behind them.

‘My approach,’ she writes, ‘stems from the belief that painters transform the raw material of experience into art’, and that material, both the familiar external events and, more illuminatingly, the inner man, is what she gives us here.

Oscar Claude Monet was born in Paris in 1840, the son of a marine merchant. His father’s business interests soon took the family to Le Havre and it was there that the young Monet – known by his first name, Oscar – grew up in a comfortable bourgeois environment. In 1857, however, everything went wrong. His mother died and his father’s business failed. It would be many years before Monet knew financial security again. Even when acknowledged as an artist of some repute, he would still be imploring relations, friends, dealers and supporters for money to cover outstanding accounts, rent arrears and even food. The time when he was able to earn more than 270,000 francs in a single year was a long way off.

The trajectory of his career began with caricatures. As a boy he drew humorous sketches of local figures in Le Havre, shown in a stationer’s shop window. They caught the eye of the artist Eugène Boudin who encouraged the 17-year-old to accompany him on open-air painting expeditions, which in turn led to art school in Paris. Military service in Algeria briefly intervened, but by his mid-twenties the fledgling Oscar Monet had turned into the artist Claude Monet, and was on the road to becoming a professional. His friends included the impoverished Pissarro and Renoir and the affluent Bazille and Sisley, and his passion for painting nature en plein air had taken root.

This compulsion to paint would last his whole life, accompanied by a questing need to innovate, to find ever new ways in which to express both what he saw and what he felt about what he saw. He wrote:

I intend to fight, scrape off, begin again, because one can produce something from what one sees and what one understands, and it seems to me when I see nature that I can do everything, write it all down, and then, when you’re working, nature drives you – it says: go!

At the heart of this book, inevitably, is Monet’s role as the leader and prime mover of Impressionism, the creator of a new language of paint, and it is a story Wullschläger tells with aplomb. She writes of Monet’s and Renoir’s ‘Grenouillère’ paintings of 1869:

In the experimental fusion of light, reflections and movement on the Seine, in the watery world at once vividly rendered and abstracted, in the decomposition of the image through abrupt, accented brushstrokes, beginning to be independent of representation, they contained the elements determining the rest of Monet’s art.

Risible to the critics and public alike, Impressionism began its long, slow journey from derision to epoch-making acclaim with Monet at the forefront. ‘To paint landscape in 1889,’ Walter Sickert could legitimately write, ‘without knowing Monet by heart would be… to betray a want of education.’ Figures, seascapes, cliffs, river views, haystacks, Rouen cathedral, London, the garden, waterlilies, serial painting – they all made for a career that blazed a new way of recording the world which would be pivotal for the future direction of painting.

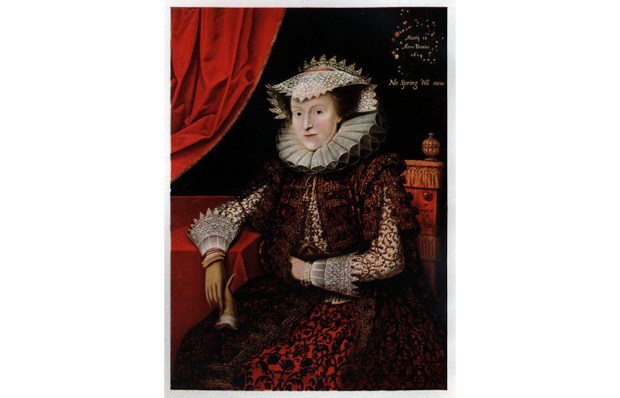

Behind this brilliant, driven man was an important family life, explored here in all its variety. His first wife and constant model, Camille, was a crucial partner in his early development as an artist. Her death in 1879 left him devastated, a naturally uxorious widower with two small children, living, to complicate things, in the same house as the wife and six children of his great patron and friend Ernest Hoschedé. Kind, loving Alice Hoschedé, who eventually became the second Mme Monet, raised Monet’s children, tolerated his absences, entertained his friends and underpinned the successes of his later career. At Giverny, she, and after her death her daughter Blanche, made life possible.

Monet has been the subject of many biographies, starting with a major interview in 1900, but few have engaged so thoroughly with the journals, memoirs and rich cache of his letters. Wullschläger uses these to animate a life of plunging lows and soaring highs, of poverty and wealth, failure and success, despair and happiness. She is equally at home with the historical and cultural context of Monet’s world, with his last close friend Georges Clemenceau, and with the seismic events – the Dreyfus affair, the disastrous conflict with Prussia, the Paris Commune and the Great War – that are the backdrop to his life.

This, though, is not simply good history or good biography. Wullschläger never loses sight of the fact that it is the paintings that matter, and it is her deep engagement with Monet’s art that makes this book such a pleasure to read:

Monet had painted descriptive snowscapes for several years but ‘The Magpie’ was an advance. It reproduces the experience of the cold, stillness, muted sounds of being solitary in snow, watching the play of shadows acquire colour in the changing light. The snowy landscape in the afternoon sun becomes a harmony of whites, silver, pinks, yellows, cobalt blues, cast with long lavender, lilac and indigo shadows, contrasted with a warmer reddish sky behind the trees.

Has anyone written better of that perennially gorgeous Christmas card?

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in