The former governor of the Bank of England, Mark Carney, recently compared the British economy with that of Argentina. This was typical of those Remainers who cannot imagine that a country ignoring them could possibly succeed, and who often seem to will it to fail. That Carney’s sneer did not merely provoke laughter is because far from being a random remark, it stems from generations of negativity about Britain. This hangs albatross-like round our collective neck. So deeply has it penetrated our culture that I suggest it accounts for much of the failure to profit from the Leave vote.

Over and over again, British policy has been marked by apology, concession, timidity and lack of ambition. Now it appears that whether under a Conservative or a Labour government we are drifting back humbly towards the EU, hoping that they will in return forgive us for the 2016 rebellion. So we seriously contemplate the old French plan to make us an EU satellite, politically, militarily, economically and intellectually – just as the EU, serenely unnoticed by its British devotees, lurches from crisis to crisis.

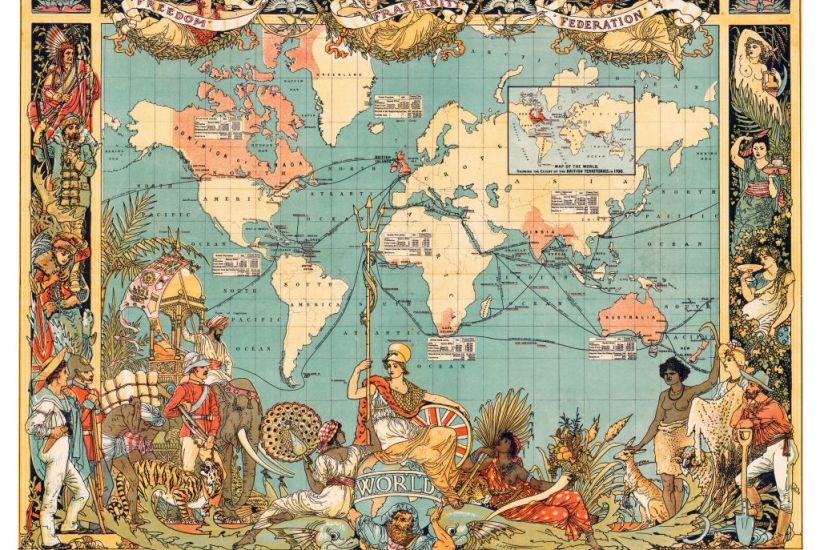

The Remainer/Rejoiner mindset, inside and outside the Conservative party, is founded on ‘declinism’ and a perverse obsession with the loss of empire

Would we do this if our political establishment had not long convinced itself that we are a nation that has seen better days – a faded beauty, as Harold Wilson put it – and should not try too hard to assert its own interests? We as a nation know so little history that we are easily taken in by myths and exaggerations. The most damaging of these is the belief that once we were a ‘superpower’, but now, through political, moral and economic failures, we have become merely an insignificant offshore island.

This idea goes back a long way. Perhaps to our defeat in the Hundred Years’ War, which sparked the Wars of the Roses. Certainly it emerged again after the independence of the American colonies, when the First Lord of the Admiralty declared that ‘we shall never again figure as a leading power in Europe.’ Our more recent national pessimism dates from the 1870s, when cheap German manufactures began to invade British markets, and there began a chorus of economic lamentation that has persisted until today: we are always on the verge of economic disaster, despite somehow remaining one of the world’s richest nations.

Even worse was the fear of the Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain that Britain was a ‘weary Titan’, too small to bear its global burdens. ‘Lo, all our pomp of yesterday / Is one with Nineveh and Tyre,’ wrote Kipling, throwing a wet blanket over Queen Victoria’s diamond jubilee.

After both the world wars, despite being victorious, the sense of vulnerability and decline soon returned. The motives for entering the European Community in 1973 included fear of becoming (in the words of the Foreign Office official who conducted the negotiations) merely ‘a greater Sweden’. Remainers assured us that outside the embrace of Brussels we would be a larger Albania, ridiculed by all. Leaving the EU seemed to them the delusion of idiots nostalgic for an impossible return to Empire – proof of how much the notion of national power has become linked to a memory of empire.

Yet this vision of our past, present and future is based on a gross misunderstanding of the past. There was never a golden age in which Britain was a superpower. As its rulers knew, it was a small country with a relatively small population. It spent money on the navy when it had to – though in the heyday of Victorian power the Royal Navy had only some 30,000 men, exactly the same as today. Consequently, the army was tiny: Bismarck joked that if it ever invaded Germany he would send the police to arrest it.

Statesmen constantly fretted about security. The French were always a bugbear, even to men as tough as Wellington and Palmerston, who built huge forts on the south coast. The War Office repeatedly vetoed a Channel tunnel for fear of a surprise French invasion. Coastal defences still stand in Australia and New Zealand, built to fend off attack by France, or America, or Russia. Then came fear of the Germans – a fear reflected in best-selling novels as well as in official reports.

All this was a world away from the confidence of a ‘superpower’. When Britain reluctantly went to war in 1914, it was largely through fear of being isolated and surrounded by enemies, whichever side won.

Victory led almost at once to appeasement of Germany and what now seems an absurd suspicion of France, Europe’s greatest military power, whose air force, it was feared, might bomb London. Terror of war reached extraordinary levels during the 1930s, with Italy and Japan adding to the threats. One 1934 novel had the whole population of Britain being killed by poison gas, except for a family visiting the Cheddar caves.

In 1939, when Britain at last decided it must stand up to Germany, it was militarily dependent, as in 1914, on the French, whose army was ten times the size of the British Expeditionary Force. Commented the French general staff, ‘it is for us to give them moral support, to organize the strategy of the campaign, and to provide the necessary planning and inspiration.’ When French inspiration failed, the British army – smaller than the Belgian or the Dutch – had to flee. Eventually, Britain mobilised huge forces: 90 per cent of men became part of the war effort, and 55 per cent of national expenditure. Evidently, this could only be done for a short time, and it would be absurd to consider British military power in 1945 as the norm from which we have declined.

Of course, Britain had the support of its vast empire. Empire, and the ‘loss’ of empire, have long been central to the perception of decline. Yet as the dangerous period from 1940 to 1942 showed, empire was a source of vulnerability too. Imperial Britain was fighting three major powers in a global war—more than any other state in history has ever attempted. To defend Asia and Australasia from Japan, it could only spare two capital ships, which were rapidly sunk off Malaya.

This disaster is often taken as the death-knell of the Empire, with some reason. But only because the empire always relied on being left alone by major predators and accepted by its subject peoples. It was never a powerful military force, and the troops it had were scattered in penny packets. The Afghans, the Zulus, the Boers and the Sudanese inflicted embarrassing defeats during the Empire’s high noon. The Royal Navy could not defend against major land powers, so a Russian invasion of India was a recurring fear: ‘compared to our empire’, lamented the first Lord of the Admiralty in 1901, Russia was ‘invulnerable’, with ‘no part of her territory where we can hit her.’ Britain, he concluded, could not be both a major naval and a major military power – the essence of being a superpower – and this at the time when British power was at its zenith.

But Britain’s imperial power was always largely a matter of show: as a disillusioned George Orwell put it, being a ‘hollow posing dummy… trying to impress the “natives”.’ The empire was based on trade and broad acquiescence. Yet it brought little economic benefit to Britain during most of its existence (though it enriched some of the colonies) and arguably it distorted economic development. Britain did not need an empire in order to trade: the United States has always been the bedrock of its global trade and investment, and Argentina was a major supplier of food.

There was no possibility, and little appetite, to make the Empire a permanent global federation. Expensive and potentially dangerous global strategies were required to defend it. There was no way Britain could maintain it by force, nor did most of its people and politicians wish to do so. When India became independent and broke up, its central provinces (bigger than England) had only 17 British officials, 19 British police officers, and no British troops. Only from a very peculiar viewpoint can the end of empire be seen as decline.

In short, Britain today is not a decayed superpower: it never was one. Empire was a burden at least as much as a benefit – ‘millstones round our necks’, said Disraeli. Britain today is what it has been for several centuries: one of the world’s half-dozen or so most powerful states. The great change in the world – predicted at least as early as Napoleon – has been the rise of America, the only global superpower in history. If America’s rise equates to Britain’s decline, then every other state has declined too, including China and India, in the 18th century the world’s biggest economies. Britain’s relative power, compared with our traditional peers – France, Germany, Russia, Italy, Spain – has actually increased.

So let us and our rulers try to assess our power, interests and role in the world realistically, not based on fantasies about an ill-understood past. The Conservative party – which Disraeli called ‘the national party… the really democratic party of England’ – as it seeks to find a raison d’etre before it is too late, might well start here. Whether they like it or not, they are indelibly associated with Brexit. The Remainer/Rejoiner mindset, inside and outside the Conservative party, is founded on ‘declinism’ and a perverse obsession with the loss of empire. The Brexit vote, on the contrary, spurned declinism. Unless we have governments—especially Conservative governments – that can do the same, Brexit will inevitably fail.

National pessimism may then prove self-justifying. And the Conservative party will struggle to have a future.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in