Robyn Davidson never set out to become a writer. ‘It did not form my identity,’ she tells us early on in her memoir Unfinished Woman. ‘In my own mind I had simply pulled another rabbit out of a hat. As I had done all my life with everything.’ The rabbit, in this case, is the ability to capture an exciting and complex life with insight and humour.

Born in 1950 on a cattle station in Queensland, Australia, Davidson was the second daughter of a handsome war hero from a privileged background. Home was a place full of ‘dust and wide verandas, comfortable old chairs and good horses, though never adequate cash’. Her mother, Gwen, a lover of the arts, was ‘ground down by country life and yearned to return to the city and all that it represented… Loneliness engulfed her’, Davidson tells us. ‘There was so little relief from it except music and I suppose, to some extent, her children.’ The family moved from the cattle station to an ‘outer, outer suburb of Brisbane, to be “closer to doctors”’. It was in this house that Gwen tragically unravelled: ‘My mother hanged herself from the rafters of our garage, using the cord of our electric kettle.’ Davidson was 11 when this seismic rupture occurred.

While still a teenager, she left Brisbane for Sydney, where she slept rough until she found an abandoned cottage to squat in. She foraged for food, eking out an existence on a bare bed frame, reading books by candlelight. Then there was a job as a poker dealer in an underground gambling den. The gangster owner of the club, a married man in his forties, became her lover. When she decided to leave the underworld, she was sexually assaulted at knifepoint. A stint at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music ensued (she is a gifted pianist), and more squatting, odd jobs, drugs and boys. It was the 1960s after all.

Aged 26, Davidson headed off on a solo 2,700-km trek across the Australian desert with a dog and four camels. She had no intention of writing about this journey, but a piece commissioned by the Sunday Times and another by National Geographic brought attention from the literary world. In the 1970s, she moved to London to write Tracks for Jonathan Cape. She found a room in Doris Lessing’s rambling Kilburn home – the older writer becoming something of a mother figure – where she also made friends with Bruce Chatwin.

Published in 1980, Tracks was an enormous success. Hollywood came knocking, but she ‘foolishly’ turned down Sydney Pollack’s offer of ‘a very large sum of money’ for the rights. (The Australian director John Curran eventually directed a film in 2013.) The book brought her fame, and Davidson ‘feared the loss of anonymity and privacy, and with it a particular kind of freedom: to observe rather than be observed’. The pull towards freedom and the stability needed to capture it on the page is a tension threaded throughout her life.

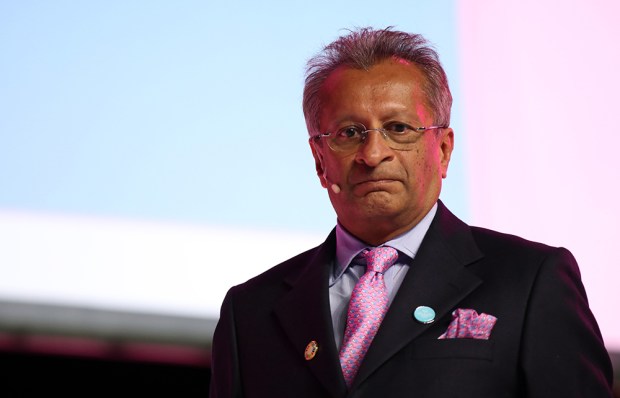

Her second book, Desert Places, followed a nomadic tribe in India. Thus began her love affair with the country. Around this time, she came to know the charismatic Indian aristocrat and politician Narendra Bhati, whom she first met on the tarmac of Jodhpur airport. Years later, he showed up at a dinner party in London. ‘It was inevitable that we should eventually become lovers,’ Davidson writes in her trademark deadpan way. ‘He said he had fallen in love with me all those years ago.’

Narendra helped her find the Rabari tribespeople, with whom she would travel as ‘part of an exodus of a million sheep and their herders… to find grazing’. Davidson has an affinity with nomads. In Unfinished Woman, she laments how

the traditional relationship between herders and farmers, a reciprocity beneficial to both, was being broken down by industrial farming practices, by government programmes penalising mobility and by the sheer pressure of population on forests and grasslands.

Unlike her first desert trek, this one was ‘the most gruelling and distressing thing’ she had ever done. She fell very ill, as did the family she travelled with, but her ‘belief in the value of nomadic lifeways’ never wavered.

During these years, she spent time with Narendra at his remote residence in the Himalayas:

There were no roads to the house. You had to climb through 4,000 feet of oak jungle and terraced fields to reach it… Ostensibly I went to the mountain house to write, but really I went there to reconnect to the wildness and silence of a deeper, older world.

Narendra’s physical safety became a concern after an attack on his life, and his drinking increased. Then he mysteriously disappears from the narrative – which is not told chronologically but dips in and out of time frames and places, perhaps reflecting the author’s peripatetic life spent travelling between London, Australia and India.

When Davidson turned 46 – the age her mother was when she died – she tried to write about her; but it became ‘a series of detours, shuntings, sidings, hold-ups, dead ends’. She thought she ‘should be able to make out some sort of trajectory… a narrative’. The book about her mother ends up being Unfinished Woman:

We take our mothers into us; that is where they live. In order to write about her and her time, to honour that nanoscopic existence, I had to write about myself and my own time… Not a narrative, nor a reconstruction, but rather a searching through the mysterious residue left by time and events.

Davidson’s life has been full of adventures, encounters, love affairs and losses. Yet rather than simply describing these, she pulls them apart, examines them and lays them before us so as to question what sort of life we are living, who lives inside usand what do we plan to do with the ‘mysterious residue left by time and events’.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in