Uzeste contains 387 people and a dead pope. The tiny French village is one of the less glamorous papal resting places, where the earthly remnants of the unfortunate Clement V await the General Resurrection. How much of Clement is left is hard to tell. As his body lay in state after he died in 1314, the church was struck by lightning, causing a fire that consumed his corpse. The medieval mind assumed that this was an earthly metaphor for the eternal flames that consumed Clement in Hell.

Many identify this unfortunate pontiff as the first victim of the Curse of de Molay. Clement, a particularly craven occupant of the see of Peter, had moved the papacy to Avignon on the orders of the French king Philip IV, who then proceeded to co-opt him into his campaign against the Templar Order.

The Knights Templar were initially a military organisation formed with the aim of protecting pilgrims to the Holy Land. Soon, however, they had grown into a pan-European behemoth. This change of status brought enemies. King Philip in particular hated the Templars, desiring, it is said, their power and their money for himself. After the death of their protector, the previous pope, he moved quickly, with Clement’s connivance. A date was set for mass arrests across France, with Templars from Grand Master Jacques de Molay downwards seized and charged with trumped-up claims of corruption, heresy and sodomy. Many of them – de Molay included – would later be burnt at the stake. The date set for the arrests was Friday 13 October 1307.

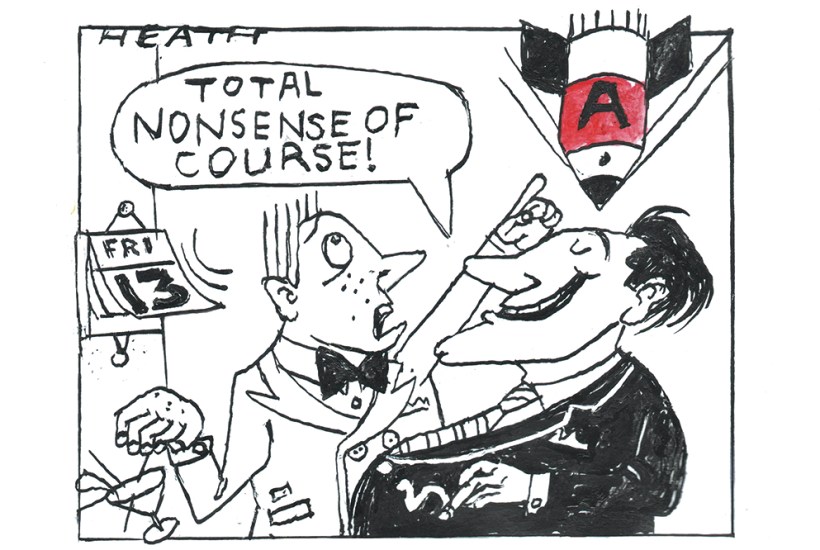

The rapid subsequent deaths of Clement, then Philip and then, within, appropriately, 13 years, the whole of his dynasty, set those fertile medieval minds whirring again. Had the order cursed the date of their arrest forever? Fridays were considered a day with particular power, being the day of the Crucifixion. Thirteen already suffered the concomitant association with Judas, the 13th person to take his seat at the Last Supper. Even before Philip’s plot, Friday 13th seemed destined to be a day associated with bad luck. So it became, apart from in Italy, where Friday 17th is unlucky instead, due to its Roman numerals – XVII – being an anagram of vixi, Latin for ‘I have lived’.

Italians aside, the superstition persists, even among those not suffering from the medicalised fear of Friday 13th: paraskevidekatriaphobia. An infamous British Medical Journal study in the 1990s found that the chances of being involved in a traffic accident on the M25 on a Friday 13th compared with the rest of the year ‘could be increased by as much as 52 per cent’. In the subsequent newspaper panic, the researchers insisted that their findings were ‘tongue in cheek’ and that people shouldn’t change their plans on Friday 13th. Unless, of course, what you have planned is the mass arrest of the Knights Templar.

It is strange that a date can link those frazzled remains found in Uzeste to the traffic patterns of the M25 in the late 20th century. But that’s the rather wonderful thing about superstition: it doesn’t make sense at all.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in