While looking at Claudette Johnson’s splendid exhibition Presence at the Courtauld Gallery, I kept trying to pin down an elusive connection. Her works are large drawings (sometimes very large – one reclining figure is more than two-and-a-half metres wide), and each one zooms in on a single figure seen in close-up, often larger than life-size. They reminded me of something, but for a while I couldn’t place it. About halfway round I got it. They look a little like fragments from the cartoons Renaissance masters made as templates for painting. These, too, tend to concentrate on the human body on a monumental scale.

Claudette Johnson is female and she is black, neither of which are as unusual in the art world as they were when she began her career in the early 1980s (one respect in which the world has become better since then). But she is a highly unusual artist for another reason. Those who dedicate themselves to drawing and work from live models are scarce nowadays, and Johnson does both.

There are quite a few artists around who depict what David Hockney likes to call the ‘visible world’ (sometimes described as ‘figurative’), but these days they are more likely to work either from photographs or imagination. When we met, Johnson told me why, despite the difficulties, she prefers to sit and draw in front of a living, breathing person. In fact, she does this partly because of the difficulties. Working from life, she explained, is not only more challenging but also more embarrassing (which was one of the reasons why Francis Bacon used photographs rather than living sitters). ‘When I’ve worked with someone I didn’t know particularly well,’ she said, ‘there’s always an initial period of awkwardness.’ That’s not hard to understand. After all, artist and model are in close physical proximity and in her case, as she works slowly, the process goes on for weeks on end. To add to the embarrassment, one of the two people in the room is scrutinising the other’s appearance very closely.

Sometimes, Johnson begins with ‘sketches or lighter-weight drawings’ to get over ‘the nervousness of looking intently at somebody I don’t know very well’, and also to fend off negative reaction (‘Ooh. Is that what you are seeing?’). Sometimes she confesses to issuing instructions: ‘Do not look at that when I leave the room!’

Then there are the technical complications of working from life. A photographic image never alters but, as many artists have noted, reality does so constantly. Johnson finds that ‘the light changes through the session, therefore I have to shift my description’. Also a photograph is already flat, whereas obviously a human being is not. But Johnson finds that ‘transferring a three-dimensional figure into a two-dimensional space, creating that illusion of depth and volume and solidity, fascinates me’.

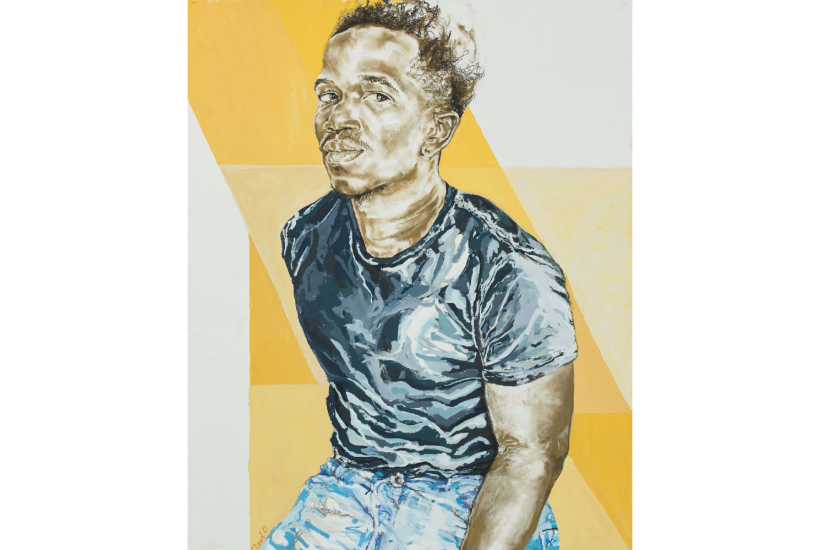

It is a moot point whether her works should be classified as drawings or paintings. Perhaps they are both. Sometimes they include areas of brushwork as loose and free as a Pollock or De Kooning. The whirl of brush strokes that make up the dress worn by the ‘Figure in Blue’ (2018) could be extracted and displayed as an abstract painting. Johnson admits that she ‘loves handling paint’ enjoying its ‘fluidity’. But really, she goes on, she thinks of herself ‘as someone who draws’.

The frontier between these two kindred art forms is not a sharp one, more of a spectrum. But the distinction isn’t solely an academic one. It affects how artists think of themselves and what they do. The late Paula Rego once told me that she was at heart a ‘drawer’ (for obvious reasons the traditional term ‘draughtsman’ isn’t a good fit either for Rego or for Johnson).

Rego found her ideal medium in pastel, as did Edgar Degas, another archetypical painter/draughtsperson. This is, of course, a medium in which you can draw in colour. Johnson frequently uses pastel for the faces and flesh of her subjects and gouache or watercolour for their clothes or (alternatively) the settings in which they appear. The woman in ‘Untitled (Yellow Blocks)’, 2019, for instance, is standing in front of a series of rectangles of yellow, some paler some darker, but the figure herself is entirely monochrome and executed in pastel.

Some painters aren’t all that good at drawing. Bacon’s friend Lucian Freud used to say that ‘Francis couldn’t draw at all, but he was so brilliant he made you forget it’, which was a good way of putting it. With Rego, Degas and Johnson too, as one can see from all the works in this exhibition, drawing comes first.

She is another specific variety of artist in that her interest is almost entirely in the human face and body, which, she points out, is among the most intricate objects we ever set eyes on – and certainly the one that we, as fellow humans, know most intimately. ‘People forget that the geometry of the body is more complicated than any building or man-made structure you can think of. The way things sit together. You cannot lie and be convincing about the body. Everybody knows if a line is wrong or if the foreshortening isn’t quite there.’

Perhaps the most distinctive aspect of Johnson’s art is that for many years her subjects were exclusively black women (in the past decade she has added black men to her repertoire). There were reasons for that choice. At art school she was the only black student in her year, and she wanted to make herself more visible. ‘But more widely I felt that black women were invisible, especially in art.’ In western painting of the past, ‘we’re on the periphery, we’re offering the flowers, we’re holding the fruit. We’re there to put into relief the white woman who’s at the centre – Manet’s “Olympia” being the obvious example – or we’re just absent.’

Drawing from life is a marvellous way truly to see other people because to do so you have to look at them really, really hard. In doing so for more than 40 years, Johnson has made images of a group of people who – it is perfectly true – were largely overlooked in western art. And in doing so she has made pictures that are at once monumental and intimate, fresh and contemporary while fitting into a long tradition.

Her achievement is clear from the exhibition at the Courtauld, which includes works spread over four decades. She began strongly and seems, if anything, to be getting stronger as she goes on. Working from life seems continually to refresh artists who work in that way.

When I asked Johnson whether everyone should go to life-drawing classes, she at once answered: ‘Yes!’ The reason is that through drawing you learn so much about human beings. ‘Everything is normal, everyone is interesting, everything is exciting to explore!’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in