‘Do women have to be naked to get into the Met Museum?’ More than 30 years after the Guerrilla Girls posed this question on their feminist poster, the answer suggested by the Royal Academy’s Marina Abramovic retrospective – touted as the first solo show by a woman artist in the main galleries – is: ‘They don’t have to, but it helps.’

Abramovic achieved fame in the 1970s with a series of gruelling performances that tested the limits of her mental and physical endurance. But without the nudity, performances such as ‘Freeing the Body’ (1975), in which she danced till she dropped, and ‘Lips of Thomas’ (1975), in which she consumed a kilo of honey and a litre of wine before flogging herself, incising a communist star on her stomach and lying on a cross made of ice, would not have attracted the same degree of attention.

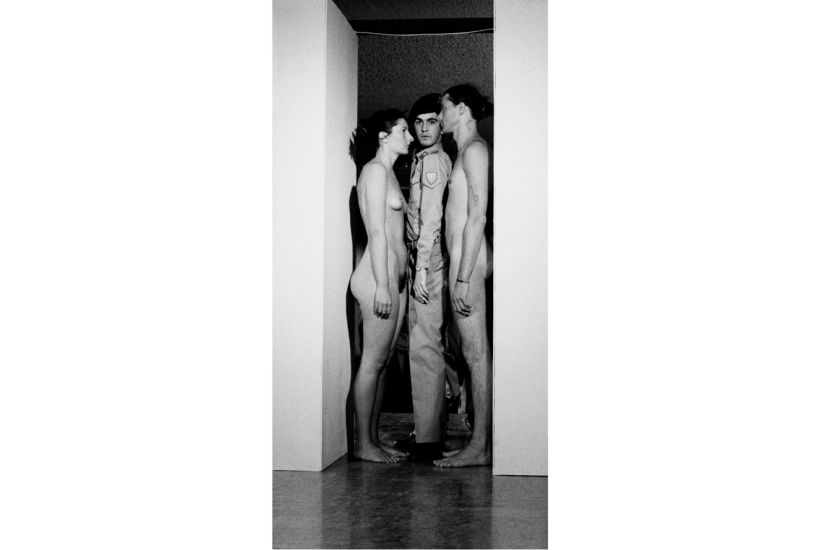

It’s no accident that a performance involving nudity is the talking point of this show. Now 76, Abramovic no longer performs in person but has trained up a roster of young artists in her method to revive four signature works. Two of them are presented by nude women; a third, ‘Imponderabilia’ (1977), recreates a legendary performance in Bologna in which Abramovic and her then partner Ulay stood like human caryatids in a gallery entrance obliging visitors to squeeze between their nude bodies until the polizia arrived to spoil the fun. The boys in blue won’t be descending on Burlington House as the door in question is well within the gallery precinct, and embarrassed visitors are given the option of slipping round the side.

The whole exhibition is sanitised. The pile of rotting cow bones Abramovic scrubbed clean in ‘Balkan Baroque’ (1997), stinking out the basement of the Italian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, lies clean and dry on the gallery floor. Her more violent performances are documented in photographs, while videos of less shocking ones play on screens: ‘Freeing the Voice’ (1976), in which she screams herself mute, fills adjoining galleries with the sound of souls in torment.

What’s it all about? Purgation. The artist’s suffering, we’re told, is cathartic, helping us overcome our fear of pain and death. No wonder it’s purgatory. But the big problem with this show as an art exhibition is that it contains almost nothing of visual interest. Abramovic’s performances were always closer to spectacle than art. A few repeat performers can’t breathe life into this archive of an exhibition: their contributions have all the thrill of a tribute act, only of interest to diehard fans. Fortunately for the Academy there are plenty of those. It’s rumoured that the artist may appear at some point to engage with her public in the Academy courtyard. Perhaps as a grand finale she could have herself fired across it from a cannon, then this damp squib of a show could go out with a bang.

It’s hard to imagine a better antidote to Abramovic than Sarah Lucas: she was always the least pretentious of the YBAs and her irreverence seems immune to ageing. Her retrospective at Tate Britain, Happy Gas, is a reunion of all her trademark lines: cellulite-dimpled ‘Bunny’ sculptures made of stuffed tights; concrete casts of giant marrows with names like ‘Kevin’ and ‘Florian’; everyday objects clad in appliquéd cigarettes; and bawdy visual puns confirming allegiance to British working-class humour. A ‘Man’s Wanking Armchair’ (2000) with a mechanical arm faces a wall of blown-up spreads from the Sunday Sport with misogynistic headlines like ‘Fat, Forty and Flab-ulous’ (1990). Too skint at the time to afford art materials, she decided an artist didn’t always have to make things: sometimes it was enough to point them out.

It was a shortage of funds that first made her turn to tights as a modelling material; now she can afford to combine them with bronze. The spine of the show is a parade of headless bunnies sprawled across chairs in various stages of abandon. If Abramovic takes inspiration from the baroque, Lucas looks a lot further back: ‘Sugar’ (2020), sprouting multiple breasts formed of stuffed tights with knots for nipples, is a cross between Diana of Ephesus and the Venus of Willendorf. The worry is that more recent works in polished bronze will be taken seriously.

Early photos of the fresh-faced young Lucas with that famous banana are followed in the final room by a series of blurry recent shots of her wreathed in tobacco smoke which she describes as ‘hellish’. Better hell than purgatory. Incidentally, the Academy has a short memory: the first woman to be given a retrospective in the main galleries was Liz Frink in 1985. Frink slipped through the glass ceiling without fanfare. What’s more, she was offered the presidency and refused because it would have interfered with her work. If that’s not sticking it to the patriarchy, I don’t know what is.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in