Is there a collective noun for platitudes, I wonder? An anthology, perhaps? Never mind, I’ve got a better one. A couple of weeks ago, given the performance of our Prime Minister during the Voice referendum campaign, I would have said an ‘albanese’ would fit the bill nicely. But now he’s been trumped. I now propose a ‘pearson’, which has the added attraction of a degree of alliteration. A pearson of platitudes. Has a nice ring to it.

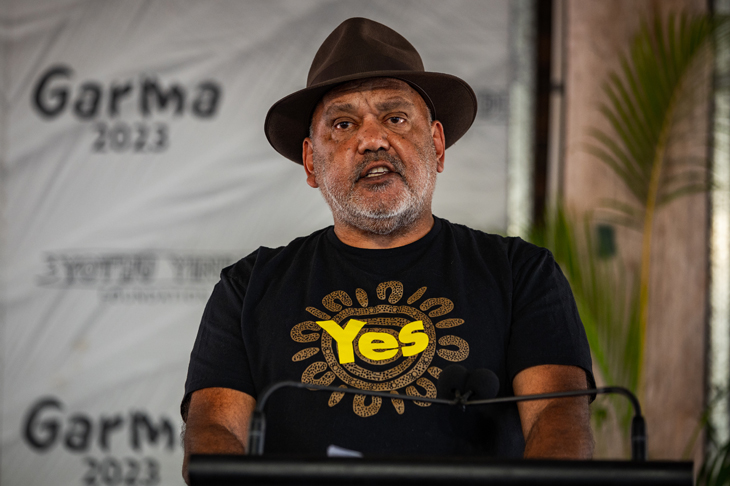

What prompted this thought was listening to Noel Pearson’s recent speech to the National Press Club. For forty or so minutes the platitudes followed each other with the sonority and relentlessness of the main theme in my favourite Australian composition, Ross Edwards’ First Symphony Da Pacem Domine.

But from within this essential dross, a couple of things emerged.

Firstly, at one point, Pearson described the Yes camp as being caught between terror and hope. That immediately struck a discordant note – an implied rebuke to No voters – but it also highlighted how inappropriate this whole campaign has been, beginning with the proposal itself and ending with the way it has been propagated. That one side should consider the possibility of an adverse outcome as one inducing terror, tells you that this is not a thing that we should be contemplating putting in our constitution. Is our constitution really that flawed? It certainly tells you this is not a minor change. Something that would change our constitution to this extent surely should require a comprehensive constitutional convention?

The constitution says nothing about our history, our values or our aspirations. It says nothing about our rights as individuals. It is, in fact, a very prosaic document. It is not like the American Declaration of Independence. It does not hold any truths to be self-evident. It contains no lofty sentiments.

It is not, as is often claimed, the ‘birth certificate’ of our nation. If you are looking for a slick but specious analogy, a better choice would be the ‘pre-nuptial agreement’ of our nation. But, in fact, it is neither of those things.

Firstly, our constitution is a power-sharing agreement between the Commonwealth and the states and, secondly, it is an operating manual for our parliament. Nothing more. It is, in effect, a contract – one which is subject to the jurisdiction of the High Court. As a contract, it is not an appropriate vehicle for emotional or feel-good rhetoric. That would introduce ambiguities that can, and almost certainly will, have unintended consequences.

Who we are as a nation – our values and aspirations – is reflected in the democratic traditions and institutions we inherited from Great Britain. And, more importantly, in our legislation, which has made us one of the most diverse, tolerant and generous nations on Earth. It is in our legislation that we must look to enrich all the people, to alleviate disadvantage, to unite us and to recognise past injustices. All that we require from the constitution in this respect is that it offers no impediments to such legislation.

The constitution does not actually achieve anything. It simply defines what our institutions of governance can and cannot do. In 1901, it allowed the parliament to extend the vote to all Aboriginal people, both men and women. Indeed, it encouraged them to do so by virtue of Section 25. That the parliament declined to do this is not a failure of the constitution. As I said, it is through our legislation that we achieve things. The constitution should not be punished for sins it never committed.

Pearson’s promise is that if the referendum fails, it will not be accepted with equanimity by the Aboriginal people. I have written about this before. https://www.spectator.com.au/2023/09/winning-the-peace/

The second thing that Pearson let slip goes to the nature of the Voice. This Voice is being sold as a means of achieving constitutional recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, in a practical way by giving them a say in legislation that affects them. Most people believe this is intended to redress Aboriginal disadvantage. And that is the way it is being sold – an appeal to the fairness of the Australian people. And many of them would think once the ‘gap’ has been closed, then the Voice would no longer be needed. But they are being deceived.

Pearson told the Press Club that once the gap had been closed, the Voice would still be needed in perpetuity to allow Aboriginal people to offer their unique perspective on any matter. To add value, as it were, to our nation. Such conceit.

Which leads me to my pet peeve of the moment. A major problem for the Yes case is that the Voice is supposed to be advisory only. Albanese, and his acolyte Chris Kenny, repeat this refrain ad nauseam. Recently, Senator Jacinta Price asked why, if the Voice is supposed to be an advisory body only, the words ‘advice’ or ‘advisory’ do not appear in the new provision. I have been raising this issue regularly for over a year in my book The Indigenous Voice to Parliament – the No Case, in my articles, and in letters and comments to newspapers.

The response to Price was that eminent legal minds believed ‘advice’ was ambiguous and could be thought to contain an implied obligation that the advice must be accepted. It was thought that the more opaque phrase ‘make representations’ would remove, or at least lessen, this potential ambiguity. However, it seems to me the proposition that – in order to make it clear that this is an advisory body only – the words ‘advice’ and ‘advisory’ must be avoided, is absurd. Nonetheless, if it is necessary to resolve any possible misunderstanding on the part of High Court judges, would not a specific caveat to the effect ‘Representations emanating from the Voice will not be binding on either the parliament or the executive government’ send a clear signal to Their Honours that this is indeed an advisory body in the strict sense of the word?

It staggers me that I am apparently the only one making this point, given how pivotal it is to the main legal arguments surrounding the Voice. The absence of these simple and unambiguous words tells you the Voice is not intended to be advisory only. I have written about that, too. https://www.spectator.com.au/2023/09/powerless-advice-or-powerful-instruction/

Why no one has asked Albanese to explain this oversight is beyond me.

So here we have a permanent race-based body, sticking its nose into anything and everything – forever – and with, at the very least, considerable ambiguity regarding its constitutional reach or powers.

The fact that Albanese has stated he will not legislate a Voice if the referendum fails, and Pearson’s vision of a permanent third chamber, tells you that this is not about eliminating Aboriginal disadvantage. You are being lied to.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in