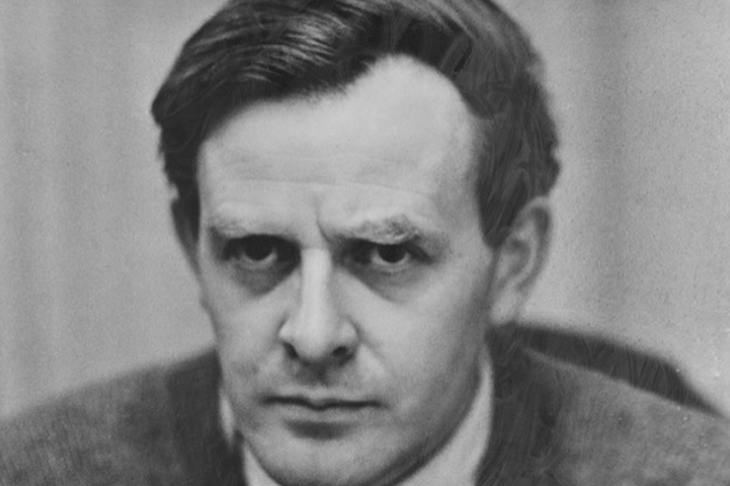

John le Carré was one of the more extraordinary popular writers of the last half-century (and more) and part of what makes him so extraordinary is the way he can confound the distinction between trash and treasure. He was also to an extraordinary degree a magnetic personality with performative skills to rival the starriest actor and these are on show with a mesmerising degree of dexterity and arguably disingenuous candour in the engrossing and bewildering new doco, The Pigeon Tunnel by Errol Morris which has just started screening on Apple+.

It is David Cornwell (as he was born) weaving the wind of his self-scrutiny in order to satiate the curiosity of his interrogator or leave him none the wiser or both. It runs for ninety or so minutes and feels longer as the attempt is made very formidably by Morris to plumb the depths of a personality which betokens a master of a whole theatre of personas which are needful for this public confession from beyond the grave: David Cornwell died in 2020 at the age of 89. And there is a certain irony in the fact that this apparitional performance on le Carré’s part should coincide with the publication of Adam Sisman’s The Secret Life of John le Carré, the mini-life of the master of the great game (as Kipling called spying) which catches up with the various women who had affairs with him and who were by more or less mutual agreement excluded from Sisman’s full biography published in his lifetime though they testify to a compulsion for intimacy, at any cost, that is a bit creepy and not incomptatible with Cornwell’s professed devotion to his wife Anne.

This is not represented in The Pigeon Tunnel doco though le Carré does not deny the shadow of it or indeed anything that might engender a dim view of him. This rhapsody of iron self-portrayal is in fact very close to le Carré’s book about himself that followed rather rapidly in the wake of the impeccably thorough biography.

The Pigeon Tunnel: Stories from my Life (2016) was le Carré’s depiction of the imaginative world he inhabited with all its dreamscapes and hallucinated epiphanies and Errol Morris is brilliant in the way he brings them to life with the immense help of Cornwell’s grave and truth-telling admission of the mind’s capacity to invent its truths with an impassioned need to recollect what has been imagined with an overwhelming intensity the mere facts could never match. So we get recurrent shots of the pigeons being blasted away.

We also get the recapitulation of the stories about le Carré’s father Ronnie Cornwell. There is the unforgettable image recreated here of his father, attired in the striped get-up of a convict, waving to the boy Cornwell from the upstairs window of one of the prisons to which he was confined. Of course it couldn’t have happened which le Carré sombrely admits to his interviewer but the symbolism is indelible and it reflects the central truth that Ronnie Cornwell was a stupendous con man who at some level held the key to his son’s sense of the doubleness of the world. And – almost needless to say – there is a lot of Cornwell saying what is truth when it all gets down to it though he knows all too well that having a father like Ronnie was the great gift providence gave him like a curse.

We don’t quite believe (or do we?) le Carré’s portrait of himself as someone who had to pretend to belong to a class that was not his. We believe him absolutely when he talks of the pain of his mother running off in the middle of the night with no thought (he thinks) of her two sons and we believe absolutely in the monster conman father who cannibalised his son’s every attempt to look after him. Le Carré bribes people in Indonesia, he bribes people in Switzerland, he offers to buy a farm in Dorset and pay his father an allowance to let him live on it. He sketches with a dizzying gravity and reasonableness the undoubted horror of all this. His lack of love, his lack of tears, the terrible demand that was laid on him of ministering to a man who fantasised his way into dream kingdoms. And still there is the voice of the old Viennese hotel clerk: ‘You’re father was a great man.’

And David Cornwell who has sold millions and millions of books makes it clear that what his father did was morally within a stone’s throw of what other people do and are admired for.

He’s very knowing – and never less than confessional – about the duality of being a spy (as he was briefly) during the Cold War. He sees Errol Morris coming and plays up to the piquancy of the moral dialectic. At times he sounds as if he’s milking the moral paradoxes but then the difficulty with le Carré is that he’s always in danger of milking everything because of his consummate histrionic grandeur. You get a few touches of this when he assumes a Russian accent or when he puts in what he says is an Etonian accent as Nicholas Elliot, Kim Philby’s naive friend. He’s good when he talks about Philby as not so much a double agent as a supreme traitor and how could he give him the time of day (or chat with him at a Soviet party) when Cornwell’s ultimate loyalties are to Her Majesty’s government.

He’s wonderfully artful with Errol Morris and he occasionally plays the card of saying that any massive interrogation like this one will always at some level be a quest for the self and its enigma on the part of the interviewer. He also faffs around with a tremendous gravity about there being no true self, for anyone perhaps, certainly for himslef.

Only occasionally do you get him laughing or smiling but when you do you see how he could inspire love that would move mountains.

But he is a past master at this game of being the maestro of self-depiction but he leaves you reeling at the skill and depth of intelligence in this variegated and brilliant Browning monologue. At one moment it’s as if he drops every mask and says that people think he’s duplicitous. Well, you bet they do but this moment creates awe: it’s like a mirror held to a mirror.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in