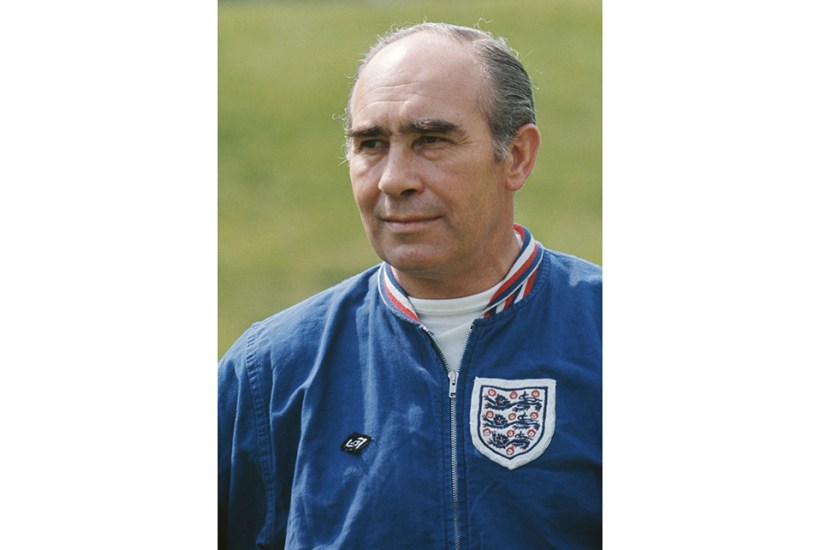

No better book about England’s victory in the football World Cup of 1966 and what followed it has ever been written. Duncan Hamilton’s Answered Prayers has the authority of a work of history and pulses with the narrative power of fiction. Its unlikely hero is Alf Ramsey. He emerges as a curiously complicated character through whom Hamilton tells his story.

This is not a tale of the glory of that sunny day. It is instead a kind of melancholy eulogy. England won despite English football’s powers that be – ‘unpleasant men’ such as the FA’s Sir Harold Thompson, a distinguished professor of chemistry and fellow of Trinity College, Oxford, who ‘had the eyes of a dead fish’ and ‘was the kind of snob who looked down his stubby, patrician nose at anyone who didn’t possess either a title or a fortune’.

Players and coaches were treated more or less like chattels. The Football League’s Fred Howarth, who ‘imprinted his dour personality on the League the way a fossil imprints itself on rock’, had opposed abolishing the maximum wage for footballers, and didn’t much care for floodlights or Europe or television (‘the idiot box’). These attitudes were broadly shared by chairmen and boards throughout the country. They were what Ramsey (whose childhood had been one of genuine poverty) and his players had to overcome – a challenge as great as that presented by teams from Brazil, Portugal and West Germany.

At Ipswich Town things were different. Having retired from a playing career at Spurs and for England, Ramsey was appointed manager of the Third Division club in 1955. He found in the chairman, the eccentric John Cobbold, heir to the Tolly Cobbold beer fortune, an enthusiastic supporter, who gave him everything he wanted, most importantly freedom and respect. By 1962 Ramsey had made Ipswich champions of England. He became the obvious choice to replace the hapless Walter Winterbottom following another lacklustre England showing at the 1962 World Cup in Chile.

Ramsey lacked the presence of Bill Shankly or Matt Busby or Brian Clough. He was diffident in speech, especially after losing his cockney brogue, often sounding like ‘someone from an amateur dramatic society wrestling with his lines in a Noël Coward play’. Hamilton writes that ‘Ramsey regarded how he “felt” as no one’s business apart from his own’. This takes us to a sizeable difference between now and then, and not just in terms of the way we think, or indeed feel, about football. Ramsey said of himself: ‘They say I’m remote. Difficult to get to know. I think this is fair.’ It is hard to imagine anyone with a public profile saying such a thing today.

Names to conjure with: Banks, Cohen, Wilson, Moore, Charlton J., Stiles, Ball, Peters, Hunt, Charlton R., Hurst. It wasn’t easy putting that famous team together. Ramsey was less concerned about results than with finding the perfect combination of talents, ‘like a poet struggling for a rhyme’. He used dozens of players, and insisted on playing friendlies against serious opposition. A stickler for detail, he reassured his players that he knew what he was doing and that there was nothing arbitrary about his decisions. They were devoted to this apparently cold, unfeeling man, and one of Hamilton’s footnotes helps illustrate why. In the semi-final of the 1968 European Championship, against a brutish Yugoslavia team

Alan Mullery had one last chance to reciprocate – and so he took it, swinging his right boot into his assailant’s groin. In the dressing room afterwards, he expected Ramsey’s condemnation for his lack of discipline, but instead was congratulated for giving back to ‘those bastards’ a taste of their own cruelty. Ramsey paid the £50 fine that the FA – blind or ignorant to the injustice – handed to Mullery, denying him an appeal.

One player was perhaps less devoted. Possibly the deadliest finisher in English football history, Jimmy Greaves was ruthlessly left out of the final team. He famously descended into alcoholism, perhaps as a result of his disappointment, and as famously pulled himself out of it to become celebrated as an idiosyncratic and entertaining TV pundit. His subsequent success was in ironic contrast to most of those who did play.

The final whistle in 1966 comes a little after half way through the book. It is by no means all over. Hamilton takes us to Dudley town hall for ‘An Evening with Sir Geoff Hurst’ last year. The venue is a quarter full, mostly men of a certain vintage. Hamilton sinuously weaves the fates of Hurst’s 1966 team mates in and out of an event both celebratory and poignant.

There is a sad, downward trajectory of many of the players concerned. Six were to suffer from dementia. Moore, Ball and Cohen all died before the age of 65. Gordon Banks lost an eye in a car crash. After Ramsey’s sacking in 1974 following England’s failure to qualify for the World Cup, ‘people regarded the men in charge of the FA as an unpleasant, vengeful and ungrateful bunch of heartless incompetents’, and Hamilton is in no doubt people were right. Ramsey, when subsequently attending matches at Wembley, always chose to sit as far away from the FA grandees as possible. He was a man who ‘could not fake sincerity and lacked the stagecraft to learn it’. He died in 1999, suffering from dementia like the majority of his players. Of the 92 invitations to his memorial service in Ipswich sent to Premier League and Football League clubs, only five were accepted.

Despite this sad end, Answered Prayers is a feast of a book, constantly engaging, and a proper contribution to the history of the period. The World Cup was as big as the Beatles. Names from the age dot the text –David Bowie, Philip Larkin, Mary Quant, Twiggy, George Best, Harold Pinter, A.J. Ayer. Through it all there is a distant suggestion of the author’s own approaching mortality, which may contribute to what makes this marvellous book genuinely affecting.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in