Shortly after the first Covid lockdown ended, doctors began to notice something so strange that at first they struggled to explain it. There appeared to be a sudden rise in the number of children being referred with Tourette’s syndrome.

Tourette’s is a rare neurodevelopmental disorder characterised by repetitive, involuntary movements or sounds called ‘tics’. While mild tics are relatively common in children, specialists suddenly started seeing large numbers of children displaying complex and debilitating symptoms. Dr Alasdair Parker, president of the British Paediatric Neurology Association, said in 2021: ‘The most severe tics disorders I have seen over the past 20 years have all presented in the last five months to my practice.’ Specialists were using the word ‘explosion’ to describe the numbers they were seeing. There were reports of adolescent psychiatry units that would expect to see four or five new cases a year recording that number in a week.

Even stranger, although Tourette’s is usually more common in boys, young girls accounted for most new cases. A paper published in the Lancet earlier this year found a more than fourfold increase in the disorder among young women. This bizarre phenomenon suggested that something was happening that wasn’t following the usual pattern – that wasn’t purely neurological.

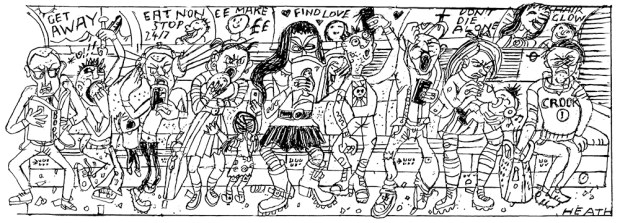

It became apparent that the Covid lockdowns had created a perfect storm. The exact cause of severe tic disorders like Tourette’s has long been debated. It is likely that there are genetic factors and parts of the brain controlling movement are involved, but undoubtedly stress, anxiety and depression play a role. What doctors uncovered was that for several years before the pandemic an online community had been growing where those with Tourette’s had been posting videos of their tic attacks as a form of support for one another. What happened during the pandemic was that young people, stuck indoors for months on end watching social media like TikTok, had stumbled across these clips. This, combined with the severe stress and anxiety of lockdown, fuelled a stratospheric rise in cases. The more people developed tics and posted it online, the more people saw it and developed tics themselves.

Severe tic disorders are rare, so it’s no surprise the sudden ‘explosion’ of children presenting with them got attention. But the rise is just one manifestation of the disastrous effect our response to the pandemic had on the mental health of an entire generation.

The rise in Tourette’s is relatively easy to study but the more general impact on children’s mental health is far harder to quantify. For every child referred to mental health services with depression, there are many more sitting at home, alone in their rooms, withdrawing from the real world. They struggle at school and miss out on opportunities. These cases are often not picked up by studies, yet they represent the shaming legacy of lockdown. The number of children missing school has doubled since before the pandemic. Lee Elliot Major, professor of social mobility at the University of Exeter, says that there has been a ‘post-pandemic tidal wave of school absences’ and warns that ‘the seriousness of this cannot be overstated: not turning up for school is the surest way of ruining your future life prospects’.

In July, the Institute for Fiscal Studies and UCL published the first study of its kind into the impact of lockdowns on children. It found that the effect of lockdowns extended beyond lost academic progress. Emotional development and social skills were harmed in just under 50 per cent of children. The rates of referrals for children with eating disorders has doubled. There are rising numbers of children self-harming. Over the pandemic’s course, the number of young people with probable mental health problems soared, jumping from an estimated 12.1 per cent of children in 2017 to 18 per cent last year. In study after study we have seen how children – especially those aged between seven and ten – bore the brunt of our lockdowns.

And that’s before we even factor in the horrific rise in child murders and cases of abuse thanks, if we are brutally honest, to social care and health professionals abandoning many vulnerable children to the mercy of drug-addicted or violent parents. Behind closed doors – while the metropolitan elite, who so vociferously called for harsher lockdowns, sat in their gardens having Zoom cocktails with their families – these children had to endure torment and torture.

At the beginning of last month, the NSPCC warned that Covid restrictions at the height of the pandemic were used ‘as a cover’ by abusers to hurt children as the usual safeguarding methods at schools and clubs were absent or moved online. Some 20,000 children dropped off school rolls during lockdown and are still unaccounted for.

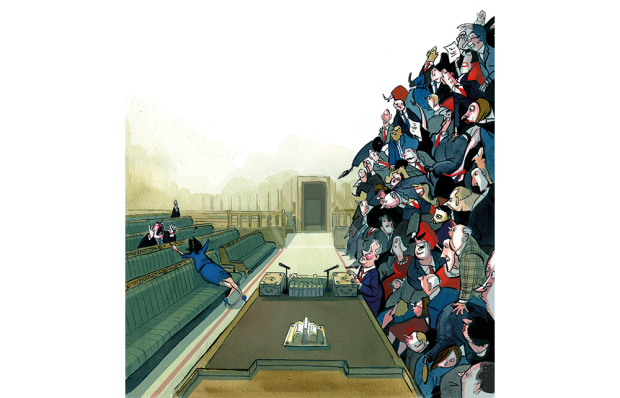

Many others were simply neglected. Some not only failed to progress but actually regressed. Teachers spoke about children returning to school, barely able to hold a knife and fork, their literacy had deteriorated and some were even wearing nappies again. And despite all the emerging evidence of the heart-breaking damage we have done, there are still those who insist we should have locked down earlier and harder. They cling to the belief that a blanket lockdown was the right thing to do even though it became evident very early on that children were the least at risk from the virus and had the most to lose from lockdown. And it was all for nothing anyway. A meta-analysis led by Johns Hopkins University showed that lockdown restrictions caused just 0.2 per cent reduction in virus deaths.

What have we done? We panicked and put in place a social experiment never tried before. Teachers’ unions, the NHS, social workers who should have been championing children turned their backs on them. And all the time the police busied themselves with penalties for people sitting on park benches.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in