It’s a convoluted title for a book, but then Lafcadio Hearn – a widely travelled author and journalist who earned his greatest fame as an interpreter of Japanese horror stories – led a convoluted life. Born in 1850 from a difficult marriage between an Irish officer-surgeon and a wildly unpredictable noble-blooded Greek woman (his middle name, Lafcadio, was adopted from Lefkada, the name of the island where he was born), he was quickly abandoned by both. His mother ended her life in an asylum; his father remarried and died young of malaria. Hearn went on to be yet again abandoned by the great-aunt who raised him, and spurned by the impatient Catholic priests to whom he was entrusted for an education. (He developed a life-long hatred for Catholicism, while cultivating a loose, long-lasting affection for Buddhism.)

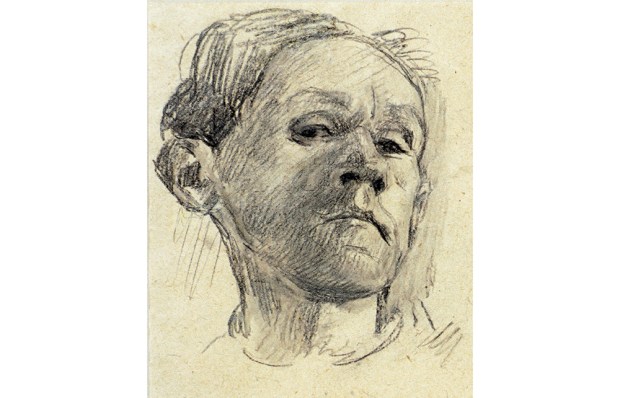

He lost his left eye to a youthful accident, and spent the rest of his life shyly turning his disfigured profile away from attention. The greatest pleasures of his youth were the diverting stuff he found in books, legends and tall tales told him by servants and care-givers; the more fantastic those stories, the better. In addition to the tales of Poe and Hoffmann, Hearn was fascinated by an illustrated childhood book of Greek gods and goddesses, of which he later wrote: ‘After I had learned to know and love the elder gods, the world again began to glow about me. Glooms that had brooded over it slowly thinned away.’ Like those other English-speaking fabulists Arthur Machen and Lord Dunsany, Hearn never trusted orthodox churches and governments; he was, at heart, a pantheist.

His love for books about timeless, unearthly creatures sustained Hearn through many years of calm, intrepid journeying. Sent to London to live with his great-aunt’s former servants, he wandered the streets as fascinated and appalled by the noise, crime and dirt as Dickens had been before him. When he moved to the United States in 1869, he was drawn to similarly dangerous urban areas in New York City and, later, Cincinnati, where he developed – after many financial difficulties – youthful fame as a night-beat reporter and columnist for the Cincinnati Enquirer.

One of his editors later recalled him as ‘a quaint, dark-skinned little fellow, strangely diffident, wearing glasses of great magnifying power and bearing with him evidence that Fortune and he were scarce on nodding terms’. Even more notably: ‘He was poetic, and his whole nature seemed attuned to the beautiful, and he wrote beautifully of things which were neither wholesome nor inspiring.’

The subjects that invigorated Hearn’s readers (as well as Hearn’s own imagination) included city hangings, a pitchfork murder in which the dead victim was subsequently flung into a boiler, human autopsies, the murder of a two-year-old child, body snatchers in cemeteries, crooked spiritualists and a woman popularly known as the Queen of Voodoo – not to mention a back-alley abortionist and fortune teller who ran a brothel under the name of Madame Sidney Augustine, whose eventual arrest led to the discovery of a dead foetus on her property wrapped up in one of her old silk dresses. But even in his journalism, Hearn – normally soft spoken and unassuming – was already preparing for the next adventure: at one time he dressed up as a woman in order to report on a for–women-only political lecture, and at another, he strapped himself to the back of a steeplejack so he could be carried to the top of the city’s tallest cathedral to describe the view.

For a shy man who preferred his private imagination to a world that never provided him with a lasting home, Hearn was a transgressive personality. And when he transgressed one of the hardest, fastest boundaries in white, middle-class Cincinnati by marrying an African-American woman who ran his boarding house – a former slave named Mattie Foley – the marriage didn’t last much longer than Hearn’s reputation, which was so badly smeared that he lost his job at the Enquirer and moved to New Orleans. Eventually he became one of the first historians of Creole cooking, and spent his evenings in dockside bars collecting the songs of black entertainers.

Hearn had lived his early life as an outsider; and it was among outsiders that he felt most at home. But while his authorship of the first American books on Creole cooking might have led him to become a sort of early version of Anthony Bourdain, his was a permanently restless, always shifting soul which could never quit travelling – or seeking to meet and understand other outsiders like himself. Whenever he established a home in one place, he set out for another, producing several remarkable books about his experiences in the West Indies before landing in the furthest place his restless imagination could carry him – Japan.

It was there that he found his happiest home in the western castle city of Matsue, a place that his great-grandson Bon Koizumi describes in the Foreword to Steve Kemme’s enjoyable new biography as ‘steeped in myth … dotted with ancient Shinto shrines’ and populated by ‘devout people who prayed to the rising sun and moon while clapping their hands’. Hearn called it the ‘Chief City of the Province of the Gods’, for instead of the human, earth-bound people he couldn’t depend on as a child, he spent his increasingly happy adulthood in the imaginative company of these vast and more dependable spiritual forces.

There has long been a good deal of interest in the indefatigable journeyings of Lafcadio Hearn; and there have been many good biographies of his life before this latest (and very good) one – but there is probably no better time than now to appreciate what his great-grandson calls Hearn’s ‘philosophy of tolerance’ for other people, other cultures and other religious traditions. (In fact, it’s possible to argue that Hearn enjoyed most cultural traditions more than he did his own.) His second marriage turned out to be a long, productive and loving one, even though it started out as an arranged betrothal with a young woman whose destitute family and servants came to share the modest salary of an English teacher at a rural college.

Hearn went on to become a much-loved teacher and in his final years attained fame for doing the things he did best, such as simply appreciating, and translating into English, the story-telling traditions of another culture. His travel essays and philosophical reflections about Japan’s modest people in books such as Glimpses of Unfamiliar Japan (1894) and Out of the East: Reveries and Studies in New Japan (1895) were popular both in the West and in the East, where Hearn eventually adopted a Japanese name (Koizumi Yakumo) in order to protect his family’s inheritance after he died. In his most famous works, such as Kwaidan: Stories and Studies of Strange Things, he translated and preserved the numerous ghost stories he collected through conversations with the lowliest people he met – servants, fishermen and shop-keepers. These stories remain some of the most beautifully written strange stories ever recorded. In many ways, Hearn’s greatest gift to literature was his innate ability to simply listen to the people he met.

For while Hearn may be largely remembered for his ghost stories about horrific supernatural events – headless and faceless demons running loose in country villages, corpse-devouring goblins and the spectral convenings of dead warriors – his ghostly landscapes are often welcoming places as well. In these wide-open, starry-lit vistas, ghosts don’t simply haunt the living: they fall in love with and marry them, give birth to and breastfeed their living babies, raise families, and help feed the in-laws. They are, in fact, a lot better (and more dependable) than many of our so-called ‘living’ people could ever hope to be.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in