When Henry James moved to Lamb House in the Sussex coastal town of Rye, he admitted that he could hardly tell a dahlia from a mignonette: ‘I am hopeless about the garden, which I don’t know what to do with and shall never, never know – I am densely ignorant.’ He sought advice from the artist and designer Alfred Parsons and fortunately Lamb House already had a gardener, George Gammon, to do all the work. When Gammon won prizes at local horticultural shows, James was delighted: he was a vicarious gardener, more comfortable at his desk in the Garden Room than with his hands in the soil.

Thomas Hardy was at the other end of the gardening spectrum. Born in Dorset in the thatched cottage at Higher Bockhampton that his grandfather built, he grew up helping in the kitchen garden and orchard, trading apples for access to books with a friend whose father was a bookseller in Dorchester. When Hardy designed a new house in Dorset for himself and his wife Emma, he planned the garden before Max Gate was built. There were three distinct garden areas, including one where his plays could be performed, surrounded by woods that he helped plant with pine, yew, laburnum, elder, beech, bay, box, laurel and plane trees. ‘It was the trees that Hardy really cared about,’ Jackie Bennett writes in her sumptuous coffee-table book. Hardy’s description of Giles Winterbourne’s gentle hands spreading out roots before planting saplings in The Woodlanders reflects his personal experience.

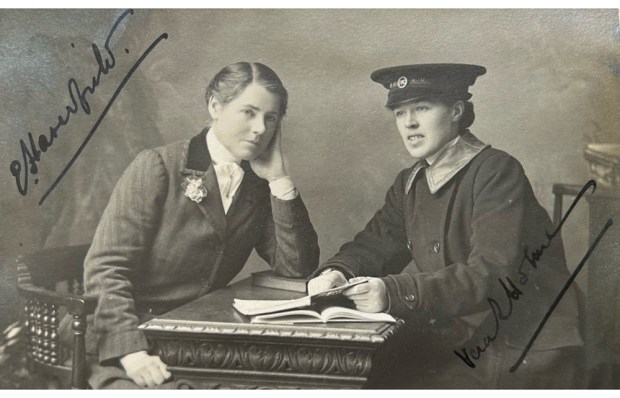

Between the extremes of James and Hardy, Bennett describes 26 other writers’ gardens, some from outside the UK, and provides up-to-date visitor information. Each alphabetically arranged entry is generously illustrated with photographs by Richard Hanson, and accompanied by a short note on the ‘Writer in Residence’. This structure allows the writers to be glimpsed briefly, passing through beautiful spaces that have outlasted them.

Sometimes the writers transformed their gardens into words – Frances Hodgson Burnett immortalised the grounds at Great Maytham Hall in The Secret Garden, Rudyard Kipling caught the spirit of his Sussex garden at Bateman’s in The Glory of the Garden – but all the gardens have matured and rejuvenated beyond the tenure of the resident writer. Apples are a recurring theme. Louisa May Alcott referred to the drafts of her novels as ‘green apples’. When her parents bought an old farmhouse in Concord, Massachusetts, and named it Orchard House, the garden there inspired the garden in Little Women, where each sister has her own section of flower-bed. Since the 1990s the Orchard House grounds have been carefully restored with new plantings of heritage apple trees that would have been grown in Louisa’s childhood including the eating apple ‘Baldwin’ and the cooking apple ‘Rhode Island Greening’.

Karen Blixen spent most of her life in Rungstedlund, her parent’s manor house north of Copenhagen. She returned there after her divorce from Bror von Blixen-Finecke, with whom she had lived in Kenya, and from whom she had contracted syphilis. When she was in her seventies a local gardener cultivated and named an eating apple after her: Malus domestica ‘Karen Blixen’. Rungstedlund was opened to the public in 1991 so visitors can appreciate the writer’s work as a conservationist alongside her accounts of big game hunting in Out of Africa.

In Jean Cocteau’s garden at Milly-la-Forêt there is a moat and a partially walled verger: ‘Four squares of lawn divided by paths lined with trained apples and pears.’ Among the trees are heritage varieties ‘Reine des Reinettes’, ‘Belle Joséphine’ and ‘Beurre Hardy’. Cocteau grew grape vines against the walls which still thrive and underplanted the trees with irises and herbaceous peonies. When he died in 1963, Cocteau left the house and garden to his gardener, who lived there until 1995, when he died and was buried next to Cocteau beneath the floor of the chapel.

At Yasnaya Polyana, his family estate 130 miles south of Moscow, Leo Tolstoy planted 200 young apple trees: ‘And for three years I dug around them in the spring and the fall, and in winter wrapped them with straw against the hares.’ Bennett explains that ‘for Tolstoy, apple blossom was a symbol of renewal and life. When the blossom came, everyone – from the landowners to the peasants – joined in this feeling of wellbeing and good fortune’. The weblink for visiting Yasnaya Polyana is included under ‘Garden Visiting Information’. Around 100 of the apple trees planted in Tolstoy’s lifetime still bear fruit. Perhaps there will be peace again in our lifetimes and it will be possible for foreigners to visit and see the apple blossom as Tolstoy would have wished.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in