Twelve months after Sir Mark Rowley embarked on a mission to re-boot the Metropolitan Police following a wave of scandals, the force has revealed that it has suspended or placed work restrictions on a thousand of its officers.

More than 200 are currently suspended and 860 are on ‘restricted duties’ while criminal or misconduct allegations are investigated – taken together that’s as many as people as work in a small constabulary. In addition, there has been a 66 per cent increase in dismissals for gross misconduct – with 100 in the last year, and 300 more hearings in the pipeline. Scotland Yard says that before long, 60 cases of alleged misconduct or incompetence will be heard each month with a number of Crown Court trials due to take place as well, including those of two Met officers charged with rape.

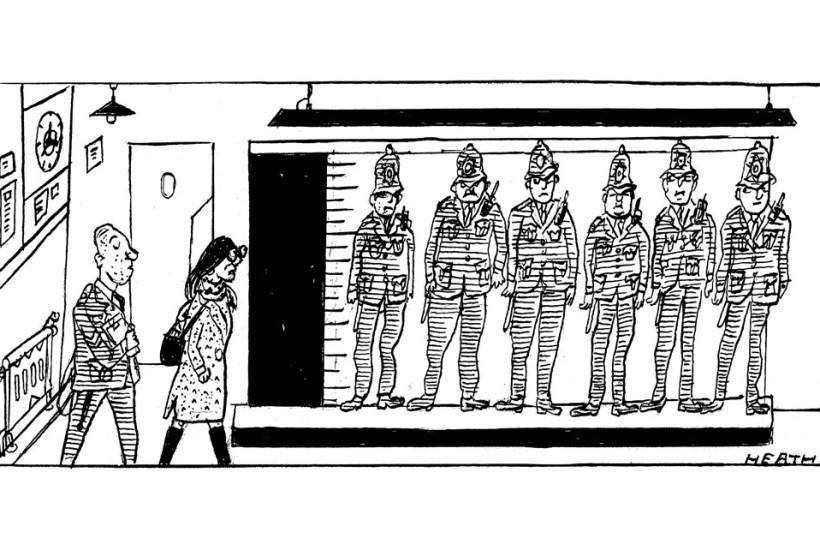

The groundwork for this mass investigation of Met staff began shortly after the Commissioner took office last September, when he suggested that there were ‘hundreds’ of officers who shouldn’t be there. This was striking at the time. Can you imagine the chief executive of a major company saying that about their own employees?

Rowley then transferred 150 detectives into a new anti-police corruption and abuse unit tasked with examining internal wrongdoing. It was a statement of intent and an extraordinary investment of personnel and resources, particularly given how stretched public-facing parts of the force are. But it was necessary – as Baroness Louise Casey’s review later demonstrated.

Established after Wayne Couzens, a Met officer, had been jailed for the kidnap, rape and murder of Sarah Everard, Casey’s report exposed a rotten culture of defensiveness, denial and systemic bias within the force. According to Casey, predatory behaviour among officers wasn’t being picked up on, vetting and supervision had been allowed to slide and staff who complained were targeted. ‘There are too many places for people to hide,’ she wrote.

The days after her findings were published were dominated by a row over Rowley’s refusal to accept that the term ‘institutional racism’ applied to his force. But on the seventh floor of New Scotland Yard the leadership had already embarked on the biggest overhaul of standards for 50 years.

The new anti-corruption and abuse unit set up three operations, codenamed Onyx, Dragnet and Trawl, to carry out detailed checks on the Met’s 47,000-strong workforce and re-examine previous allegations of domestic abuse and sexual offences against serving officers and staff. A hotline was launched to report police wrongdoing and a new approach was devised to expel those who failed to comply with vetting requirements. They have all contributed to the startling number of internal investigations now underway involving those 1,000 officers.

Numerically, it provides firm evidence of Rowley’s commitment to change, but it also highlights a wider problem for the country’s biggest police force. It will take at least two, probably many more, years to get through all the cases, during which time the publicity will lead to more damaging headlines and potentially a further erosion of trust and confidence in the force.

The latest figures, collected by the London Mayor’s Office for Policing and Crime, show trust levels in the Met are still on the decline and are now ten percentage points lower than they were before Sarah Everard’s murder in March 2021, at 70 per cent. In some inner London boroughs and among black and mixed ethnicity communities, trust levels are between 50 and 60 per cent. Even more concerning is the proportion of Londoners who believe the force is doing a ‘good job’. In 2018, around two-thirds said it was, now it’s less than half.

Critically, the upheaval in the Met and the flow of bad headlines are affecting efforts to recruit and retain officers. As part of the government’s programme to restore police numbers to the level they were in 2010, funding was made available for Scotland Yard to hire an extra 4,557 officers by the end of March this year. Although the workforce did expand significantly, the force fell 1,089 short of the target with the money for the ‘missing’ officers withdrawn. Sir Mark admitted that the recruitment difficulties were partly due to the ‘reputation of the organisation’ – and since then the problems appear to have worsened.

By the end of July, the number of officers, based on full-time equivalent roles, had fallen by 141 to 34,362 with applications for constables down to around 40 per cent of the level required. More than 200 officers are departing every month which means the force, with acute cost-of-living pressures in London and fierce competition from other employers and sectors, is destined to carry on shrinking. Earlier this month, the Commissioner said he feared Met recruitment was ‘going backwards’ and they would soon be 1,500 officers below the 35,000 he has been aiming for.

The more energy the Met puts into rooting out rogue cops, the more stories become public and the less attractive the force looks – to the public and those considering a career there. Deputy Assistant Commissioner Stuart Cundy, who’s leading the anti-misconduct drive, described it as a ‘paradox’, but he is under-stating the problem. It is in fact a dangerous spiral. Changes to the police misconduct system, intended by the Home Office to simplify procedures and make it easier to sack officers, cannot come soon enough – but they must go further. Officers who fail vetting checks and cannot be found an appropriate and genuine role should face immediate dismissal and the Ministry of Justice needs to consider ring-fencing courtrooms and judges to try cases involving the police. Some cases currently aren’t due to start until 2025.

Change is happening quickly in the Metropolitan Police. But unless the misconduct and criminal justice systems move faster, the force is going to be stuck with officers who shouldn’t be there and negative headlines for years to come.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in