Lauren Groff writes to alleviate her angst about aspects of life she finds hard to confront. Climatic disaster, misogyny, spousal death, flawed utopias and pandemics have all fuelled the plots of books as disparate as Fates and Furies, her 2015 contemporary two-hander about marital verisimilitude, and Matrix, which features a 12th-century feminist abbess based on the little-known poet Marie de France. Yet neither is a bleak read; indeed, Barack Obama selected Fates and Furies as his 2015 pick. Groff’s intoxicating 2018 story collection Florida threw the strains of motherhood into this mix: the mother in ‘Ghosts and Empties’ who laces her running shoes to pace the streets because she has ‘somehow become a women who yells’ and she does not want to become a woman who yells remains seared on my brain.

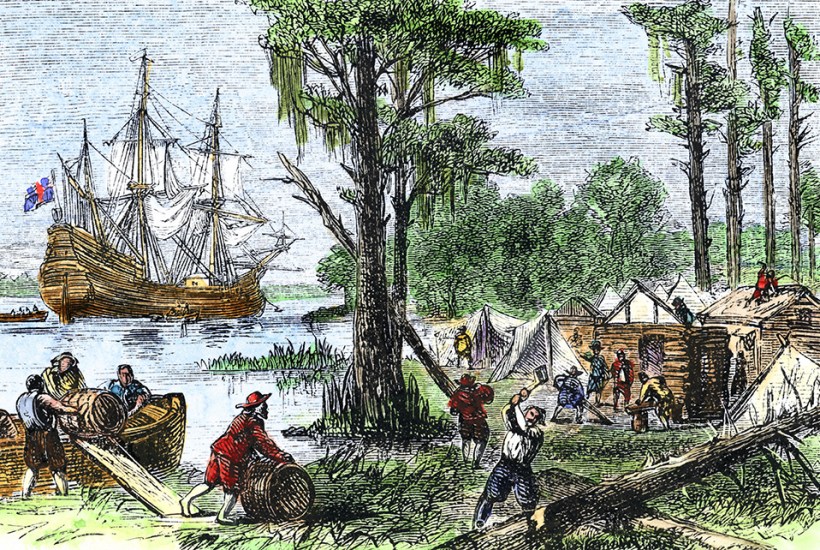

In her fifth novel, The Vaster Wilds, the American author turns her attention to colonial injustice in a prophetic tale about a servant girl who flees a blighted English settlement in 17th-century Jamestown. The girl, who has committed an unnamed sin, is emaciated after months of famine.

‘Into the night the girl ran and ran, and the cold and the dark and the wilderness and her fear and the depth of her losses, all things together, dwindled the self she had once known down to nothing.’ Groff writes in prose that sparkles like the forest after the storm of freezing rain that forces her heroine to take shelter under the roots of an upturned elm.

Like Marie in Matrix, the girl has visions but hers are fever dreams, plaguing her nights and confusing her days, a literary device Groff uses to flash back to the girl’s former life in England and to cast what passes for plot further forward. The girl, who has had many names but none that ‘had ever felt fully hers: Lamentations Callat, Girl, Wench, Zed’, was plucked from the parish poorhouse aged four to serve a mistress with a cruel son and a daughter whom the girl loved deeply. It was the mistress’s second husband, a greedy minister who longs for ‘new-world glory’, who forced them to make the crossing under the guise of bringing god to the people already there.

As the girl grapples with nature to survive, she realises the colonisers’ folly. ‘How in coming to this country, her fellow Englishmen believed they were naming this place and this people for the first time, and how it conferred upon them dominion here in this place although, she was now surprised at her thought, surely the people of this place had their own names for things. But one name takes precedence over another, and so the wheel of power turned.’ Her revelation that ‘this place and these people here did not need the English to bring god to them’ is salutary.

This beautifully written, soulful book is partly a fable and partly a treatise on greed: an exhortation for mankind to be satisfied with his lot, something we would all do well to heed.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in