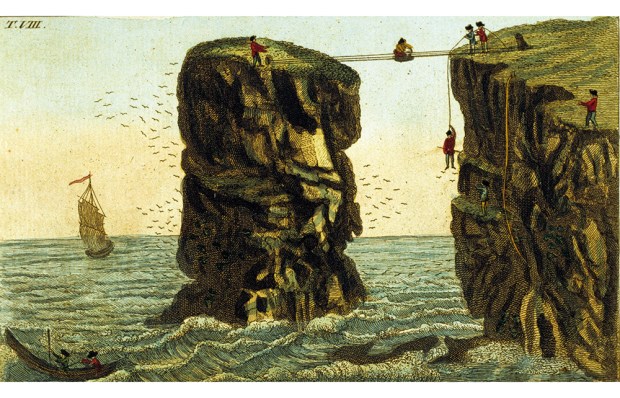

There is an ancient comment (on the work of a grammarian with the terrific moniker Dionysius Thrax) that the performers of the Iliad and the Odyssey changed costume according to which poem they were reciting: a dark blue crown for the sea of the Odyssey, red for the blood of the Iliad. Emily Wilson, whose brisk and clear-eyed translation of the Odyssey became a bestseller, has now switched her sea-blue crown for her blood-red one. Even the covers of the two books – the Odyssey had a blue-dominated cover depicting the Minoan fresco of ‘Ladies in Blue’; the Iliad is red and gold, with an image of Thetis giving Achilles his new helmet – reflect the shift.

We tend to think of the Odyssey as the taller tale of the two – full of ogres and witches and sea monsters – and of the Iliad as relentlessly grounded in the dust of battle and the ‘plights and gripes’ of Achilles. But to read (or reread) the poems is to be reminded of how wrong this is. The Odyssean stories of Cyclopes or sirens turn out to be told around the campfire by an expert storyteller, the sole survivor of a shipwreck who has no witnesses to back him up. Odysseus’s real journey is deeper and deeper into the homespun reality of a Greek island only good for raising goats.

The Iliad on the other hand is always stranger than we remember. Achilles, the focal character, may be human, his mortality the essential plot point in this episode from the ninth year of the Trojan war; but he is the son of an immortal mermaid (who sometimes visits him on land in the form of a mist) and was educated by a centaur physician. His war kit is composed of divine gifts, including god-made armour and a pair of immortal horses, one of whom occasionally speaks. In battle, gigantic gods walk among the fighters, sometimes whisking off their favourites to safety in a cloud of invisibility, or getting grazed themselves. Rivers are sentient and brother rivers talk to one another. In the halls of Olympus, we find the smith god, Hephaestus, a kind of limping mad scientist, busy fashioning tripods that will roll about on their own, like three-legged Roombas, and assisted by a team of golden fem-bots. The Iliad is deeply weird, and its world utterly foreign to us, yet it is also centred on human mortality and suffering and the brutality of violence and the tragedy of loss. The Odyssey has fun fantasy elements, but the Iliad is steeped in an ancient magical realism: the otherworld of the gods coexists with the anatomical accuracy of puncture wounds, as bronze cuts through livers, slices off tongues, pierces bladders, and warriors hold their own spilling intestines in the basket of their arms. It is in some ways a more difficult and less accessible poem.

Wilson’s Odyssey stirred up an energetic discourse (particularly online): was it too brisk and clear? Was it – and here the arguments are less easy to follow – too ‘woke’? (Wilson was uncompromising in calling enslaved people, especially women, slaves, and not, say, handmaidens.) But arguably the most radical thing about the translation was that it conveyed the Greek in a strict iambic pentameter (the meter of your average sonnet), not the ‘loose five beat line’ or ‘loose six beat line’ favoured by epic translators for conveying Greek’s unrhymed dactylic hexameter since the mid-20th century.

Wilson has approached the Iliad slightly differently. Again, the translation is uncompromisingly metrical, strongly rhythmic and designed to be read and heard aloud, but Wilson has allowed herself to expand beyond the line-for-line scheme of her Odyssey, giving her more room to include all the facets of the Greek, the epithets, the patronymics, and more lyrical latitude – including flexing more luxuriously Latinate and polysyllabic words. The Iliad is already a long poem – it is nearly 3,500 lines longer than the Odyssey – yet somehow the result of giving the poem more breathing room is, counterintuitively, to speed up the relentless action while letting our attention slow down and focus on – to really listen, I want to say, rather than ‘read’ – what is happening.

There is a feeling, in the hyper-reality of the fighting scenes, of the four days of battle unfolding in real time. The poet often pauses in the midst of the gore to focus on not just individual deaths, but individuals: lives flash before their, and our own, eyes, right before everything goes dark. Consider poor Othryoneus, cut down by the Cretan Idomeneus:

He [Idomeneus] slaughtered Othryoneus,

who had

only just heard the news about the war,

and come from Cabesus to Troy. He sought

Cassandra, Priam’s daughter, as his bride –

the loveliest of all of them. He brought

no bridal gifts, but swore he would perform

a mighty deed to win her hand…… The boy was wearing

a breastplate made of bronze, which did

no good.

The spear pierced through the middle of

his belly.

Wilson achieves her register – at once plain spoken and slightly removed from everyday speech – partly by studiously avoiding contractions and allowing for metrically convenient epicisms like ‘mighty’, mixed in with natural-seeming phrases like ‘only just heard the news about the war’. The effect is not so much to bring the characters of the Iliad into the contemporary sphere, as to bring us into theirs. ‘Loveliest’, ‘deed’ and ‘to win her hand’ have something of the fairy tale about them, but these touches feel ironic rather than clichéd: Othryoneus will not live to marry the princess, and the beautiful princess herself will end up raped, enslaved and murdered. Reviewers of translations like to cherry-pick favourite or famous passages for comparison, but the true test of a translation of a long work is what it does in the connective tissue and the longueurs, the recitatives rather than the arias.

It is impossible, really, to mess up certain scenes – how can we fail to be moved by Hector’s baby, in its mother’s arms, being frightened by Hector’s horse-hair-plumed helmet, or touched by the parents smiling at this baby’s reaction, or chilled by our knowledge of the desolate future, in which father will be killed, mother raped and enslaved, and baby dashed from the walls of Troy? Wilson has written engagingly about her translation of this famous passage, which concludes:

With these words,

he gave his son to his beloved wife.

She let him snuggle in her perfumed dress

and tearfully she smiled.

‘Let him snuggle’ seems just right here – snuggle is tactile and visual. Translations have a way of being influenced in their interpretations by other translations. With Wilson, however, her constant wrestling face to face with the Greek uncovers fresh readings (the folds of a dress here, rather than the bosom itself, as it is often rendered), and her notes on the Greek are well worth stopping for. (The book is replete with maps, genealogies, notes and a glossary with pronunciation guide.) She is alive to suggested metaphors, as when Hera weaves a plan: ‘How then could I not stitch a quilt of ruin’, a delicious phrase.

When we think of Homeric style, we probably leap first to the epithets – those descriptors that tend to go hand in hand with various nouns, whether it be the wine-dark sea or rosy-fingered Dawn. Poetic to us, some of these are little more than metrical filler, such as horses having a single hoof rather than cloven feet: the joint phrase (single-hoofed horses) is perhaps more, well, more gallop-y. Sometimes Wilson turns a phrase over in the light to get different effects: ‘winged’ words might be ‘words take flight’ or ‘words flew out’, etc. Apollo, the far-shooting god (his arrows are responsible for the plague that begins the poem), is sometimes here ‘the god of distances’. Sometimes she scrubs a cliché clean, as with Briseis of the lovely cheeks (‘Sweet cheeks’ Briseis, my Greek husband jokes, as if she were a gangster’s moll), who becomes here ‘fresh faced’ Briseis. As in her Odyssey, Wilson wisely, though, hews to the famous ‘wine-dark’ (of the sea, or, here, also of cattle) for oînops. Let’s face it, there’s no improving on wine dark, and the truth is no one really knows what oînops means – dark like wine, purple, red faced as a drunk? Though Wikipedia claims it is ‘traditional’, the phrase ‘wine-dark sea’ for Homeric translations only dates to Andrew Lang and Samuel Butcher’s prose Iliad of 1893; perhaps they fetched it dripping out of Charles Kingley’s 1858 poem ‘Andromeda’.

Wilson has said that she is an Iliad person rather than an Odyssey one. And I have to say that for all that I enjoyed her Odyssey, I have been even more absorbed by her Iliad, and found myself, for all that I know how everyone’s fates shake out, crying one afternoon for Andromache, who is busy heating up a bath for her husband for when he comes home from the battlefield:

Up in an inner chamber of the house

she wove a double-layered purple cloth,

and in it stitched elaborate designs.

she called the house slaves with their

braided hair

to heat a mighty tripod on the fire,

so that the washing water would be hot

for Hector when he came back home from

battle.

Poor fool! She did not know that very far

from any bath, he was already dead.

Later, in the Greek camp, Hector’s murderer, Achilles, having accomplished his goal of avenging his companion, Patroclus, refuses to bathe until Patroclus is buried:

And when they reached the hut of Agamemnon

they told the clear-voiced heralds to set out

a mighty cauldron on the fire to try

persuading great Achilles to wash off

the blood and gore. He steadfastly refused.

Have I ever noticed these two baths before, both drawn up on the same day, for the dead fighter and the triumphant one?

It is a commonplace that this poem is about the ‘rage’ of Achilles. (Wilson translates this as ‘cataclysmic wrath’ to indicate that it is an almost super-human emotion.) But it might be more accurate to say that it is about how Achilles loses his humanity in outrage and grief, and then comes back to it again, and how everyone else in the poem is swept along in the consequences.

It’s a poem you read with your heart in your throat.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in