In Whitehall, visible to even the most short-sighted from the gates of Downing Street, stands an outsize statue of Lord Alanbrooke, the strategic adviser to Winston Churchill during the second world war. His job was to help the prime minister see the big picture and concentrate on the decisions that really mattered. This was no easy task. Churchill was both a tricky master and ‘tinkerman’, but Alanbrooke had Ulster blood and knew how to say no.

He also had a remarkable facility for explaining complex strategic problems in simple terms. There is good evidence of this in the BBC archive (and on YouTube) in a television interview he gave in 1957. Wartime strategy, he said, all came down to two decisions. First, should the Allies defeat Germany or Japan first? That was easily agreed: Hitler first. Second, should the Allies attack across the Channel and drive on to Berlin – the direct route the Americans instinctively preferred – or take a more indirect approach through the Mediterranean? This was the option favoured by the British, and it was their view that prevailed when Roosevelt and Churchill met at Casablanca in January 1943. There they decided that there could be no cross-Channel assault in 1943. Doing nothing was not an option. The main land effort would have to be in the Mediterranean.

By September 1943 the Allies had cleared North Africa, seized Sicily and were ready to invade Italy. Mussolini had fallen and the new government in Rome was on the brink of discarding its German alliance and surrendering. Intelligence suggested that when it did so Hitler would abandon the south of the country and withdraw to dig in up north. The Allies, therefore, landed near Naples, expecting an easy run to Rome. The intelligence was wrong. They had to fight every inch of the way, often in conditions their fathers would have recognised from Passchendaele. The bone-chilling rain and mud were endless and there was always another river or mountain to cross. One little village, San Pietro In fine, took more than a week and 1,500 Americans casualties to capture, and there were a lot of villages on the road to Rome.

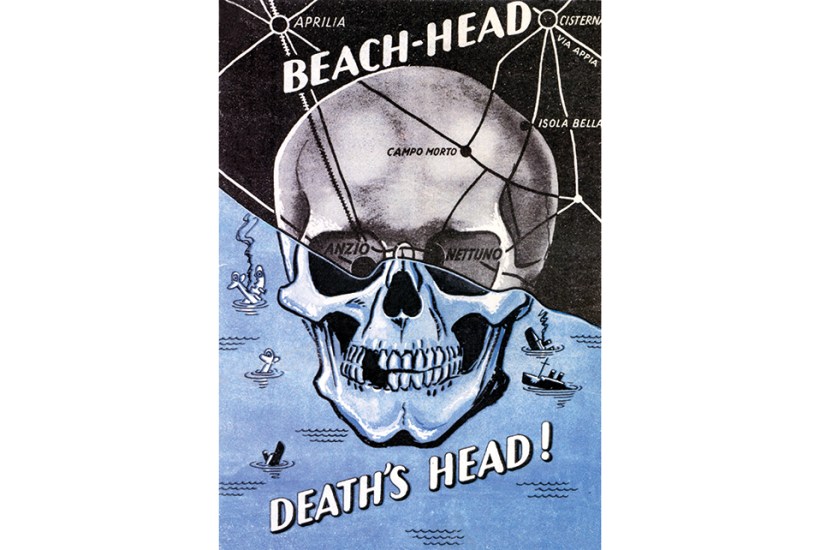

James Holland tells the story of the hard, bloody, muddy fighting that filled the rest of 1943 in this excellent book. This is not a well-known story. Just as D-Day and the campaign in north-west Europe has always attracted more attention than the war in Italy, so too the dramas of 1944 at Anzio and Monte Cassino have overshadowed the fighting of the previous autumn. Like much of the war, it is a story of Allied ambitions always outrunning capabilities, and so of recurring and inevitable disappointments, and of ferocious Allied firepower, resourceful and ruthless German defenders, and civilian homes and lives destroyed.

Holland knits together official records with the personal recollections of soldiers and civilians from both sides of the lines to present a picture of the fighting which blends top-down strategy with individual human stories. Above all, it is a picture of horror. At times this seems repetitive and stupefying, but that’s war for you. Then, at the end of the book, just when I thought I was numb and could be shocked no more, he tells the tale of a massacre so senseless and cruel that it remains unexplained to this day.

J.F.C. Fuller once described Italy as ‘a campaign which for lack of strategic sense and tactical imagination is unique in military history’. Holland argues, less extremely, that to launch the campaign without resourcing it properly was ‘dangerous, arrogant and did a great injustice’ to those who fought there. Anyone who watched British troops tasked to do the impossible in Iraq and Afghanistan will sympathise. The young men who served in Italy, however, knew and accepted that they were part of a sideshow, designed only to clear the way for D-Day, as the memoirs of the late Professor Sir Michael Howard, the eminent historian who won the Military Cross at Salerno, make clear. They fought and died all the same.

Holland wonders what drove troops from faraway Texas and New Zealand to keep going in the terrible conditions they faced. Howard would say it was two things: ‘the sheer bloody-minded determination to ensure that the Germans should suffer worse than we did’, and ‘defeating the Germans and getting home’. The physical courage he and his comrades displayed was matched only by the moral courage of their leaders, men such as Churchill and Alanbrooke, wrangling impossible choices and issuing orders which they knew would cause the suffering so vividly recalled in this book. The Savage Storm reinforces Holland’s reputation as certainly the busiest and probably the most popular military historian of the second world war working today.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in