We don’t know if the two teenagers who attempted a train robbery in Scotland this week knew that it was the 60th anniversary of the most famous one in British history. Given their failure – nothing was stolen and the charges include ‘malicious mischief’ – it seems unlikely. Either way, the train robbery of August 1963 remains secure in its title of ‘Great’.

Why did it fascinate us so much in the first place? Partly it was the zeitgeist timing (that year also saw Profumo, Beatlemania and JFK’s assassination); partly the amount stolen (£2.5 million, worth more than £40 million today); and partly the narrative of ‘plucky underdogs vs the police and banks’ – the last of whom were insured, except the Midland, which disdained the idea and so lost £500,000.

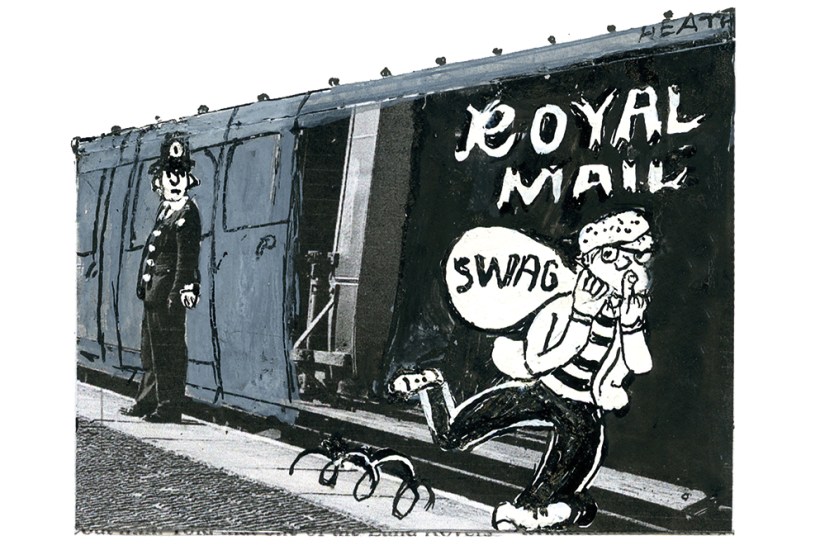

But mainly the robbery received its adjective because it’s a great story. The gang brought the train to its 3 a.m. halt in the Buckinghamshire countryside simply by placing a glove over the green signal light and attaching a battery to the red one. ‘Pop’, the retired driver brought along to shift the train to Bridego Bridge, where the cash-laden mail bags would be unloaded, couldn’t work the handbrake. The gang had already had their doubts about him. Told that one of the Land Rovers they were using was stolen, he replied: ‘You can go to prison for that sort of thing.’

Back at their hideout, Leatherslade Farm, the 15 robbers counted the money – mostly £1 and £5 notes, which is why it weighed 2.5 tons. When they reached £1 million, everyone paused to savour the sight. Charlie Wilson danced around singing ‘I Like It’ by Gerry and the Pacemakers. Some gang members played Monopoly with the cash. But their leader, Bruce Reynolds, felt a deep ‘emptiness’. Truly it is better to travel than to arrive, though the Royal Mail probably felt differently about their train.

A shopkeeper in nearby Brill displayed a notice saying ‘old banknotes accepted’. In 1965, with some robbers still on the run, PM Harold Wilson hatched a plan to render their haul worthless by reissuing every banknote in Britain. (Officials persuaded him this was impractical.) Long before then, though, many of the gang had been caught. Underworld gossip provided early leads; further clues came with the discovery of Leatherslade. Among the items left behind was a tea strainer, which made police suspect a woman’s involvement (‘Few men would think of such a thing’). But soon they were aided by fingerprints on a ketchup bottle and – oops! – the Monopoly board.

It’s now commonly accepted that three members of the gang remained unconvicted due to lack of evidence. For most of the robbers, however, the tale ended badly. Ronnie Biggs became a celebrity after escaping from Wandsworth prison (his training as a builder helping him to estimate the height of the wall from the number of bricks). But on his return from Rio four decades later, he was made to serve a further eight years.

Perhaps the saddest story was that of Buster Edwards (played on screen by Phil Collins), who ended up running a flower stall outside Waterloo station, before committing suicide in 1994. Two of the wreaths at his funeral were in the shape of trains.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in