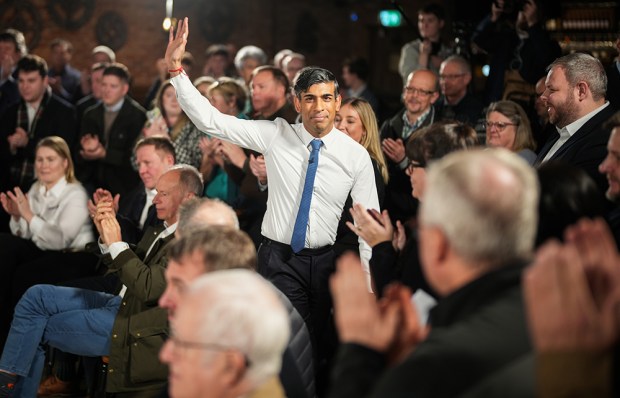

Last summer, all the Tory party could talk about was tax. It was at the heart of the leadership contest and the dividing line between Liz Truss and Rishi Sunak. The then foreign secretary promised to move fast and bring in deficit-financed tax cuts; the former chancellor said this would end in tears and instead pledged fully funded cuts over six years.

Neither plan saw the light of day. All talk of tax cuts was suspended after Truss’s mini-Budget, when the premise of her borrow-and-spend agenda was tested to destruction. Since then, tax has become a difficult topic to bring up. Even within Tory circles, calls to cut tax are usually met with a pointed question: did you forget what happened last time?

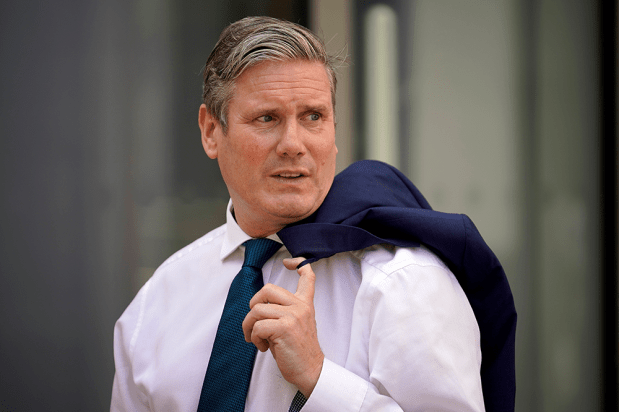

As a result, the Conservative party is heading towards a general election with the tax burden almost at its highest point in post-war history. ‘There was a gaping hole in the Prime Minister’s promises at the start of the year,’ laments a former minister. ‘Sunak promised to tackle inflation, he promised growth. He said nothing about taxes. You could forgive our voters for thinking we’ve forgotten what a burden we’ve put on their shoulders.’

Sunak’s supporters insist that he is a low-tax Tory who knows his party needs a compelling offer going into the next election. ‘All the difficult things we’re doing to get inflation down are so that we can then cut tax,’ says one government insider. ‘The cuts will be sustainable this time,’ they insist. But it is still unclear which taxes would fall and by how much.

‘I want to take an axe to inheritance tax,’ says one Tory MP, ‘but is that an election winner?’ Scrapping the much-loathed ‘death tax’ is an idea that has been discussed a lot over the past month. It was brought to the forefront once again this week, after it was revealed that four times as many people will be dragged into paying inheritance tax as was originally expected last year. Just 5 per cent of UK estates pay the levy, but inheritance tax is still considered one of the ‘most unfair’ taxes by the public. This is, after all, money that has already been taxed. What is the justification for taxing it again?

Another argument for cutting inheritance tax comes from inside the Treasury, which thinks it would be a less inflationary policy than an income tax cut. Inheritance is likely to be used to pay down mortgages or grandchildren’s student debt. An income tax cut (so the theory goes) would restore a small amount of spending power to every worker. But whether the inflation rate would really jump up due to a small sprinkling of tax relief is a disputed point, even within the party.

The real appeal of an inheritance tax cut is, as one MP puts it, that ‘Rachel Reeves won’t copy it’. Sunak’s latest strategy is to try to show the differences between the Tories and Labour. So far, it has amounted to announcements over energy policy but many of the Prime Minister’s colleagues would like to see him do the same with tax.

‘The politics of inheritance tax could be quite significant, if it creates a clear dividing line between us and Labour,’ says a minister. ‘But that doesn’t make it the right tax to cut, when you’ve got Middle England caught up in a current of fiscal drag.’ Millions are being hit by freezes to tax thresholds. Inflation means that two million more people will be pulled into the higher tax bracket over the next five years. Around three million more low-paid workers will end up paying income tax on what little they earn, because the personal allowance has been frozen at £12,570.

When George Osborne was in the Treasury, the coalition government worked to take lower earners out of the income tax bracket altogether. It helped the party win an unexpected majority in 2015. Tax relief for lower earners is seen as an alternative electoral offer to cutting inheritance tax (currently there is little optimism that money can be found for both). This is what the government must weigh up: a policy that generates headlines, such as cutting inheritance tax, versus one that is more widely felt, such as taking a penny off income tax.

The markets are still anxious about Britain borrowing money: the UK now pays more than any other major country to do so. At 4.4 per cent, Britain’s rate is higher than Italy’s. And while predictions about where interest rates will peak have fallen in recent weeks, the base rate is still far higher than some of Sunak’s supporters had hoped it would be by this point. ‘Things look better than they did four weeks ago,’ says one government insider, ‘but not four months ago.’ Immediate tax cuts, then, will need to be financed by restraint on spending.

This is the conversation the Tory party did not want to have last summer. But the Treasury is forcing it now, asking ministers what savings can be found in their departments. Secretaries of state are supposed to be using this month to work out where money can be found for tax cuts next year. Special attention is being paid to the Department for Work and Pensions, which has budgeted for a massive increase in long-term sickness benefits. There are now 4,000 claims a day – twice the pre-pandemic rate. Welfare spending will be a particular focus, not least because there are more than a million job vacancies to be filled. Getting people back into work will have to be the main priority.

Then comes the price tag attached to ending the strikes: some £5 billion in public sector pay raises. Given that welfare and pensions have risen in line with inflation, questions are being asked about how restrained the government can be. ‘Do we have the guts to look at means-testing for pension benefits, or to reduce the pensions triple-lock to a double-lock?’ asks a minister. ‘If we want to cut taxes, at some point we have to talk about the size of the state.’ As chancellor, Rishi Sunak used to say precisely the same. As Prime Minister, he has discovered how hard it is to stop spending money.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in