In 1957, when my dear godmother, the Marchioness of Dufferin and Ava (1941-2020), was 16, she began her diary. The granddaughter of the Duke of Rutland and daughter of Loel Guinness, an MP, financier and Battle of Britain pilot, Lindy Dufferin had a gilded childhood. Her entries as a teen are like no other: ‘Randolph Churchill [Winston’s son] was staying the night here… It was most embarrassing because Randolph was very drunk…’ In October 1957, she was in Paris: ‘The Dutchess [sic] of Windsor came… I did a show of Rock & Roll. It was all great fun. Bon Soir!’

But, amid all the luxury, a note of seriousness enters – there was art, too.

That autumn, she went to stay with her mother in Coughton, Warwickshire. There the artist Paul Maze (1887-1979), an Anglo-French painter known as ‘the last of the post-impressionists’, came to stay. He did a drawing for teenage Lindy of his house in Twyford, which she stuck into her diary. It was the first of many great artists she and her husband, the Marquess of Dufferin and Ava, would collect over the years. So began Lindy’s unique life as art collector, artist, patron and entrepreneur.

Sheridan Dufferin set up the Kasmin Gallery with John Kasmin in New Bond Street, where they held the first David Hockney show in 1963. Hockney painted and drew Lindy and Sheridan several times. Hockney’s most famous painting, ‘A Bigger Splash’, hung in the Dufferins’ London house. ‘It had been bought by Sheridan when the film director Tony Richardson turned it down,’ Hockney tells me. ‘[Richardson] had had it delivered to his house on Egerton Crescent, kept it for a week and then decided he hated Hollywood. Lindy knew it wasn’t about Hollywood at all. The painting cost them £800. They owned it for many years and when Sheridan died, it went to the Tate.’

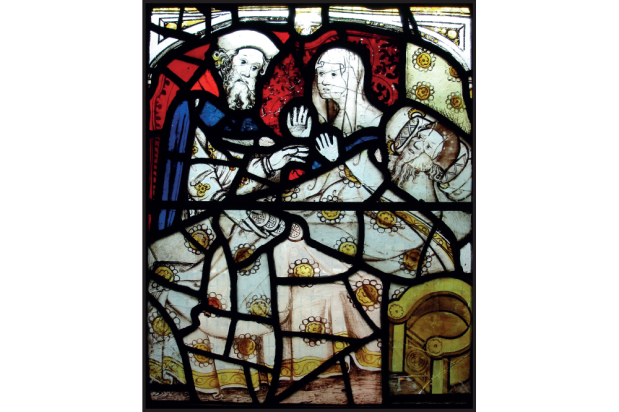

Lindy was a considerable painter in her own right. She was taught by Oskar Kokoschka and Sir William Coldstream. In more than 20 shows, in London, Dublin, Paris and New York, she developed a broad range of styles, from realist to cubist to abstract. Her greatest influence was the Bloomsbury artist Duncan Grant, whom she met in 1958. She was 17; Grant was 74. She learned from him at Charleston, the Bloomsbury epicentre in Sussex, for the following decade. At Clandeboye, the Dufferins’ ancestral home near Belfast, Lindy created the Duncan Grant room, filled with her collection of his paintings, his portrait of her and hers of him.

‘She loved telling the story of their meeting as a “coming home” and of finding her father figure,’ says Catherine Goodman, artistic director of the Royal Drawing School in London. ‘She was deeply connected, through her love of the natural world, to the English/Irish Romantic tradition of landscape painting. Jack Yeats, William Blake, William Nicholson, Ivon Hitchens and John Craxton were her touchstones.’

The Dufferins collected all those painters and more, including Lucian Freud, once married to Sheridan’s sister, the novelist Lady Caroline Blackwood. Sheridan, conscious of the memory of his ancestor, the 1st Marquess of Dufferin and Ava, Viceroy of India, collected 19th-century Indian Company paintings.

And, all the while, she developed her own painting style, particularly when it came to depicting her champion cows. Her friend Tom Stoppard says: ‘I caught her at the best moment in her cubist cow movement before she took it too far!’

Clandeboye became a kernel of art, literature and music. Vikram Seth came to stay. Robert Lowell gave a recital. She set up the Clandeboye Music Festival with Barry Douglas, one of Britain’s great pianists. It will take place this month. And Van Morrison regularly came over to Clandeboye from his home in nearby Cultra. ‘There was often a gathering with a few people at Clandeboye,’ says Sir Van. ‘We did some songs. Hannah Rothschild [the writer and daughter of Lord Rothschild] was here singing some back-up. She was pretty good.

‘Lindy was kind enough to let me use the Banqueting Hall for rehearsals and recordings. We recorded several things there – it’s got good acoustics. And I had three birthday parties there.’

What a restless, questing mind my godmother had – and what a place she and Sheridan occupied in the art world for 60 years. As Stoppard put it, ‘She had no neutral gear.’

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in