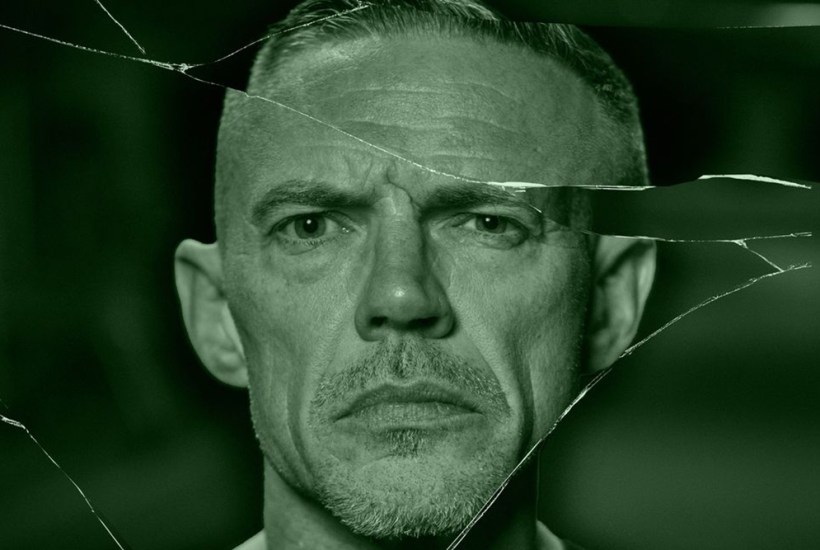

There should really be a special word for it: that vicarious fragility you feel when hearing of a minor decision with catastrophically heavy consequences, as if a falling acorn had tipped a boulder. In the case of John O’Hegarty, the subject of the engrossing podcast I’m Not Here To Hurt You, the catalyst for disaster was a quick short cut the wrong way down a one-way Dublin street while working as a bicycle courier. It would ultimately lead him – an academic with a master’s degree in psychology – into heroin and crack cocaine addiction, followed by a stint as a bank robber and eight years in prison.

The trouble was, that reckless turn in 2002 led him to collide with a pedestrian, a 56-year-old auctioneer called Roger Handy – who then fell, hit his head and later died in hospital, leaving a devastated family. ‘I can still feel the impact,’ O’Hegarty says of the crash: in this story the literal frequently blurs into the metaphorical. Racked with guilt, he was soon in the eye of a media storm, his identity recast in headlines as ‘The Killer Courier’. It took its toll: ‘Not long after, I embarked upon quite a distinct course of self-destruction.’

O’Hegarty is frank, likeable and eloquent, with the almost weary clarity that comes from having survived his own worst judgments, and those which others cast upon him. Given these qualities, the potential danger for any podcast is that his viewpoint will easily dominate the narrative, while those of the people most affected by his actions go unheard. Alert to this, the host Kevin Doyle – an Irish Independent journalist – makes creditable efforts to widen and interrogate O’Hegarty’s account, which nonetheless emerges as broadly accurate. The podcast team even seeks out the late Mr Handy’s business partner, who recalled O’Hegarty remaining with Handy after the crash: ‘I thought he was a nice kid. He could have fecked off.’

O’Hegarty’s subsequent slide into addiction and crime was occasioned not by too little feeling, it seems, but an unbearable excess of it. Drugs briefly numbed the pain, but a crack cocaine habit guzzles money. To fund it, he embarked on a new career as ‘Ireland’s most polite bank robber’. With a pretend gun from Smyths toy store, a cap with a fake ponytail, a velcroed uniform that could be speedily removed and a note that said ‘I am not here to hurt you or anyone else’, he was ready to go. Hold on – despite the reassuring note, thinking a gun was pointed at them must have terrified the bank tellers, mustn’t it? asked Doyle. ‘Yes,’ admits O’Hegarty flatly. ‘It scared the living shite out of them to be honest.’ He did 16 robberies in all before being caught. Released on bail, he did it again.

The detail of the robberies is gripping; they were tightly handled yet increasingly courting capture. It feels as if O’Hegarty ultimately accepted prison – walked towards it, even – as a means of doing extended penance for that first wrong turn. Today he has little interest in justifying his actions, only in explaining them. On the day of the cycle crash, he said, a fissure opened up in his world: ‘That crack emerged and I just floated away.’ Crack as in the fracture, or the drug? You can lose sight of yourself in both.

Culpability on a very different scale is the subject of Tortoise Media’s thoughtful Genocide hunters: on the trail of a mass murderer. As the host Will Brown observes, we seem to live in an ‘age of impunity, where the bad guys keep getting away’. But accountability resurfaced this year in a South African courthouse with the appearance of Fulgence Kayishema, a former police chief long wanted for his role in the Rwandan genocide.

A window on his past is provided by a chilling interview with Safari Jean Bosco, a Tutsi former neighbour who witnessed Kayishema and other Hutu extremists attacking Nyange church in 1994. More than 2,000 Tutsis had sheltered there, mainly women and children seeking protection. They met with a massacre instead; Bosco only survived by hiding in a pile of Tutsi corpses. He remembered Kayishema as a Hutu bigot, a teacher-turned-police inspector who once scolded some Hutu cattle thieves that instead of robbing Tutsis it would be better to kill them, after which ‘their cattle would have been yours anyway’.

Now Brown observes Kayishema in the dock nearly 30 years later, a large man with ‘an almost Mona Lisa smile on his face’, employed as a security guard for an unwitting white family who thought highly of him. His grotesque secret had lain concealed for decades beneath multiple identities and false documents, protected by the silence of elements in the Rwandan diaspora; it also eluded the frantic efforts of ‘former cops, spooks and private investigators’ who sought the $5 million US bounty for his capture.

In the end a small, dedicated team of UN investigators tracked him down. It’s a feverish, messy route to retribution, and Brown untangles it expertly. Still, it’s good to know that, against the odds, the long arm of justice can occasionally flex a muscle.

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

You might disagree with half of it, but you’ll enjoy reading all of it. Try your first month for free, then just $2 a week for the remainder of your first year.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in