Michael Jordan famously said ‘Republicans buy sneakers too,’ when declining to back a progressive politician. These sage words echo throughout the corporate world. Customers have many different political and social beliefs. Some are conservative. Some are progressive. Some just want to buy shoes.

Companies sometimes risk forgetting this, entering into partisan political debates. Companies have donated millions to the “yes” campaign for the Voice Referendum. But should they enter the debate at all?

Let’s be clear about how the donations operate and who is paying: While the donation is coming from the company, the decision maker is the CEO. And the CEO is spending shareholders’ money on donations, getting the dopamine hit of perceived altruism, while spending little if any of their own cash.

The companies’ donations are interesting given that the Voice is partisan, with the Labor and Liberal parties being at cross-purposes. Public support also remains tight. Some polls suggest that public support has dipped into negative territory.

This creates a conundrum for corporations. On the one hand, public support for the Voice seems thin on the ground. And the public is bitterly divided. On the other hand, “yes” campaigners assert that ‘silence is political,’ implying that neutrality is not an option, seeming to be wedging corporations.

This is an important issue regardless of your position on the Voice. You might support the Voice. But what about the next cause that companies pursue? Let’s explore this further.

What, then, are corporations to do?

Managers are in a tough spot. They might well be unsure about whether they should engage with the Voice referendum, feeling pulled in multiple directions.

The basic answer lies in The Corporations Act. Corporations Act Section 181 states that the CEO and its board must exercise their powers “in good faith in the best interests of the corporation” and “for a proper purpose.” What does this mean?

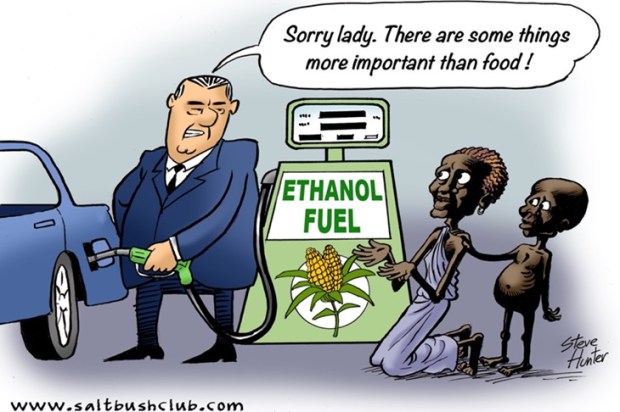

The operative obligation is to act “in the best interests of the corporation.” This is usually taken to mean maximizing shareholder wealth. And there are strong reasons for this. In 1989, the Standing Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs considered social and environmental factors, suggesting that they are relevant if they can influence corporate performance. However, notably, the subsequent legislation made no reference to environmental considerations. Similarly, whereas the equivalent New Zealand law makes reference to employees’ interests, the subsequent Australian law does not.

Australia’s Corporations and Markets Advisory Committee (CAMAC) even explicitly considered whether to amend directors’ duties to encompass social matters. However, they specifically noted that this would create uncertainty and could undermine managers’ accountability to their own employers: their shareholders. It is abundantly clear, therefore, that officers and directors must act in their shareholders’ best interests.

Officers and directors are not at liberty to pursue extraneous social causes that do not benefit corporations. Indeed, the academic literature highlights that such activities undermine shareholder wealth and create ‘agency conflicts’ owing to managers pursuing pet projects using other peoples’ money.

The sense of ‘altruism’ in donations might make managers feel morally justified in ignoring their own obligations. This has been documented anecdotally, with instances such as Sam Bankman-Fried. Academic research shows that individuals ‘cheat more’ when they can feel altruistic or morally justified about doing so. Thus, managers might be tempted to use shareholders’ money to support a cause that they believe is moral, ethical, or righteous, even if this is inconsistent with directors’ duties. It should be noted, however, one of the authors is under a cloud of suspicion.

To be clear, it is extremely unlikely that any shareholder will sue over corporate donations. It is not worth the legal fees and the risks inherent in litigating a nascent area. But, if managers genuinely want to be ethical, they should start by complying with their obligations to their own shareholders.

Does engaging with the Voice referendum increase shareholder wealth? This brings us back to the voice. Managers must ask themselves: is there a business case for getting involved? That is, does donating the money in this way benefit shareholders?

The answer is not straightforward and must depend on the company’s own circumstances. It is too easy to use the adage “Go woke, go broke.” But, the business case for engagement is not strong.

The company must consider myriad factors, including: (a) How will their stance impact employee loyalty and productivity, if at all? (b) What will customers and suppliers think? (c) What will regulators think, and how will this impact interactions with the government?

The government might respond negatively – possibly punitively – if a corporation deviates from its preferred narrative. This might be a subconscious and biased belief that disagreement signals incompetence. It might also be very conscious, as is implicit in the proposed ACMA powers on misinformation: The clear concern is that if the government disagrees with you, perhaps they will deem your stance to be misinformation and seek to silence it.

But do we really want to live in a world where the government can coerce silence through implicit threats of retribution? Corporations, too, risk setting a negative precedent by kowtowing to the government in this manner. For example, the corporation might regard complicity as costless this time. But what if it is about fiscal policy, mining rights, energy policy, or climate policy? Corporations must be conscious about the signal they send in future interactions and about letting the government believe it can bully corporations. Is that a long-term winning strategy?

The Voice also likely has a non-positive impact on corporations. The Voice would have the power to engage with, access, and thus, influence myriad government bodies. This includes bodies concerning climate change, agriculture, and monetary policy. Those bodies can ignore The Voice’s representations. But what if they never heard counter-representations or counter-arguments? In that case, it might be akin to a court only hearing one side of the case. Regardless, The Voice is not established to have special expertise in monetary policy, for example. Therefore, it is not clear that The Voice would improve decision-making. Perhaps the ALP will reveal policy details that would make that obvious. At present, it has not done so. This creates greater corporate risk.

The situation with customers and employees is not obvious. If indeed fewer than 50% of Australians support The Voice and “no” supporters are more resolute than are “yes” supporters, then it is not clear that placating “yes” supporters – at the risk of losing “no” supporters – is strategic. If the majority of your customers and employees disagree with your stance, is pushing that stance good for the bottom line? Similarly, if a large minority of your customers support “yes,” it might be unwise to take any position.

This is the case even if the customers and employees are indifferent to the company’s political stance. Suppose customers and employees simply do not care, then it is not clear how donations would increase corporate revenue. But they would increase costs. This would harm profitability. But, managers do not pay the price. Rather, this implicitly comes out of shareholders’ pockets.

We could argue for a small exception where the cause is clear human rights import. In many cases, human rights violations are already illegal. But corporations should avoid these in any case. They should avoid industrial disasters, slave-like conditions, and other abuses. Corporations should avoid racist policies that give especial power, money, and access to people on the basis of race. These should be clear norms.

Where does this leave companies? Corporations are thus on shaky ground when they support The Voice. The business case seems unclear. The issue is partisan, and people are bitterly divided. It is not clear that taking a side at this point will benefit the bottom line and could risk alienating customers and employees. Perhaps companies could save money and invest it. Or spend the money on bonuses to incentivise employees. Or distribute it to shareholders. The old adage ‘Republicans buy sneakers too’ is as true now as it ever was.

Mark Humphery-Jenner is an Associate Professor of Finance at UNSW Business School

Got something to add? Join the discussion and comment below.

Get 10 issues for just $10

Subscribe to The Spectator Australia today for the next 10 magazine issues, plus full online access, for just $10.

Comments

Don't miss out

Join the conversation with other Spectator Australia readers. Subscribe to leave a comment.

SUBSCRIBEAlready a subscriber? Log in